[島の男]

The Aran Islands

Part Ⅲ

by J. M. Synge

With drawings by Jack B. Yeats

Dublin, Maunsel & Co., Ltd.

[1907]

アラン島

第三部

ジョン・ミリングトン・シング著

ウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツ挿絵

ダブリン マウンセル社刊

姉崎正見訳

附 やぶちゃん注

[島の男]

The Aran Islands

Part Ⅲ

by J. M. Synge

With drawings by Jack B. Yeats

Dublin, Maunsel & Co., Ltd.

[1907]

アラン島

第三部

ジョン・ミリングトン・シング著

ウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツ挿絵

ダブリン マウンセル社刊

姉崎正見訳

附 やぶちゃん注

[やぶちゃん注:本頁は私のブログでの第三部の公開を経て、第三部全文を一括して作成したものである。底本・凡例及び解説は第一部を参照されたい。今回、明らかな脱字と思われる箇所には【 】で字を補った。――これを私と同じく母を失う聖痕(スティグマ)を受けた教え子T.S.君に捧げる――【2011年3月25日】]

第 三 部

私がパリーに居る間、マイケルから一本の手紙が來た。それは英語であつた。

親愛なる友よ、――此の前、手紙を戴いてから、あなたは御丈夫なことと思ひます。あれ以來何度もあなたのことを思ひます。また將來もあなたのことを忘れないでせう。

私は三月初めに二週間ばかり家に籠つてゐました。インフルエンザで大へん惡かつたのでしたが、隨分養生をしました。

今年の初めから、私はよい賃銀を取るやうになりました。辛くはないのですが、やつて行けるかどうか案ぜられます。私は木挽工場で働いてゐるので、木材を賣つて金を儲けたり、その帳付けをしたりしてゐます。

一週間に二三囘、家から手紙やらニュースやらを貰つてゐます。皆無事です。またあなたの島のお友達の事を云へば、皆同じく無事です。

あなたはダブリンで私の友達の何何さんや、その他これ等紳士淑女の誰かにお逢ひになりましたか?

私は間もなくアメリカへ行かうと思ひますが、私が無事なら來年までは待たないでせう。

お互ひに丈夫で機嫌よく再びお逢ひ出來る事を望んでゐます。

も早、お別れを言ふところに來ました。さよなら。ですが、永久にではなく。早く返事を下さい。――ゴルウェーの友より。

返事を何卒早く。

もう一つの手紙の方は、やや飾つた心持である。

親愛なるS樣、――私は前ら寸暇を得て、一筆さし上げようと思つてゐました。

先日、お手紙を戴いてから、あなたは至極健在でいらつしやる事と思ひます。

今あなたは生れ故郷の言葉を習ひに、此處へ來る時期が來たやうに思はれます。二週間前、此の島に盛んなフェス[愛蘭土の昔よりの祭で、此の日は演劇、音楽ダンス等が行はれる]がありました。南島から非常に澤山の參集者がありましたが、北島からはさう多くはありませんでした。

私の従兄弟二人が此の家に三週間或はそれ以上ゐましたが、今は歸りました。それで、若しあなたがいらつしやるなら場所があります。いらつしやる前に手紙を下さい。私たちは一つ骨折つて、出來るだけ面倒をみませう。

私は今、二ケ月ばかり家にゐます。働いてゐた工場が燒けましたから。その後、ダブリンに行きましたが、比の都會は私の健康によくありませんでした。――敬愛する貴方の友より。

此の手紙を受けて直ぐ、私はマイケルに、そちらへ戻るつもりだと云ふ手紙を出した。今度、私は船が直接に中の島へ行く日を選んだ。船卸臺の外側に二列に竝で待つてゐるカラハの間へ舟が進んで行くと、私はマイケルがまたも島の着物を着て、カラハの一つを漕いでゐるのを見かけた。

彼は認めた合圖はしなかつたが、船に横付けになると直ぐに、甲板に攀ぢ上つて來て、私の居る船橋までまっしぐらにやつて來た。

「ヴ・フイル・テゥ・ゴ・モイ?(御機嫌如何です?)」彼は云つた。「貴方の荷物は何處ですか?」

彼のカラハは汽船の船首に近い惡い場所にかかつてゐたので、カラハが船側にあたつて搖れたり傾いたりするなかを、私は小麥の袋や自分の鞄の上の可成り高い所から吊り下ろされた。

本船から離れると、マイケルに手紙を受取つたかどうかを聞いた。

「いいえ」彼は云つた。「影も形も見ません。ですが、大概來週屆くでせう。」

船卸臺の一部が冬の間に、流されてしまつたので、私たちはその左側の方の岩の中へ、歸つて來つつある他のカラハと共に順を待つて、上陸しなければならなかつた。

上陸すると直ぐに人人が歡迎の挨拶を云ひに集まつて來て、私を取り圍んだ。握手をしながら、此の冬遠くへ旅行して、澤山の不思議を見なかつたかと尋ねた。そして終りには例の如く今、世界では大きな戰爭があるかと聞いた。

此の人たちのゲール語の挨拶を聞き、此の人たちの中に私を一人殘して汽船の出て行くのを見ると、私は嬉しさに戰くのを覺えた。その日は天氣がよく、空は澄み、海は石灰岩の向うに輝いてゐた。遙かに大島の斷崖やコンノートの山山のうすい霧はまだ夏の如き幻想を私に起させた。

一人の小さな男の子が私の來たことをお婆さんに知らせに遣らされた。私たちは話しながら、その後を鞄を持つてついて行つた。

私の方の土産話がすつかりなくなると、彼等は自分の方のを語り出した。此の夏、澤山の――四五人の――外國人が、その中には一人のフランスの僧侶も交つて、此の島にゐたこと、馬鈴薯は出來が惡かつたが、ライ麥は日照の來る一週間の前までは、出來がよくなりかけてゐたこと、それから、燕麥に變つたことなどを語つた。

「お前さんが、若し私たちの事をよく知らないなら、」語り手の一人の男が云つた。「私たちは嘘を云つてゐると思ふだらうが、毛頭噓ぢやない。それはずんずん伸びた。さうだ、膝ぐらゐの高さになつたね。それから燕麥になつた。そんなやうな事はウィクロー郡では見かけなかつたかね?」

宿では何もかも、もとのままであつた。お婆さんの機嫌と滿足はマイケルのゐるために、もと通りになつてゐた。私は椅子に腰を下し、炭火の端でパイプに火をつけながら、また來てよかつたと、嬉しさに聲を立てんばかりであつた。

*

Part III

LETTER HAS come from Michael while I am in Paris. It is in English.

MY DEAR FRIEND,--I hope that you are in good health since I have heard from you before, its many a time I do think of you since and it was not forgetting you I was for the future.

I was at home in the beginning of March for a fortnight and was very bad with the Influence, but I took good care of myself.

I am getting good wages from the first of this year, and I am afraid I won't be able to stand with it, although it is not hard, I am working in a saw-mills and getting the money for the wood and keeping an account of it.

I am getting a letter and some news from home two or three times a week, and they are all well in health, and your friends in the island as well as if I mentioned them.

Did you see any of my friends in Dublin Mr.--or any of those gentlemen or gentlewomen.

I think I soon try America but not until next year if I am alive.

I hope we might meet again in good and pleasant health.

It is now time to come to a conclusion, good-bye and not for ever, write soon--I am your friend in Galway.

Write soon dear friend.

Another letter in a more rhetorical mood.

MY DEAR MR. S.,--I am for a long time trying to spare a little time for to write a few words to you.

Hoping that you are still considering good and pleasant health since I got a letter from you before.

I see now that your time is coming round to come to this place to learn your native language. There was a great Feis in this island two weeks ago, and there was a very large attendance from the South island, and not very many from the North.

Two cousins of my own have been in this house for three weeks or beyond it, but now they are gone, and there is a place for you if you wish to come, and you can write before you and we'll try and manage you as well as we can.

I am at home now for about two months, for the mill was burnt where I was at work. After that I was in Dublin, but I did not get my health in that city.--Mise le mor mheas ort a chara.

Soon after I received this letter I wrote to Michael to say that I was going back to them. This time I chose a day when the steamer went direct to the middle island, and as we came up between the two lines of curaghs that were waiting outside the slip, I saw Michael, dressed once more in his island clothes, rowing in one of them.

He made no sign of recognition, but as soon as they could get alongside he clambered on board and came straight up on the bridge to where I was.

'Bh-fuil tu go maith?' ('Are you well?') he said. 'Where is your bag?'

His curagh had got a bad place near the bow of the steamer, so I was slung down from a considerable height on top of some sacks of flour and my own bag, while the curagh swayed and battered itself against the side.

When we were clear I asked Michael if he had got my letter.

'Ah no,' he said, 'not a sight of it, but maybe it will come next week.'

Part of the slip had been washed away during the winter, so we had to land to the left of it, among the rocks, taking our turn with the other curaghs that were coming in.

As soon as I was on shore the men crowded round me to bid me welcome, asking me as they shook hands if I had travelled far in the winter, and seen many wonders, ending, as usual, with the inquiry if there was much war at present in the world.

It gave me a thrill of delight to hear their Gaelic blessings, and to see the steamer moving away, leaving me quite alone among them. The day was fine with a clear sky, and the sea was glittering beyond the limestone. Further off a light haze on the cliffs of the larger island, and on the Connaught hills, gave me the illusion that it was still summer.

A little boy was sent off to tell the old woman that I was coming, and we followed slowly, talking and carrying the baggage.

When I had exhausted my news they told me theirs. A power of strangers--four or five--a French priest among them, had been on the island in the summer; the potatoes were bad, but the rye had begun well, till a dry week came and then it had turned into oats.

'If you didn't know us so well,' said the man who was talking, 'you'd think it was a lie we were telling, but the sorrow a lie is in it. It grew straight and well till it was high as your knee, then it turned into oats. Did ever you see the like of that in County Wicklow?'

In the cottage everything was as usual, but Michael's presence has brought back the old woman's humour and contentment. As I sat down on my stool and lit my pipe with the corner of a sod, I could have cried out with the feeling of festivity that this return procured me.

[やぶちゃん注:栩木伸明氏訳2005年みすず書房刊の「アラン島」の「あとがき」によれば、シングの三度目のアラン訪問は1900年9月15日から10月14日である。

「フェス[愛蘭土の昔よりの祭で、此の日は演劇、音楽ダンス等が行はれる]」原文“a great Feis”。ゲール語の発音は「フェシュ」に近い。伝統的なゲール語の総合文化祭で、姉崎氏の注にあるように、ダンス・コンテストをメインとして、音楽・演劇などの芸術祭と各種スポーツなどの競技が行われる。英語のウィキを見る限りでは、開催日は限定されていないようである。現在、恐らくこの祭典から生まれたものとして、アイルランド最大の芸術祭としてヨーロッパでも有名なゴールウェイ芸術祭(“The

Galway Arts Festival”・ゲール語“Féile Ealaíon na Gaillimhe”)が毎年七月に行われているが、これは1978年に始まる新しいもので、七月では投函されたであろうマイケルの手紙の日時ともずれるように思われる。

「――敬愛する貴方の友より。」原文はゲール語で“--Mise le mor mheas ort a chara.”。栩木氏は「ミシヤ・ラ・モール・ヴアス・オルト・ア・ハラ」のルビを振られている(拗音はルビのため確認出来ないので、そのまま写した)。

「ヴ・フイル・テゥ・ゴ・モイ?(御機嫌如何です?)」“Bh-fuil tu go maith?”。栩木氏の音写は「ヴィル・トゥー・ゴ・マイ」とされている。

「ライ麥は日照の來る一週間の前までは、出來がよくなりかけてゐたこと、それから、燕麥に變つた」とあるが、勿論、イネ科ライムギ Secale cereale がイネ科カラスムギ属エンバク Avena sativa になることはあり得ない。彼らには失礼だが、エンバクは元来、ライムギ栽培時の雑草であったから、普段よりも伸びの早かったエンバクを希望的にライムギと誤認したものか?

「世界では大きな戰爭があるか」1900年当時は6月21日、義和団の乱が発生、清がイギリス・アメリカ・ロシア・フランス・ドイツ・オーストリア=ハンガリー・イタリアの八ヶ国に宣戦布告、シングがアランに帰る直前の8月14日に連合軍は北京攻略を開始、翌日、北京は陥落した。義和団の鎮圧から北京議定書によって翌1901年9月7日に終結を見た。但し、アメリカに移住した親族が多いアランの人々にとっては、前年から燻っていた米比戦争(べいひせんそう 1899年~1913年:アメリカ合衆国とアメリカが併合しようとしたフィリピンとの間で勃発した戦争)の方が心痛の関心事であったと思われる。当時の戦況は既にアメリカに優位で対ゲリラ戦となっており、正にシングが島に着く直近、9月13日にはプラン・ルパの戦い、9月17日にもマビタクの戦いがあった。最終的にはフィリピン第一共和国が崩壊し、フィリピンは植民地化された。因みに、やはりシングが渡島する一週間前9月8日に一人の日本人が大日本帝国文部省留学生としてロンドンに向けて横浜を出航している。――夏目漱石、その人であった。]

今年はマイケルは晝間は忙しい。併し今は、秋の月があり、夜の大方を、灣の方を眺めながら島を歩き廻つて過した。灣には雲の蔭が、黒と金の面白い綾模樣を投げてゐた。今夜、村を通つて歸る途中、お祭り騒ぎが一軒の稍々小さな家から洩れて來た。マイケルに聞くと、若い男女が、一年中の此の頃に、遊戲をやつてゐるのださうであつた。私もその仲間入りをしたかつたが、彼等の娯みを邪魔しては惡いと思つた。道の兩側にちらほら家のかたまつてある處を再び通りながら、私がフランスやバヴァリヤ邊を旅行した時、夜、折折通つた處を憶ひ出した。其處は再び目醒めるとは思はれないまでに、靜かな蒼い夜の幕に包まれてゐた處であつた。

後で、私たちは砦の丘に登つた。マイケルは手の屆くほど近くに住みながら其處へ眞夜中に登つた事はなかつたさうである。その場所は、島の頂上に、先史時代の石は光茫のやうに浮き出して、その光の中に、思ひかけない壯觀を呈してゐた。私たちは幽かな黄色い屋根を見下し、又その向うにキラキラ輝いてゐる岩や靜かな灣を眺めながら、石垣の頂上を暫く彷徨つた。マイケルは四圍の自然の美を氣付いてをりながら、それを決して直接語らない。私たちは重に星や月の運行の事ばかりを長い間ゲール語で話しながら、多くの宵を散歩した。

*

This year Michael is busy in the daytime, but at present there is a harvest moon, and we spend most of the evening wandering about the island, looking out over the bay where the shadows of the clouds throw strange patterns of gold and black. As we were returning through the village this evening a tumult of revelry broke out from one of the smaller cottages, and Michael said it was the young boys and girls who have sport at this time of the year. I would have liked to join them, but feared to embarrass their amusement. When we passed on again the groups of scattered cottages on each side of the way reminded me of places I have sometimes passed when travelling at night in France or Bavaria, places that seemed so enshrined in the blue silence of night one could not believe they would reawaken.

Afterwards we went up on the Dun, where Michael said he had never been before after nightfall, though he lives within a stone's-throw. The place gains unexpected grandeur in this light, standing out like a corona of prehistoric stone upon the summit of the island. We walked round the top of the wall for some time looking down on the faint yellow roofs, with the rocks glittering beyond them, and the silence of the bay. Though Michael is sensible of the beauty of the nature round him, he never speaks of it directly, and many of our evening walks are occupied with long Gaelic discourses about the movements of the stars and moon.

[やぶちゃん注:「お祭り騒ぎ」原文は“a tumult of revelry”で、“tumult ”も“revelry”も騒ぎであるから、正に飲めや歌えのどんちゃん騒ぎという意味である。これは例えば現在、大西洋に近い西海岸の村“Lisdoonvarna”リスドゥーンバーナで行われてい“Matchmaking Festival”(マッチメイキング・フェスティバル:お見合い・縁結び祭り)と呼ばれているものと同類の祭りである。マッチメイキング・フェスティバルはアイルランド政府観光庁の記事によれば、毎年9月から6週間に渡って行われる。昼の各所でのダンスパーティーに始まり、ホテルやパブでの生演奏が朝まで賑わい、実際に仲人役がおり、国外の旅行者など多くの男女の仲を取り持つ。二百年も前からアイルランドに伝わる最も古形の伝統的な祭りの一つである、とある。恐らくこれはローマ神話のフローラ祭などに起源を持つ民間信仰で、若い男女が夕刻から森の中に入って日の出までそれぞれに二人で過し、翌朝、花輪などを作って帰って村を飾るという儀式で、その間は無礼講の野合が許された(アンドレイ・タルコフスキイの「アンドレイ・ルブリョフ」の中で美事な再現が行われている。必見!)。本邦でもこうした祭りはかつて普通に存在した。古くは陰暦九月一日に行われて八朔祭とも呼ばれ、夜、男女が神社の鎮守の森に集って自由に関係を持ったのである。万葉の「

此の人たちは自然と超自然の區別をつけない。

今日の午後――島の人達の間によく面白い話の交はされる日曜であつた――雨が降つたので、私は村人の中でも比較的進歩した人の多く集まる、學校の先生の茶の間へ行つた。私は彼等の漁業や耕作の風習はよく知らず、話を續けてゆけば、必ず私の云ふことが彼等にわからなくなる事柄に來るし、また寫眞の珍しさも段段とうすれて來たので、私が仲間入りをして彼等が期待してゐるらしい慰み事をするのが少しむづかしくなつた。今日は簡單な體操の藝當や手品師の奇術を見せたが、大いに喜ばれた。

「ねえ、もし、」終つた時、一人のお婆さんは云つた。「そんな事はその土地の魔術使から教はつたのかね?」

奇術の一つは、村の人が切つた紐を繫ぐやうに見せるのであつたが、完全に成功したと見えて、一人の男はそれを持つて一隅に行き、繫いだと見える所を手に赤い筋が出來るまで引張つてゐた。

それから私にそれを返した。

「おやおや、」と彼は云つた。「こんな不思議なことはまだ見た事がない。お前さんの繫いだ所は少し細くなつてゐるが、もと通り丈夫だ。」

若い方の幾人かの人は疑はしげに見えたが、ライ麥が燕麥になつたのを見た年取つた方の人達は魔術をあつさり信じてしまつて、「ドゥイネ・ウァソル」(旦那)は魔術使のやるやうな事が出來る譯だと別に驚いた樣子もなかつた。

私は此の人たちと交つてから、新らしい理念の理解されない所には、いつも奇蹟は澤山あると云ふ事を實感してゐる。此の群島だけでも、神祕の密使を立てるほど奇蹟は毎年隨分起る。ライ麥が燕麥になつたり、嵐が取立ての役人を近づかしめないやうに吹き起つたり、又離れ島に獨りゐる牝年が子を産んだりするやうな種類の事はあたりまへの事である。

不思議とは稀に起る出來事で、雷雨とか虹のやうなものであるが、異る所はそれよりも少し稀で珍しいと云ふことである。私が散歩してゐて、時時村人の誰かと言葉を交はすことがある。そんな時、ダブリンから新聞が來たと云ふと、彼等は私に聞く。――

「そして、近頃、一體何か非常な不思議がありますか?」

私の熟練の藝當が終つた時、島の最も若くて素早い者でも私のした事が出來ないのを知つて驚いた。教へようと、一生懸命に彼等の手足を引張りながら氣がついたが、その動作の樂で美しいのは、實際よりずつと身輕に思はせてゐるのであつた。あの斷崖の間や大西洋の中でカラハに乘つてゐる所は、輕さうで小さく見えても、私たちのやうに着物を着て普通の部屋で見ると、彼等の多くは身體がどつしりとして、力強さうに見える。

少したつと、流石に島の代表的の踊り手である一人の男は起ち上つて、鮭跳びをしたり ――顏を下にして平たく伏して宙に高く跳び上るのである――その他幾つかの非常に素早い藝當を

私の奇術の評判は島中に擴がつたので、今夜は此處の茶の間で又やらなければならなかつた。きつと此の藝當は此處、代代傳はり覺えられるに違ひない。島の人たちは物を云ひ表はすのに、比喩をあまり知らないから、外來者の目星しい何かを捉へて、後の話にそれを用ひる。

それで、最近數年間、立派な指環をはめてゐる人の事を云ふ時に、「あの人は、島のお客であつた、何何夫人のやうに美しい指環をはめてゐる」と云ふ。

*

These people make no distinction between the natural and the supernatural.

This afternoon--it was Sunday, when there is usually some interesting talk among the islanders--it rained, so I went into the schoolmaster's kitchen, which is a good deal frequented by the more advanced among the people. I know so little of their ways of fishing and farming that I do not find it easy to keep up our talk without reaching matters where they cannot follow me, and since the novelty of my photographs has passed off I have some difficulty in giving them the entertainment they seem to expect from my company. To-day I showed them some simple gymnastic feats and conjurer's tricks, which gave them great amusement.

'Tell us now,' said an old woman when I had finished, 'didn't you learn those things from the witches that do be out in the country?'

In one of the tricks I seemed to join a piece of string which was cut by the people, and the illusion was so complete that I saw one man going off with it into a corner and pulling at the apparent joining till he sank red furrows round his hands.

Then he brought it back to me.

'Bedad,' he said, 'this is the greatest wonder ever I seen. The cord is a taste thinner where you joined it but as strong as ever it was.'

A few of the younger men looked doubtful, but the older people, who have watched the rye turning into oats, seemed to accept the magic frankly, and did not show any surprise that 'a duine uasal' (a noble person) should be able to do like the witches.

My intercourse with these people has made me realise that miracles must abound wherever the new conception of law is not understood. On these islands alone miracles enough happen every year to equip a divine emissary Rye is turned into oats, storms are raised to keep evictors from the shore, cows that are isolated on lonely rocks bring forth calves, and other things of the same kind are common.

The wonder is a rare expected event, like the thunderstorm or the rainbow, except that it is a little rarer and a little more wonderful. Often, when I am walking and get into conversation with some of the people, and tell them that I have received a paper from Dublin, they ask me--'And is there any great wonder in the world at this time?'

When I had finished my feats of dexterity, I was surprised to find that none of the islanders, even the youngest and most agile, could do what I did. As I pulled their limbs about in my effort to teach them, I felt that the ease and beauty of their movements has made me think them lighter than they really are. Seen in their curaghs between these cliffs and the Atlantic, they appear lithe and small, but if they were dressed as we are and seen in an ordinary room, many of them would seem heavily and powerfully made.

One man, however, the champion dancer of the island, got up after a while and displayed the salmon leap--lying flat on his face and then springing up, horizontally, high in the air--and some other feats of extraordinary agility, but he is not young and we could not get him to dance.

In the evening I had to repeat my tricks here in the kitchen, for the fame of them had spread over the island.

No doubt these feats will be remembered here for generations. The people have so few images for description that they seize on anything that is remarkable in their visitors and use it afterwards in their talk.

For the last few years when they are speaking of any one with fine rings they say: 'She had beautiful rings on her fingers like Lady--,' a visitor to the island.

[やぶちゃん注:「ドゥイネ・ウァソル」(旦那)」“'a duine uasal' (a noble person)”。「一人の高潔なる御方」という尊敬を含んだ呼称。ネット上の発音サイトで聴いたものを音写すると「ドウィナ・ウォソル」と聴こえる。栩木氏は「ディニャ・ウァサル」(表記は「デイニヤ・ウアサル」)とルビを振られている。時に「ア」は発音しない(若しくは後の単語の発音に吸収される)のだろうか? 姉崎・栩木両氏とも、ない。識者の御教授を乞う。

「鮭跳び」原文“salmon leap”。サケが遡上する際のジャンピングに似ているからであろう。実は“sal-”は「跳びかかる」で、“salmon”は跳びかかる魚の意が語源らしい。

『それで、最近數年間、立派な指環をはめてゐる人の事を云ふ時に、「あの人は、島のお客であつた、何何夫人のやうに美しい指環をはめてゐる」と云ふ。』原文は“For the last few years when they are speaking of any one with fine rings they say: 'She had beautiful rings on her fingers like Lady--,' a visitor to the island.”。“a visitor to the island”は会話文の外に出ているから、『例えばこの数年の間、彼らが立派な指環を嵌めている誰彼について話す際には、「あの人は指に何何夫人みたような美しい指環をはめてるね、」と言うのだが――この「何々夫人」とは、その実、何年も前に島をちょいと訪れたお客の名に過ぎないのである――。』というニュアンスである。]

私は全く暗くなるまで波止場に腰掛けてゐた。私はイニシマーンの夜と、その夜が此の村の人たちに大がいの仕事を日が暮れてからするやうにさせてゐる影響が、やつとわかりかけて來た。

幾羽かのたいしやく鴫やその他の野鳥が、海草の中で笛を吹くやうに或は叫ぶやうに鳴くのや、波の低い音が聞こえるばかりである。九月特有の蒸し暑い夜で、海の燐光や雲の晴れ間に時時見える星のほかには何の明りもなかつた。

孤獨の感じが強かつた。私は自分で自分の身體を見ることも感じることもできなかつた。私は波の音、鳥の聲、海草の香を意識してゐる中にのみ自分が存在してゐるやうであつた。

家に歸らうとした時、砂山の中で氣が遠くなつてしまつた。ぬるぬるした海草の中や濕つて崩れかかつた壁の中を手探りしてゐると、夜は嫌に寒く、憂鬱になつて行くやうであつた。

少したつて、砂の上を何か動いて來る音がして、二つの黒い影が傍に現はれた。それは漁から歸りがけの二人の男であつた。私はその人達に話しかけたが、聞き覺えのある聲であつた。そして連れ立つて家に歸つた。

*

I have been down sitting on the pier till it was quite dark. I am only beginning to understand the nights of Inishmaan and the influence they have had in giving distinction to these men who do most of their work after nightfall.

I could hear nothing but a few curlews and other wild-fowl whistling and shrieking in the seaweed, and the low rustling of the waves. It was one of the dark sultry nights peculiar to September, with no light anywhere except the phosphorescence of the sea, and an occasional rift in the clouds that showed the stars behind them.

The sense of solitude was immense. I could not see or realise my own body, and I seemed to exist merely in my perception of the waves and of the crying birds, and of the smell of seaweed.

When I tried to come home I lost myself among the sandhills, and the night seemed to grow unutterably cold and dejected, as I groped among slimy masses of seaweed and wet crumbling walls.

After a while I heard a movement in the sand, and two grey shadows appeared beside me. They were two men who were going home from fishing. I spoke to them and knew their voices, and we went home together.

[やぶちゃん注:「たいしやく鴫」ダイシャクシギ。第二部参照。

「燐光」原文“phosphorescence”。月や星、その他の雲の反射光や人工光源によって海の表面が暗闇の中で青光りすることを言っているものと思われる。]

秋の季節には、ライ麥

一つの畑から、翌年の種を取るのに必要以上の麥は取れないほど、土地は甚だ瘦せてゐるので、ライ麥の植ゑ付は屋根葺に使ふ藁を取るためのみに行はれる。

穀草の山は麥

麥

麥

二三日前、島で最も綺麗な子供たちのゐる家へ行つたが、十四歳位の一番上の娘が出て來て、戸口の傍の積藁の上にどつかと坐つた。日光が彼女とライ麥の一所に當つて、彼女の姿や赤い着物は、その下の藁と共に網や雨合羽を背景とした面白い浮彫のやうであり、また自然に勝れた調和と色彩のある繪のやうであつた。

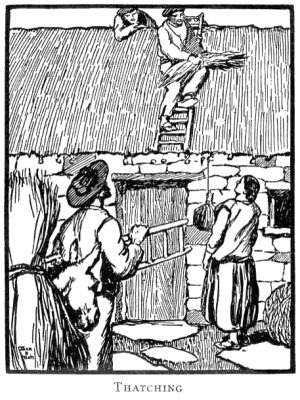

此の宿で、屋板葺――毎年爲される――が丁度行はれてゐる。繩綯ひは天氣の變り易い時、一方は小路で一方は茶の間で、行はれる。此の仕事には通常二人の男が一緒に坐り、一人は重い木の棒で藁を叩き、他は繩を造る。此の繩の重な部分は男の子或は女の子によつて、これに使ふために特別に作られた曲つた木片で綯はれる。

雨の日、屋内で仕事をしなければならない時は、繩を綯ふ人は段段と後退さりして、家の外へ出て、終には道を横切り或る時は一つ二つの畑を越える事もある。葺藁に密な網目を張るためには、各々が約五十ヤード位の非常に長い物を必要とする。村の家の半ばが此の仕事をしてゐる最中は、道は奇觀を呈する。綯はれつつある繩は、暗い戸口の何れかの側から出て、畑まで曲りくねつてゐる。人はその中を拾ひ歩んで行かなければならない。

大きな繩の玉が五つ六つ出來上ると、屋根葺の一隊が組織せられ、彼等は朝の夜明け前に、その家へやつて來る。そして仕事は普通その日のうちに終つてしまふほど、精出して初められる。

島に於いて共同してやる凡ての仕事と同じく、此の屋根葺も一種のお祭りと思はれてゐる。屋根に手がつけられた時から終りまで、どつと笑ふ聲、しやべる聲が續く。そして葺替へしてゐる家の主人は傭主ではなく、

此の宿の屋根が葺かれた日、大きなテーブルが私の部屋から茶の間の方へ持ち出され、御馳走付のお茶が二三時間毎に出された。道を通りがかつた人は多く茶の間へ立寄つて、しやべり聲は絶え間がなかつた。一度私が窓の處へ來た時、マイケルが破風の頂きから、私の天文學の講義の受け賣りをやつてゐるのを聞いた。併し彼等の話題は大概は島の事に關してゐた。

此の人達の智慧があり、愛嬌のあるのは、多く勞働の分離が無いためであるらしく、また從つて各人が多方面に發達するためでもあるらしい。各人のいろいろの知識や熟練には、可成り旺盛な精神力を必要とするからである。各自は二國語を使ふことが出來る。彼は熟練した漁夫で、なみはづれた度胸と機敏さを以つて、カラハを操る。彼は簡單な耕作を爲し、海草灰を焚き、革草鞋を拵へ、網を繕ひ、家を建て、屋取を葺き、また搖籠や棺桶を造ることが出來る。その仕事が四季と共に變はる。これは謂はば同じ仕事を常にしてゐる人にありがちな倦怠を防ぐことになる。海上生活の危險は彼に原始時代の狩人の機敏さを教へ、カラハに乘つて釣をして過す長い夜は、藝術を友として生活する人に獨特と思はれる或る感情を彼に植ゑ付ける。

*

[屋根葺き]

In the autumn season the threshing of the rye is one of the many tasks that fall to the men and boys. The sheaves are collected on a bare rock, and then each is beaten separately on a couple of stones placed on end one against the other. The land is so poor that a field hardly produces more grain than is needed for seed the following year, so the rye-growing is carried on merely for the straw, which is used for thatching.

The stooks are carried to and from the threshing fields, piled on donkeys that one meets everywhere at this season, with their black, unbridled heads just visible beneath a pinnacle of golden straw.

While the threshing is going on sons and daughters keep turning up with one thing and another till there is a little crowd on the rocks, and any one who is passing stops for an hour or two to talk on his way to the sea, so that, like the kelp-burning in the summer-time, this work is full of sociability.

When the threshing is over the straw is taken up to the cottages and piled up in an outhouse, or more often in a corner of the kitchen, where it brings a new liveliness of colour.

A few days ago when I was visiting a cottage where there are the most beautiful children on the island, the eldest daughter, a girl of about fourteen, went and sat down on a heap of straw by the doorway. A ray of sunlight fell on her and on a portion of the rye, giving her figure and red dress with the straw under it a curious relief against the nets and oilskins, and forming a natural picture of exquisite harmony and colour.

In our own cottage the thatching--it is done every year--has just been carried out. The rope-twisting was done partly in the lane, partly in the kitchen when the weather was uncertain. Two men usually sit together at this work, one of them hammering the straw with a heavy block of wood, the other forming the rope, the main body of which is twisted by a boy or girl with a bent stick specially formed for this employment.

In wet weather, when the work must be done indoors, the person who is twisting recedes gradually out of the door, across the lane, and sometimes across a field or two beyond it. A great length is needed to form the close network which is spread over the thatch, as each piece measures about fifty yards. When this work is in progress in half the cottages of the village, the road has a curious look, and one has to pick one's steps through a maze of twisting ropes that pass from the dark doorways on either side into the fields.

When four or five immense balls of rope have been completed, a thatching party is arranged, and before dawn some morning they come down to the house, and the work is taken in hand with such energy that it is usually ended within the day.

Like all work that is done in common on the island, the thatching is regarded as a sort of festival. From the moment a roof is taken in hand there is a whirl of laughter and talk till it is ended, and, as the man whose house is being covered is a host instead of an employer, he lays himself out to please the men who work with him.

The day our own house was thatched the large table was taken into the kitchen from my room, and high teas were given every few hours. Most of the people who came along the road turned down into the kitchen for a few minutes, and the talking was incessant. Once when I went into the window I heard Michael retailing my astronomical lectures from the apex of the gable, but usually their topics have to do with the affairs of the island.

It is likely that much of the intelligence and charm of these people is due to the absence of any division of labour, and to the correspondingly wide development of each individual, whose varied knowledge and skill necessitates a considerable activity of mind. Each man can speak two languages. He is a skilled fisherman, and can manage a curagh with extraordinary nerve and dexterity He can farm simply, burn kelp, cut out pampooties, mend nets, build and thatch a house, and make a cradle or a coffin. His work changes with the seasons in a way that keeps him free from the dullness that comes to people who have always the same occupation. The danger of his life on the sea gives him the alertness of the primitive hunter, and the long nights he spends fishing in his curagh bring him some of the emotions that are thought peculiar to men who have lived with the arts.

[やぶちゃん注:「

「繩綯ひは天氣の變り易い時、一方は小路で一方は茶の間で、行はれる」「一方は」は「或は」とするべきところ。天気が良ければ小路で、悪ければ茶の間で、の意。

「綯はれる」は「なはれる」と読む。「縄をなう」の「

「約五十ヤード位」凡そ45.7m。

「人はその中を拾ひ歩んで行かなければならない」縄だらけの道を縄を踏まないようにぬって歩かねばならない、ということ。

「犒ふ」は「ねぎらふ」と読む。「

「彼は熟練した漁夫で、……」確かに“he”が用いられているが、以下、段落の最後まで「彼」は「此の人達」「各人」を代表する、アランの「男」としての“he”である。邦訳では「彼等」と訳す方が分かりがよい。

「海上生活の危險は彼に原始時代の狩人の機敏さを教へ、カラハに乘つて釣をして過す長い夜は、藝術を友として生活する人に獨特と思はれる或る感情を彼に植ゑ付ける。」原文“The danger of his life on the sea gives him the alertness of the primitive hunter, and the long nights he spends fishing in his curagh bring him some of the emotions that are thought peculiar to men who have lived with the arts.”。この訳の後半はやや生硬である。『また、カラハに乗って釣りをして過ごす夜長には、芸術に生きる風流人士特有と思われている、ある種独特な繊細なる情緒を彼等にもたらす。』といった意味である。]

マイケルは晝間は忙しいので、私は毎日來て、愛蘭土語を讀んでくれる一人の男の子を得た。

その子は十五歳位で、非常に賢く、私たちの讀む言葉や物語に本當の好意を持つてくれる。

或る晩、私に二時間、本を讀んでくれた時、疲れたかと尋ねた。

「疲れたつて?」彼は答へた、「本を讀んで疲れることなんかありやしない。」

數年前まで、こんな知的傾向の少年達は年寄りの人達と一所に坐つて、その物語を覺えたものであらうが、今はこんな少年達は、ダブリンから來る愛蘭土語の本や新聞に心を向ける。

私たちの讀む大抵の物語には、英語と愛蘭土語の兩方が竝べてあるが、少し曖昧な章句になると、彼は英語の方を臨き見してゐるのを見かける。併しお前は愛蘭土語より英語の方がよくわかると私が云ふと、彼は憤慨した。彼は多分、英語よりも地方的な愛蘭土語の方がよくわかり、又印刷されると、愛蘭土語よりも英語の方がよくわかるのであらう。何故なら、印刷された愛蘭土語には彼のわからない地方的な形がよく出て來るからである。

二三日前、彼がダグラス・ハイド[Douglas Hide. 愛蘭土文藝復興の指導者の一人、同國の詩や傳説を集めて、その國語を以て書くことを努めた人]の「爐邊にて」[Beside the Fire]の中の傳説を讀んでゐると、譯の中で、彼の目に觸れた所があつた。

「英譯に一つ間違ひがある。」と云ひ、一寸躊躇した後で、「golden chair としないで gold chair としてある」と云つた。

私は、gold watches (金側時計)、gold pins (金の針)と云ふのだと教へた。

「何故さういふのかなあ。」彼は云つた。「golden chairの方がずつと綺麗なのに。」

初歩の學習が言葉の形式と共に思想までも、研究しようとする批評的精神の

或る日、私は紐繫ぎの奇術に言ひ及んだ。

「貴方が紐を繫ぐ筈がない。そんなことは云はないで下さい。」彼は云つた。「どんな風にして私たちを瞞したんだか知らないが、あの紐を繫いだのでは毛頭ないんだ。」

また或る日、一緒に居たが、煖爐の燃えが惡かつた。私は風道を作るため、その前に新聞紙を當てがつたが、餘り效果がなかつた。少年は何んとも云はなかつたが、私を馬鹿だと思つてゐたのであらう。

翌日、非常に

「爐に新聞紙を當てがつてやつてみた。」彼は云つた。「そしたら盛んに燃えた。貴方がやつてゐるのを見た時、全く駄目だとは思はなかつたが、先生(學校の先生)の家で爐で紙を當てがつたら、よく燃え上つた。それから紙の端をゆるめて頭を突込んでみたら、冷い風が煙突へ吹き上つてゐた。全く頭を吸ひ込まれさうになる程に。」

私たちは殆んど喧嘩をする所であつた。何故なら、土地の手織の方が島の原始的な生活を聯想さすので、遙かに彼に似合ふのであつたが、彼はそれを嫌つて、ゴルウェー産の晴着で、寫眞を撮つてくれと云ふからであつた。彼の鋭い氣性をもつて、苟くも世の中に踏み出すならば、やり通すことが出來るだらう。

彼は始終考へてばかりゐる。

或る日、島の人たちの名前は、國では大へん可笑しくはないかと聞いた。

私は少しも可笑しくはないと答へた。

「さうかね。」彼は云つた。「島では貴方の名前は大そう可笑しい。私たちの名前も國では、多分大そう可笑しいだらうと思つた。」

これは或る意味で道理がある。名前は此處で全く普通であるが、その名前は近代の姓氏法とは全く違つた方法を用ひてゐる。

子供が島の中を歩き出すと、村の人は彼をその

それでも充分に、いひ表はされない時は、その父の通り名――綽名かその父の名――が附け加へられる。

父の名が借りられない場合があるが、その時は、母の

此の宿の近くの或る婆さんは「ペギーン」と云はれるが、その息子は「パッチ・ペギーン」、「シォーン・ペギーン」等である。

時時、姓が愛蘭土式に用ひられるが、彼等同志で愛蘭土語を話してゐる時、「マック」(Mac)を上につけて用ひてゐるのを聞いた事がない。恐らく姓の考へは彼等にとつて餘り新し過ぎ、私の氣がつかない時に、時時使ふぐらゐなものであらう。

或る時は、その髮の毛の色から名附けられる。それでシォーン・ルア(赤毛のジョン)があり、その子供は「ムールティーン・シォーン・ルア」等である。

また或る人は「アン・イスガル」(漁夫)、その子供は「モーリャ・アン・イスガル」(漁夫の娘、メァリ)等として知られてゐる。

學校の先生が私に云つたが、朝、名簿を讀み上げる時、公けの名前の後では、子供たちが皆一緒に小聲で土地風の名前を繰り返す。するとその子供が返事をする。例へば先生が「パトリック・オフラハティ」と呼ぶと、子供たちは「パッチ・シォーン・ダルグ」と云ふやうな名前を小聲で云ふ。すると子供が返事をする。

此の島へ來る人も多く同じやうに取扱はれる。近頃フランス人のゲール語研究家が島に來たが、常に「アン・サガート・ルア」(赤毛の坊さん)、或は「アン・サガート・フランカハ(フランス人の坊さん)と呼ばれ、決して名前では呼ばれない。

若し島の人が、名前だけで通る場合には、それだけが用ひられる。私は「エーモン[エドモンドの愛蘭土名]と呼ばれる男を知つてゐる。島で他にも「エドモンド」といふ男があるかも知れないが、その場合には大概通常な綽名とか通り名とを持つてゐるのであらう。

他の國、例へば現代のギリシアのやうに、名前が幾分似寄つてゐる所では、その職業がその人を表はす最も普通の方法であるが、皆同じ職業を持つてゐる此處では、此の方法は役に立たない。

*

As Michael is busy in the daytime, I have got a boy to come up and read Irish to me every afternoon. He is about fifteen, and is singularly intelligent, with a real sympathy for the language and the stories we read.

One evening when he had been reading to me for two hours, I asked him if he was tired.

'Tired?' he said, 'sure you wouldn't ever be tired reading!'

A few years ago this predisposition for intellectual things would have made him sit with old people and learn their stories, but now boys like him turn to books and to papers in Irish that are sent them from Dublin.

In most of the stories we read, where the English and Irish are printed side by side, I see him looking across to the English in passages that are a little obscure, though he is indignant if I say that he knows English better than Irish. Probably he knows the local Irish better than English, and printed English better than printed Irish, as the latter has frequent dialectic forms he does not know.

A few days ago when he was reading a folk-tale from Douglas Hyde's Beside the Fire, something caught his eye in the translation.

'There's a mistake in the English,' he said, after a moment's hesitation, 'he's put "gold chair" instead of "golden chair."

I pointed out that we speak of gold watches and gold pins.

'And why wouldn't we?' he said; 'but "golden chair" would be much nicer.'

It is curious to see how his rudimentary culture has given him the beginning of a critical spirit that occupies itself with the form of language as well as with ideas.

One day I alluded to my trick of joining string.

'You can't join a string, don't be saying it,' he said; 'I don't know what way you're after fooling us, but you didn't join that string, not a bit of you.'

Another day when he was with me the fire burned low and I held up a newspaper before it to make a draught. It did not answer very well, and though the boy said nothing I saw he thought me a fool.

The next day he ran up in great excitement.

'I'm after trying the paper over the fire,' he said, 'and it burned grand. Didn't I think, when I seen you doing it there was no good in it at all, but I put a paper over the master's (the school-master's) fire and it flamed up. Then I pulled back the corner of the paper and I ran my head in, and believe me, there was a big cold wind blowing up the chimney that would sweep the head from you.'

We nearly quarrelled because he wanted me to take his photograph in his Sunday clothes from Galway, instead of his native homespuns that become him far better, though he does not like them as they seem to connect him with the primitive life of the island. With his keen temperament, he may go far if he can ever step out into the world.

He is constantly thinking.

One day he asked me if there was great wonder on their names out in the country.

I said there was no wonder on them at all.

'Well,' he said, 'there is great wonder on your name in the island, and I was thinking maybe there would be great wonder on our names out in the country.'

In a sense he is right. Though the names here are ordinary enough, they are used in a way that differs altogether from the modern system of surnames.

When a child begins to wander about the island, the neighbours speak of it by its Christian name, followed by the Christian name of its father. If this is not enough to identify it, the father's epithet--whether it is a nickname or the name of his own father--is added.

Sometimes when the father's name does not lend itself, the mother's Christian name is adopted as epithet for the children.

An old woman near this cottage is called 'Peggeen,' and her sons are 'Patch Pheggeen,' 'Seaghan Pheggeen,' etc.

Occasionally the surname is employed in its Irish form, but I have not heard them using the 'Mac' prefix when speaking Irish among themselves; perhaps the idea of a surname which it gives is too modern for them, perhaps they do use it at times that I have not noticed.

Sometimes a man is named from the colour of his hair. There is thus a Seaghan Ruadh (Red John), and his children are 'Mourteen Seaghan Ruadh,' etc.

Another man is known as 'an iasgaire' ('the fisher'), and his children are 'Maire an iasgaire' ('Mary daughter of the fisher'), and so on.

The schoolmaster tells me that when he reads out the roll in the morning the children repeat the local name all together in a whisper after each official name, and then the child answers. If he calls, for instance, 'Patrick O'Flaharty,' the children murmur, 'Patch Seaghan Dearg' or some such name, and the boy answers.

People who come to the island are treated in much the same way. A French Gaelic student was in the islands recently, and he is always spoken of as 'An Saggart Ruadh' ('the red priest') or as 'An Saggart Francach' ('the French priest'), but never by his name.

If an islander's name alone is enough to distinguish him it is used by itself, and I know one man who is spoken of as Eamonn. There may be other Edmunds on the island, but if so they have probably good nicknames or epithets of their own.

In other countries where the names are in a somewhat similar condition, as in modern Greece, the man's calling is usually one of the most common means of distinguishing him, but in this place, where all have the same calling, this means is not available.

[やぶちゃん注:「私たちの讀む言葉や物語に本當の好意を持つてくれる。」原文“with a real sympathy for the language and the stories we read.”。日本語でも注意深く読めば間違えないのであるが、この「私たちの讀む言葉や物語」「私たち」はシングとこの少年であり、「言葉や物語」とは、ゲール語やゲール語で書かれたケルト系の伝承を指している。

「ダグラス・ハイド[Douglas Hide. 愛蘭土文藝復興の指導者の一人、同國の詩や傳説を集めて、その國語を以て書くことを努めた人]古代ゲール語学者、ゲール語連盟・アイルランド民俗学協会(“the

Folklore of Ireland Society”)の設立者にして後の初代アイルランド共和国大統領Douglas Hyde(Dubhighlas

de Hide 1860年~1949年)。第二部の「コンノートの戀歌」“Love Songs of Connaught”(「コナハトの恋愛歌集」)の注参照。

『「爐邊にて」[Beside the Fire]』同上部分に既出。ダグラス・ハイドによるアイルランド民話や伝承の民俗学的集成。1910年刊。

「golden chair としないで gold chair としてある」は、『「金で出来た椅子」とせず、「金色をした椅子」とある。これ、如何?』という不服である。

「私は、gold watches (金側時計)、gold pins (金の針)と云ふのだと教へた」は、『

「初歩の學習が言葉の形式と共に思想までも、研究しようとする批評的精神の

「紙の端をゆるめて頭を突込んでみたら」は、「よく燃え上がった炉の火口全体に宛がっていた新聞の端に少し隙間を作って、試みに自分の頭部を近づけて見たら」という意味であろう。

「私たちは殆んど喧嘩をする所であつた。……」原文は“We nearly quarrelled because he wanted me to take his photograph in his Sunday clothes from Galway, instead of his native homespuns that become him far better, though he does not like them as they seem to connect him with the primitive life of the island.”と長いので姉崎氏は主文の主述を頭に持ってきたのであろうが、これも日本語としてはかなり不親切な印象を与える。その内容は前を受けるのではなく、後の写真の件を受けるということが読み終わらないと分からないからである。意訳しても、ここは前に「また、ある時のこと、……」と頭に附けるだけで、それは解消されるはずだ。栩木氏はこの主述部分を日本語として、巧みに後に持ってきて、原文通りの一文で訳しておられる。分かり易い非常によい訳であると思う。

「近代の姓氏法」原文は“the modern system of surnames”で、これは所謂、相手を当時のヨーロッパで汎用されていた人を呼称・呼名する場合の方法・使用名についての習慣やマナーの謂いである。

「父の名が借りられない場合があるが、その時は、母の

「ペギーン」“Peggeen”という名は、後のシングの名作にして問題作“The Playboy of the Western World”「西部の人気者」(1907年)のヒロインの名である。彼女は本名は“Margaret Flaherty”(マーガレット・フラハルティ)だが、通称“Pegeen Mike”(ペギーン・マイク)である(舞台となる酒場の主人である彼の父は“Michael James Flaherty”(マイケル・ジェイムズ・フラハルティ)である)。因みに、ゲール語の“Peggeen”は“pearl”(真珠)の意である。

「(Mac)」言わずもがなであるが、“Mac-”は“son of”(~の息子)の意の接頭語で、アイルランド及びスコットランド系の姓の頭に見られるのだが、その姓名命名法の古形であるアランでは逆に用いられることがないのではないか、とシングは言っているのである(断定は出来ないから、段落末では留保はしている)。

『「アン・イスガル」(漁夫)』原文“an iasgaire' ('the fisher')”。栩木氏は『アン・チャスカラ』と音写されている。

『「モーリャ・アン・イスガル」(漁夫の娘、メァリ)』原文“'Maire an iasgaire' ('Mary daughter of the fisher')”。栩木氏は『モーラ・アニャスカラ』と音写されている。

「パッチ・シォーン・ダルグ」原文“Patch Seaghan Dearg”。栩木氏は『パッツィ・ショーン・デャルグ』と音写されている。

「サガート」原文“Saggart”。ゲール語で「司祭の家」という意味らしい。栩木氏は「神父」と訳されており、「サガーチ」と音写されている。]

今日、夕方遲くなつて、漕手の外に二人のお婆さんを乘せた三挺擢のカラハが、大きいうねりの中を上陸しょうとするのを見た。此の人達はインニシールから來たのである。忽ちのうちに寄波の線内數ヤードの所へ漕いで來て、其處で轉囘し、舳先を海の方へ向けて止つた。その間に、波は次々その下を通り拔けて、船卸臺の殘部に碎けた。五分經ち、十分經つたが、彼等は未だに擢を水にひたしながら待ち、首を肩越に後へ向けてゐた。

彼等は斷念して、島の風下の方へ漕ぎ廻らなければならないだらうと、私は思ひかけた。するとその時、カラハは突然生き物のやうに變つた。水煙の中を驅りながら、跳びながら、舳先は再び船卸臺の方へ向けられた。到着しないうちに船首にゐた男がくるつと向を變へたと思ふ間に、劍の閃きのやうに二つの白い脚が舳先を越えて出で、次の波の來ないうちに、カラハを危險から曳き出した。

此の男たちの咄嗟の協同した動作は、訓練があるのではないが、波が彼等に與へた教育である事がよくわかる。カラハが無事にはひると、二人のお婆さんはその息子の脊をかりて、寄波や滑り易い海草の中を連れて來られた。

こんな變り易い天氣に、カラハが出れば必ず危險な目に逢ふが、事故は稀で、殆んどきまつて飮酒に起因するらしい。昨年、私が此處へ來てから、四人の男が大島から歸る途中、溺死した。

最初のは南島のカラハで、酒にしたたか醉つた二人の男を乘せて出かけた。翌日の晩、帆を半分かけ、濡れもせず、壞れもせずに此の島へ打ち上げられたが、中には誰も居なかつた。

もつと最近では、此の島から出かけたカラハで、飮酒で危險になつてゐる三人の男を乘せてゐたが、歸る途中で轉覆した。汽船が近くにゐたので、二人は助けられたが、三人目までには及ばなかつた。

さてドニゴールの岸に、一人の男が打ち上げられた。その男は一つの革草鞋をつけ、縞のシャツを着、そのポケットの一つには財布と煙草入があつた。 三日の間、此處の人達は此の男の身元を確かめようとしてゐた。或る人は此の島の男だと考へ、また或る人は南島から來た異に人相書がよく合つてゐると考へた。今晩、舟卸臺から歸る途中、此の島から行つて溺れた男の母親に逢つたが、まだ海の方を眺めて泣いてゐた。彼女は南島から來た人を止めては、あちらではどんな風に考へられてゐるかと、こわごわ小聲で尋ねてゐた。

夕方遲く、私が或る家に居た時、死んだ男の妹が子供を連れて雨の中をやつて來て、屆いた噂話を長い間してゐた。彼女はその着物の事、財布の體裁やそれを買つた處について、覺えてゐるだけを考へ合はせてゐた。また煙草入や靴下についても同じやうにしてゐた。終にそれが兄の物である事に、少しの疑ひもないやうであつた。

「あゝ!」と彼女は云つた。「マイクの物に違ひない。神樣、どうぞあの人を淸らかに葬り下さいますやうに。」

それから、彼女は祕かに泣唱を初めた。黄色い髮の毛は雨に濡れて首にくつついてゐた。子供に乳を飮ませながら扉の傍に坐つてゐる所は、島の女の生活の典型であるかのやうに見えた。

暫くの間、人人は何も云はずに坐つてゐた。子供の乳を吸ふ音、庭に降り注ぐ雨の音、一隅に寢てゐる豚の鼾のほかには、何の音も聞こえなかつた。それから一人の男が、新しいボートが南島に送られた事などを話し出したが、話はいつも同じ話題に戻るのであつた。

一人の男の死は、直接の肉親の者以外のすべての者にとつては一つの些細な破滅であるらしい。よく不慮な災難が起つて、父親と上の息子の二人が一緒に死ぬといふやうなことがある。またどうかして、家族の働き手全部が死ぬといふやうなこともある。

二三年前、今でも島で使つてゐる木の器――小さな桶のやうな――を作るのが、商賣であつた家の三人の男が一緒に大島に行つた。歸り途で皆溺死したので、小さな桶を造る

去年の冬起つたもう一つの破滅は、祝祭日の慣例に一つの奇妙な興趣を添へた。祝祭日の晩に、男たちが漁に出るのは習慣ではないらしい。ところが、去年の十二月の或る夜、幾人かの男たちが、翌朝早く釣を初めようと思つて、漕ぎ出して、漁船の中で寢た。

すると朝近くなり、恐ろしい嵐が吹き起り、幾艘かの漁船は、その船員たちを乘せたまま碇泊地から吹き流されて難船した。波が高かつたので、救助の手段を試みることも出來ず、男たちは溺死したのであつた。

「ああ!」此の話をしてくれた男は言つた。「これから祝祭日に、男たちが二度と海へ出かけることは當分なくなるだらう。その嵐は、その冬を通じて、港にまでとどいた、たつた一度きりのものだつた。これには何か譯があつたのだらう。」

*

Late this evening I saw a three-oared curagh with two old women in her besides the rowers, landing at the slip through a heavy roll. They were coming from Inishere, and they rowed up quickly enough till they were within a few yards of the surf-line, where they spun round and waited with the prow towards the sea, while wave after wave passed underneath them and broke on the remains of the slip. Five minutes passed; ten minutes; and still they waited with the oars just paddling in the water, and their heads turned over their shoulders.

I was beginning to think that they would have to give up and row round to the lee side of the island, when the curagh seemed suddenly to turn into a living thing. The prow was again towards the slip, leaping and hurling itself through the spray. Before it touched, the man in the bow wheeled round, two white legs came out over the prow like the flash of a sword, and before the next wave arrived he had dragged the curagh out of danger.

This sudden and united action in men without discipline shows well the education that the waves have given them. When the curagh was in safety the two old women were carried up through the surf and slippery seaweed on the backs of their sons.

In this broken weather a curagh cannot go out without danger, yet accidents are rare and seem to be nearly always caused by drink, Since I was here last year four men have been drowned on their way home from the large island. First a curagh belonging to the south island which put off with two men in her heavy with drink, came to shore here the next evening dry and uninjured, with the sail half set, and no one in her.

More recently a curagh from this island with three men, who were the worse for drink, was upset on its way home. The steamer was not far off, and saved two of the men, but could not reach the third.

Now a man has been washed ashore in Donegal with one pampooty on him, and a striped shirt with a purse in one of the pockets, and a box for tobacco.

For three days the people have been trying to fix his identity. Some think it is the man from this island, others think that the man from the south answers the description more exactly. To-night as we were returning from the slip we met the mother of the man who was drowned from this island, still weeping and looking out over the sea. She stopped the people who had come over from the south island to ask them with a terrified whisper what is thought over there.

Later in the evening, when I was sitting in one of the cottages, the sister of the dead man came in through the rain with her infant, and there was a long talk about the rumours that had come in. She pieced together all she could remember about his clothes, and what his purse was like, and where he had got it, and the same for his tobacco box, and his stockings. In the end there seemed little doubt that it was her brother.

'Ah!' she said, 'It's Mike sure enough, and please God they'll give him a decent burial.'

Then she began to keen slowly to herself. She had loose yellow hair plastered round her head with the rain, and as she sat by the door sucking her infant, she seemed like a type of the women's life upon the islands.

For a while the people sat silent, and one could hear nothing but the lips of the infant, the rain hissing in the yard, and the breathing of four pigs that lay sleeping in one corner. Then one of the men began to talk about the new boats that have been sent to the south island, and the conversation went back to its usual round of topics.

The loss of one man seems a slight catastrophe to all except the immediate relatives. Often when an accident happens a father is lost with his two eldest sons, or in some other way all the active men of a household die together.

A few years ago three men of a family that used to make the wooden vessels--like tiny barrels--that are still used among the people, went to the big island together. They were drowned on their way home, and the art of making these little barrels died with them, at least on Inishmaan, though it still lingers in the north and south islands.

Another catastrophe that took place last winter gave a curious zest to the observance of holy days. It seems that it is not the custom for the men to go out fishing on the evening of a holy day, but one night last December some men, who wished to begin fishing early the next morning, rowed out to sleep in their hookers.

Towards morning a terrible storm rose, and several hookers with their crews on board were blown from their moorings and wrecked. The sea was so high that no attempt at rescue could be made, and the men were drowned.

'Ah!' said the man who told me the story, 'I'm thinking it will be a long time before men will go out again on a holy day. That storm was the only storm that reached into the harbour the whole winter, and I'm thinking there was something in it.'

[やぶちゃん注:「ドニゴールの海岸」“ashore in Donegal”はイニシマーンにある海岸の固有地名であるが、同名でアイルランド北西部の州があり、このドニゴール (ゲール語“Dún na nGall”)とは、「外国人の砦」(アイルランド人にとっての「外国人」でヴァイキングを指す)に由来するという。

「此の島から行つて溺れた男の母親」原文は“the mother of the man who was drowned from this island”。確かに海で消えた(可能性が高い)のだから、“drown”(溺れる・溺死する)と用いているのであろうが、後の「死んだ男の妹」“the

sister of the dead man”も合わせて、シングの書き方自体が上手くない。これではネタバレしているのと同じである。ここは私は意訳(“drown”には「音が消える」の意があり、これは消息が絶えることだ。また“dead

man”は必ずしも「死んだ男」と訳さねばならないわけではない。「消滅した男」の意味もある)をしても、「此の島からアランモアへ行って帰る折りに行方知れずとなってしまったイニシマーンの男の母親」、「さっきの消息不明のイニシマーンの男の妹」としたいのである。本話は後のシングの戯曲“Rider

to the Sea”(海に行く騎手)に生かされる。その作中で溺死する若者の名もマイク(マイケル)である。

「暫くの間、人人は何も云はずに坐つてゐた。子供の乳を吸ふ音、庭に降り注ぐ雨の音、一隅に寢てゐる豚の鼾のほかには、何の音も聞こえなかつた。それから一人の男が、新しいボートが南島に送られた事などを話し出したが、話はいつも同じ話題に戻るのであつた。」原文“For a while the people sat silent, and one could hear nothing but the lips of the infant, the rain hissing in the yard, and the breathing of four pigs that lay sleeping in one corner. Then one of the men began to talk about the new boats that have been sent to the south island, and the conversation went back to its usual round of topics.”。ここは「アラン島」の中でも映像的に(SEからも)頗る印象的なシークエンスである。細かいことを言うと、原文では「四匹の豚」である。また、最後の姉崎氏の訳は誤読される虞がある。叙情的な読みをする人は「いつも同じ話題」とは、「死んだ男」の話題という風に読みがちであろうが、ここは次の段落の冒頭に示される通り、「一人の男の死は、直接の肉親の者以外のすべての者にとつては一つの些細な破滅で」しかないのであり、小さな声から普通の声へと移り変わる彼らの話の内容は、もう「死んだ男」の話題ではなく、普段の日常的な話柄へと変じていたことを指しているのである。そうした画面全体(向こうでは、相変わらず男の妹が赤ん坊に乳をやりながら死んだ兄を悼む泣唱を奏でている)を撮る監督シングは、正しくタルコフスキイの先駆者である。

「去年の冬起つたもう一つの破滅は、祝祭日の慣例に一つの奇妙な興趣を添へた。」原文“Another catastrophe that took place last winter gave a curious zest to the observance of holy days.”。最後が生硬。「奇妙な興趣を添へた」は「妙に熱烈な信心の習慣を添えた」、則ち、祝日には仕事をしてはならない、すればろくなことはない、命をも落とすのだ、という頑ななまでのジンクスが広く信じられるようになった、ということである。直後に述べているように、日本のお盆の殺生禁断と同様に、アラン島でも祝祭日には漁に出ることは、恐らく日本的な禁忌というよりも、習慣として祝祭日は安息するもの、と考えられていたのであろうが、この事故をきっかけに「何か譯があつた」→「祝祭日」→多くの島民がそうした禁忌を熱心に信じ始める、という経過を描いているのである。]

今日、私は船卸臺へ行つた時、キルロナンから來た豚の仲買が、英國の市場へ船に積んで持つて行く廿匹ほどの豚を連れてゐるのを見た。

汽船が近づいて來ると、その豚の群全部が船卸臺に移され、カラハは海近く運んで來られた。

それから豚は順順に捕へられ、横樣に投げ出された。その間に豚の脚は、運ぶ時のために繩の尾を殘して、一重結びに縛られた。

受ける痛みは大したものでもなささうであつたが、其奴等は目をつぶつて全く人間のやうな聲で叫び、遂にその聲は何かを訴へるやうに、段段激しくなつて行つたので、ただ眺めてゐた男女達も興奮して騷ぎ出した。豚は順を待ちながら口から泡を吹き、互ひに嚙み合ひをしてゐた。

少し經つてから、中休みが來た。船卸臺全部は啜り泣く豚の群で一杯になつた。その群の中に、怖がつてゐる女が所所に交り、しやがんで特に好きな豚を靜かにさせようと、撫でてゐた。その間に、カラハは下ろされた。

それからまた泣き聲が初まつた。それは、豚が運び出され、帆布を傷めないやうに、脚の周りに胴着を附けられてそれぞれの場所に置かされる間ぢゆうであつた。それ等は何處へ行くのか知つてゐかのやうに見えた。船緣に動物ながらぐつたりとして、私の方を眺めてゐるのを見ると、私は此の啜り泣いてゐる動物の肉を食つてゐたのかと思ひ、ぞつとした。最後のカラハが出て行つてしまふと、船卸臺の上は私と女子供の一團と、海の方を眺めて坐つてゐる年取つた牡豚とだけになつた。

女たちは非常に興奮してゐた。私が話しかけようとすると、私の周りにどつと集まつて來て、私の結婚してないのを理由にひやかし初め、喚き初めた。一度に大勢が叫び立てて、而かも早口なので何を云つてゐるのかわからないが、夫の留守を幸に、その惡口を一齊に云ひ立ててゐるのだと見當をつけた。これを聞いてゐた或る男の子たちは笑ひこけて、海草の中へ轉んだ。また若い娘たちは氣まり惡さうに、顏を赤くして、波をじつと見下ろしてゐた。

暫くの間、私は狼狼してしまつた。物を云はうと思つても、こちらの云ふことを聞かすことが出來なかつた。それで船卸臺の上に腰掛けて、寫眞の袋を取り出した。すると忽ち、通常の氣持で、犇き合つて來る一團の人に私はすつかり取り圍まれた。

カラハが戻つて來ると、――その中の一艘は波の上に大へんな恰好で、蜻蛉返りを打つて浮かんでゐた大きな茶の間用テーブルを引張つてゐた、――キャニゥィエ(行商人)が來たと云ふ聲が起つた。

上陸すると、彼は直ぐに店を開いて、娘たちや若い女たちに安物のナイフや寶石をたくさん賣りつけた。彼は愛蘭土語を話さなかつたが、値の掛引が、取卷いてゐる大勢の人たちを非常に面白がらせた。

幾人かの女たちは英語を知らないと云つてゐるくせに、氣に向いた時には、苦もなく云ひたい事を通じさせてゐるのを見て、私は驚いた。

「此の指環はあんまり高いです。」或る女はゲール語の構造法を使ひながら云つた。「もつと少い金にしなさい、さうしたら女の子は皆んな買ふでせう。」

寶石の次には安物の宗教畫――いやな

*

Today when I went down to the slip I found a pig-jobber from Kilronan with about twenty pigs that were to be shipped for the English market.

When the steamer was getting near, the whole drove was moved down on the slip and the curaghs were carried out close to the sea. Then each beast was caught in its turn and thrown on its side, while its legs were hitched together in a single knot, with a tag of rope remaining, by which it could be carried.

Probably the pain inflicted was not great, yet the animals shut their eyes and shrieked with almost human intonations, till the suggestion of the noise became so intense that the men and women who were merely looking on grew wild with excitement, and the pigs waiting their turn foamed at the mouth and tore each other with their teeth.

After a while there was a pause. The whole slip was covered with a mass of sobbing animals, with here and there a terrified woman crouching among the bodies, and patting some special favourite to keep it quiet while the curaghs were being launched.

Then the screaming began again while the pigs were carried out and laid in their places, with a waistcoat tied round their feet to keep them from damaging the canvas. They seemed to know where they were going, and looked up at me over the gunnel with an ignoble desperation that made me shudder to think that I had eaten of this whimpering flesh. When the last curagh went out I was left on the slip with a band of women and children, and one old boar who sat looking out over the sea.

The women were over-excited, and when I tried to talk to them they crowded round me and began jeering and shrieking at me because I am not married. A dozen screamed at a time, and so rapidly that I could not understand all that they were saying, yet I was able to make out that they were taking advantage of the absence of their husbands to give me the full volume of their contempt. Some little boys who were listening threw themselves down, writhing with laughter among the seaweed, and the young girls grew red with embarrassment and stared down into the surf.

For a moment I was in confusion. I tried to speak to them, but I could not make myself heard, so I sat down on the slip and drew out my wallet of photographs. In an instant I had the whole band clambering round me, in their ordinary mood.

When the curaghs came back--one of them towing a large kitchen table that stood itself up on the waves and then turned somersaults in an extraordinary manner--word went round that the ceannuighe (pedlar) was arriving.

He opened his wares on the slip as soon as he landed, and sold a quantity of cheap knives and jewellery to the girls and the younger women. He spoke no Irish, and the bargaining gave immense amusement to the crowd that collected round him.

I was surprised to notice that several women who professed to know no English could make themselves understood without difficulty when it pleased them.

'The rings is too dear at you, sir,' said one girl using the Gaelic construction; 'let you put less money on them and all the girls will be buying.'

After the jewellery' he displayed some cheap religious pictures--abominable oleographs--but I did not see many buyers.

I am told that most of the pedlars who come here are Germans or Poles, but I did not have occasion to speak with this man by himself.

[やぶちゃん注:「カラハは海近く運んで來られた。」“the curaghs were carried out close to the sea.”とは、舟卸臺より上に引き上げられていたカラハが、豚を汽船に移送するために、海面近くまで降ろされることを言っている。

「怖がつてゐる女」“a terrified woman”。女たちは、豚のパニックに感染して、テンションが異様に昂まっている。その中でも特に気持ちが動転して、凝っとしていられないヒステリー気質の女性を指している。

「年取つた牡豚」“one old boar”。“boar”は去勢していない雄豚の意。種豚である(食肉用の去勢した雄豚は“hog”という)。

「夫の留守を幸に、その惡口を一齊に云ひ立ててゐるのだと見當をつけた。」原文は“yet I was able to make out that they were taking advantage of the absence of their husbands to give me the full volume of their contempt.”であるが、まず姉崎氏の訳では「その悪口」の「その」が彼らの夫を指していることになり、これは私は誤りであると思う。“their contempt”とは、私は彼らがシング個人へ向けた「聞くに堪えないえげつない物言い」(その内実は分からぬにせよ)を指しているものと思うのである。例えば栩木氏もこれを『僕に最大限の侮辱をぶつけているらしい』と訳しておられることから、姉崎氏の誤訳と考えるのである。ただ私は「惡口」も「侮辱」もピンとこないである。これは直前で「私の結婚してないのを理由にひやかし初め、喚き初めた」ことから分かるように、定められたパートナーを持たない若者シングへの、ある種の性的な揶揄なのである。「夫の留守を幸」、更に豚パニックでエクサイトしてテンション揚がりっぱなしの女たちがするそれは、とても夫のいる前では恥ずかしくて口に出来ないようなセクシャルな毒や誘惑を含んだ話柄なのであり、だからこそ「これを聞いてゐた或る男の子たちは笑ひこけて、海草の中へ轉」げまわるのであり、「また若い娘たちは氣まり惡さうに、顏を赤くして」、『……あの人たちの言っていること、私には分からないわ、そんなの、興味ないわ……』、という困惑と含羞から、あらぬ彼方の「波をじつと見下ろしてゐ」るのである。だから私は、ここは「夫の留守を幸」、私に対して、秘めごとに関わるようなえげつない物言い「を一齊に云ひ立ててゐるのだと見當をつけた。」と意訳したいのである。ここは民俗的な描写としてすこぶる面白いシークエンスである。シングがもう少しゲール語を解していて、その語句や言い回しをここに残していてくれたら、もっと素晴らしかったのだが……。

「その中の一艘は波の上に大へんな恰好で、蜻蛉返りを打つて浮かんでゐた大きな茶の間用テーブルを引張つてゐた、」“one of them towing a large kitchen table that stood itself up on the waves and then turned somersaults in an extraordinary manner”。このテーブルは、恐らく汽船から離れた時には、カラハの後の何らかの筏のようなものの上に正常な形で置かれていたのであろうが、波に揉まれてその筏か牽引用のアタッチメントのようなものが損壊し、テーブルがもんどりうって――逆さま(足を上にして)になり――しかし深く沈潜することなく、奇体に脚を海から突き出して運ばれた一部始終を一文で述べたものと私は解釈する。

「キャニゥィエ(行商人)」“ceannuighe (pedlar)”の“ceannuighe”はゲール語と思われる。“pedlar”は“peddler”とも綴り、行商人・麻薬密売人の外、噂などを好んで言い触らす輩の意など、余りよいイメージの言葉ではない。如何にも怪しげな行商人に相応しい単語だ。

「ゲール語の構造法」ゲール語の構文法では、英語のようなSVOではなく、動詞を最初に持ってくるVSO型を取る。

「いやな

私は二三日前から、南島へ來てゐる。例の如く、渡航は惠まれなかつた。

その朝笑氣がよく、冬の初めの雨の降る前によくある獨特な妙に靜かな澄んだ日となる兆があつた。夜が明けかかつた時から、空は一面の白雲に蔽はれ、あらゆる物音も一つ一つ靜かな灣の上を渡つて響いて來ると思へるまで、全くの靜けさであつた。靑い煙は輪を描いて村の上に立上つてゐた。遙か沖合、水平線の上には、雨雲がちぎれちぎれに重く懸つてゐた。私たちはその日、朝早く出發したが、海は遠くからは靜かに見えたが、岸を離れて行くと、西南から來る相當なうねりに逢つた。

瀨戸の眞中近くで、船首で漕いでゐた男がその櫂栓を壞したので、普通のカラハの操作はむつかしくなつた。なにしろ三人漕のカラハなので、若し海がこれ以上荒れたら、甚だ危險な目に出逢ふことになるであらう。進行がのろかつたので、私たちが岸に着かないうちに、風に乘つて雲がどんどんやつて來て、大粒の雨が降り出した。灰色の世界の中を黑いカラハは靜かに進んで行くと雨は靜かに降りそそぐので、私は我我が世界の凡ゆる不思議や美しさを經驗しようと殘して置いた短い瞬間を無限の悲哀を以つて實感するやうな氣持になつた。

南島の船着場は、西北方の立派な砂濱にできてゐる。此の岩の途切れは村人にとつて大いに役に立つ。併し、濡れた砂の道はその上に近頃建てられたいやな漁夫の家が何軒かあつて、はつきりしない天氣の時は、特に淋しく見える。

上陸した時は、汐が退いてゐたので、カラハをただ濱に上げただけで、小さなホテルへ上つて行つた。一つの部屋で税の集金人が仕事をしてゐた。四邊に大勢の男たちや子供たちが待つてゐて、私たちが戸口に立つて旅館の主人と話をしてゐる間、こちらを見つめてゐた。

私たちは一杯飮んでしまふと、非常に行手を急いでゐる男たちと一緒に私は海の方へ下りて行つた。櫂栓を取換へるのに少し時を費し、風はまだ吹き募つてゐたが、彼等は出かけた。多くの漁夫達が出立を見にやつて來た。私は彼等の言葉や氣分を他の島で經險したそれと較べてみたくて仕方がなかつたので、カラハの姿が見えなくなつた後も長い間立つて、愛蘭土語で話をした。

中には今まで聞いた事もないほど明瞭に、愛蘭土語を話す者さへゐたが、言葉は同一のやうであつた。併し體の形、服裝、一般的の性質には可成りの差異があつたやうである。此の島の住民は隣島の住民より進歩してゐて、社會は段段と各階級を造りつつある、即ち富裕な者、一生懸命に働かねばならぬ者、全くの貧乏で貯蓄のない者である。此の區別は中の島にも現はれてゐるが、住民に影響する程ではなく、彼等の中にはまだ完全な平等がある。

少したつて、汽船の姿が見え出し、沖に碇泊した。カラハが出かけてしまつてゐる間、人々の中に襤褸を着て滑稽味のある型の幾人かの男達がゐた。かつては斯かる人達が愛蘭土の本當の百姓を代表してゐたのであらう。雨は激しく降つてゐた。霧を通して外を眺めてゐると、これ等の人達の中で、甚だ不恰好な頓智のある一人の男が擧げてゐる甲高い笑ひ聲には、何んだかぞつとするやうなところがあつた。

遂に彼は上衣の端で目を拭き「タ・メ・モラヴ」(私は殺される)と、獨り呻りながら村の方へ去つたが、遂に誰かに呼び止められた。すると粗野な酒落や冗談をまたとばして笑ひ出したが、それには何か言葉以上の意味がありさうであつた。

中の島には、奇妙な諧謔、時には野生の諧謔もあるが、こんな半ば肉慾的な陶醉の笑ひ方はない。恐らく此の人達は世を嘲らうとする前に、あちらでは知られてない内奧の不幸を感ずるに違ひない。その窪んだ額、高い頰骨、反抗的な目を持つた此の不思議な人達は歐洲の邊境の僅かな土地に住む古風な型を代表してゐるやうに見える。そして其處で、彼等は野生の冗談や笑ひに依つてのみ僅かにその淋しさとやるせなさを表現し得るのである。

*

I have come over for a few days to the south island, and, as usual, my voyage was not favourable.

The morning was fine, and seemed to promise one of the peculiarly hushed, pellucid days that occur sometimes before rain in early winter. From the first gleam of dawn the sky was covered with white cloud, and the tranquillity was so complete that every sound seemed to float away by itself across the silence of the bay. Lines of blue smoke were going up in spirals over the village, and further off heavy fragments of rain-cloud were lying on the horizon. We started early in the day, and, although the sea looked calm from a distance, we met a considerable roll coming from the south-west when we got out from the shore.

Near the middle of the sound the man who was rowing in the bow broke his oar-pin, and the proper management of the canoe became a matter of some difficulty. We had only a three-oared curagh, and if the sea had gone much higher we should have run a good deal of danger. Our progress was so slow that clouds came up with a rise in the wind before we reached the shore, and rain began to fall in large single drops. The black curagh working slowly through this world of grey, and the soft hissing of the rain gave me one of the moods in which we realise with immense distress the short moment we have left us to experience all the wonder and beauty of the world.

The approach to the south island is made at a fine sandy beach on the north-west. This interval in the rocks is of great service to the people, but the tract of wet sand with a few hideous fishermen's houses, lately built on it, looks singularly desolate in broken weather.

The tide was going out when we landed, so we merely stranded the curagh and went up to the little hotel. The cess-collector was at work in one of the rooms, and there were a number of men and boys waiting about, who stared at us while we stood at the door and talked to the proprietor.

When we had had our drink I went down to the sea with my men, who were in a hurry to be off. Some time was spent in replacing the oar-pin, and then they set out, though the wind was still increasing. A good many fishermen came down to see the start, and long after the curagh was out of sight I stood and talked with them in Irish, as I was anxious to compare their language and temperament with what I knew of the other island.

The language seems to be identical, though some of these men speak rather more distinctly than any Irish speakers I have yet heard. In physical type, dress, and general character, however, there seems to be a considerable difference. The people on this island are more advanced than their neighbours, and the families here are gradually forming into different ranks, made up of the well-to-do, the struggling, and the quite poor and thriftless. These distinctions are present in the middle island also, but over there they have had no effect on the people, among whom there is still absolute equality.

A little later the steamer came in sight and lay to in the offing. While the curaghs were being put out I noticed in the crowd several men of the ragged, humorous type that was once thought to represent the real peasant of Ireland. Rain was now falling heavily, and as we looked out through the fog there was something nearly appalling in the shrieks of laughter kept up by one of these individuals, a man of extraordinary ugliness and wit.

At last he moved off toward the houses, wiping his eyes with the tail of his coat and moaning to himself 'Tá mé marbh,' ('I'm killed'), till some one stopped him and he began again pouring out a medley of rude puns and jokes that meant more than they said.

There is quaint humour, and sometimes wild humour, on the middle island, but never this half-sensual ecstasy of laughter. Perhaps a man must have a sense of intimate misery, not known there, before he can set himself to jeer and mock at the world. These strange men with receding foreheads, high cheekbones, and ungovernable eyes seem to represent some old type found on these few acres at the extreme border of Europe, where it is only in wild jests and laughter that they can express their loneliness and desolation.

[やぶちゃん注:「灰色の世界の中を黑いカラハは靜かに進んで行くと雨は靜かに降りそそぐので、私は我我が世界の凡ゆる不思議や美しさを經驗しようと殘して置いた短い瞬間を無限の悲哀を以つて實感するやうな氣持になつた。」原文は“The black curagh working slowly through this world of grey, and the soft hissing of the rain gave me one of the moods in which we realise with immense distress the short moment we have left us to experience all the wonder and beauty of the world.”。後半が極めて生硬で意味が取れない。“moods”は複数形であるから、「不機嫌」、ネガティヴな傾向への気持ちの沈潜を意味する。「灰色の世界の中を黑いカラハは靜かに進んで行く」……そして……私に「雨は靜かに降りそそぐ」……そんな眼前の重く陰鬱な景色が……私をある一つの暗く沈んだ思念へと導いてゆく――それは、私たちが私たちのために「世界の凡ゆる不思議や美しさを經驗しようと殘して置いた」時間、その時間が如何に短いものであるかということを――私はこの瞬間に「無限の悲哀を以つて實感」したのであった、という意味であろう。

「近頃建てられたいやな漁夫の家」とは、如何にも近代的な、アランの自然の景観にそぐわない「いやな」感じのする漁師の家、という意味であろう。

「遂に誰かに呼び止められた」“till some one stopped him”。「遂に」は日本語としておかしい。「ふと誰かに呼び止められた。」でよい。

「それには何か言葉以上の意味がありさうであつた」とあるが、彼がつぶやく「タ・メ・モラヴ」(私は殺される)]にしても――これは今まで読んでこられた方は第一部のパット爺さんの妖精に攫われた娘の話を思い出されるであろう。『また或る夜、愛蘭土語で「オー・ウォホイル・ソ・メー・モラヴ」(ああ、お母さん、殺される)といふ叫び聲を彼は聞いたが、朝になつてその家の塀に血がついてゐて、そこから程遠からぬ處に、その家の子供は死んでゐた。』という例の話である――私はこの男のこの言葉は、偶然の一致では、ないと思う。それは「死」を言上げすることで、逆に死を遠ざける効果を持つ。「ぞつとする」「甲高い笑ひ聲」は死を忌避するための非日常的ポーズなのである。だからここで呼び止められた彼が飛ばした「粗野な酒落や冗談」と、その後の不気味な「半ば肉慾的な陶醉の笑ひ」は、恐らく民俗的な言霊を内包した呪言なのである。シングの中の原初的無意識がそれに直感的に気づいたから、彼は「ぞつと」し、また「それには何か言葉以上の意味がありさう」だと感じたのである。但し、それをシングが完全なプロトタイプとしては判断していないところが微妙で複雑なのである。次の段落にそれが示されている。則ち、確かにこの男の「何か言葉以上の意味」を持った「粗野な酒落や冗談」やそれに付随する不気味な「半ば肉慾的な陶醉の笑ひ」はアランの昔の百姓の古形に属する――だが、イニシマーン島の、近代思想に殆んど犯されていない純朴なプロトタイプと比較した時、イニシーアのこの男は、明らかに近代文明のカルチャー・ショックをその感性がネガティヴに受けて、イニシマーンの島民に「は知られてない内奧の不幸を感ずる」ようになってしまっているのである。「その窪んだ額、高い頰骨、反抗的な目を持つた此の不思議な人達は」「古風な型を代表してゐるやうに見える」けれども、純粋に古形ではない、文明にレイプされて「野生の冗談や笑ひに依つてのみ僅かにその淋しさとやるせなさを表現」するしかない、ある種の哀れみさえ感じさせるまでに零落している、とシングは語るのである。換言すれば「歐洲の邊境の僅かな土地」という卑屈な認識をイニシーアの島民は持ってしまっている(恐らくアランモアはもっとえげつなく近代化されてしまっている)のに対して、シングの愛するイニシマーンの人々は誰もが美しい魂の古形をしっかりと保存している、と言っているのである。]

此の島の民謠を歌ふ風は極めて荒つぽいものである。今日、東の方の村はづれで、妙な男と一緒になつて、海の方の岩の上までぶらぶら歩いて行つた。一緒に居る間に、冬の時雨が來て、私たちは疎らな石垣の下の蕨の中に

節は前に此の邊の島島で聞いたものとよく似てゐた――音律をつけるために高い音と低い音の後に休止を置く、抑揚のない歌であつた。併し鼻にかかつた耳觸りな聲で歌ふのは殆んどやりきれなかつた。歌ひ振りは、その全體として私がかつてパリーからディエプまで旅行した時、三等車の中で東洋人の一行から聞いた歌を憶ひ出させた。併し此の島人は聲をもつと廣い範圍に操つた。

彼の發音は喉に掠れて聞こえなくなる。はつきり自分の云ふことをわからせようと、風の音に負けずに私の耳もとで叫んだが、それは或る若者が海へ行つて多くの冐險をする運命を物語つた長たらしい民話とだけ見當をつけられたに過ぎなかつた。英語の航海用語が、その船中生活を描くために始終使つてあるが、それが出て來ると、此の男は辻褄が合はなくなると思ふのであらう、暫く止めて、私を指で突いたりして、船首の三角帆、中檣帆、第一斜檣などを説明した。ところが、私にそれ等は一番よくわかる個所であつた。再び場面がダブリンに移ると、「ウィスキーの盃」・「酒屋」といふやうなものに就いて英語で話した。

時雨が終ると、海から僅かに離れて童の中に隠れた妙な洞穴を見せてくれた。歸り途で、私の何處へいつても出逢ふ三つの質問をした。――私が金持であるか、結婚してゐるか、此の島より貧しい所を他所で見た事があるか。

私が結婚してゐないと聞くと、彼は、私が夏歸つて來たら、「スプリー・モール・オグス・ゴ・ラル・レイディース」(大きな酒宴と澤山の婦人)のあるクレア郡の

此の人と一緒にゐるのが私には何んだかいやであつた。私は親切に心を廣くしてゐるのであつたが、彼は私が嫌つてゐると思つたらしい。夜また逢ふ約束をしたので云ふに云はれないいやな束縛で重い足を引きずりながらその場所へ行つたが、彼は影も形も見せなかつた。

此の男は大方呑兵衞で、密造酒販賣人であるらしく、又確かに貧乏人に違ひなかつたが、私が嫌つてゐると感じたので、一シリングを貰ふ機會を拒んだのは此の男特有の氣質である。彼は妙に強情と憂鬱の交つた顏をしてゐた。大方その素質のために、島の評判がよくなく――友達から同情を得る事のない人の不安な氣持で、此處に住んでゐるのであらう。

*

The mode of reciting ballads in this island is singularly harsh. I fell in with a curious man to-day beyond the east village, and we wandered out on the rocks towards the sea. A wintry shower came on while we were together, and we crouched down in the bracken, under a loose wall. When we had gone through the usual topics he asked me if I was fond of songs, and began singing to show what he could do.

The music was much like what I have heard before on the islands--a monotonous chant with pauses on the high and low notes to mark the rhythm; but the harsh nasal tone in which he sang was almost intolerable. His performance reminded me in general effect of a chant I once heard from a party of Orientals I was travelling with in a third-class carriage from Paris to Dieppe, but the islander ran his voice over a much wider range.

His pronunciation was lost in the rasping of his throat, and, though he shrieked into my ear to make sure that I understood him above the howling of the wind, I could only make out that it was an endless ballad telling the fortune of a young man who went to sea, and had many adventures. The English nautical terms were employed continually in describing his life on the ship, but the man seemed to feel that they were not in their place, and stopped short when one of them occurred to give me a poke with his finger and explain gib, topsail, and bowsprit, which were for me the most intelligible features of the poem. Again, when the scene changed to Dublin, 'glass of whiskey,' 'public-house,' and such things were in English.

When the shower was over he showed me a curious cave hidden among the cliffs, a short distance from the sea. On our way back he asked me the three questions I am met with on every side--whether I am a rich man, whether I am married, and whether I have ever seen a poorer place than these islands.

When he heard that I was not married he urged me to come back in the summer so that he might take me over in a curagh to the Spa in County Glare, where there is 'spree mor agus go leor ladies' ('a big spree and plenty of ladies').

Something about the man repelled me while I was with him, and though I was cordial and liberal he seemed to feel that I abhorred him. We arranged to meet again in the evening, but when I dragged myself with an inexplicable loathing to the place of meeting, there was no trace of him.

It is characteristic that this man, who is probably a drunkard and shebeener and certainly in penury, refused the chance of a shilling because he felt that I did not like him. He had a curiously mixed expression of hardness and melancholy. Probably his character has given him a bad reputation on the island, and he lives here with the restlessness of a man who has no sympathy with his companions.

[やぶちゃん注:「民謠」原文は“ballads”。民謡・バラード。民間伝承の物語詩に節をつけた歌謡。短いスタンザ(連)から成り、リフレインが多い。

「ディエプ」“Dieppe”(ディエップ)はフランスのオート=ノルマンディー地域圏にあるセーヌ=マリティーム県のコミューン(フランス固有の地方自治体)。イギリス海峡に面した港町。

「辻褄が合はなくなると思ふ」言うまでもないが、ゲール語で語るアイルランド固有のバラードであるはずであるから、そこに英語が入り込むのはおかしいのである。

「船首の三角帆」原文“gib”。機械用語で、凹字形をした

「中檣帆」は「ちゅうしょうほ」又は「ちゅうしょはん」と読む。原文“topsail”。トップスル。帆船でマストの中段に張られた帆を言う。

「第一斜檣」「斜檣」は「しゃしょう」と読む。原文“bowsprit”。船首斜檣、やり出し、バウスプリット。帆船の船首に突き出しているマスト状の丸太材を言う。

『「スプリー・モール・オグス・ゴ・ラル・レイディース」(大きな酒宴と澤山の婦人)のある』原文は“where there is 'spree mor agus go leor ladies' ('a big spree and plenty of ladies').”。姉崎氏の訳はゲール語でこのような名を持つスパ(高級鉱泉保養施設)のように訳されているが(そのような誤読をするように訳されているが)、これは「とんでもないどんちゃん騒ぎ(オーギー)と数多の接待の御婦人方が待っている」といった意味である。

「クレア郡」原文は“County Glare”となっているが、これはCの誤植であろう。クレア州(“County Clare” ゲール語“Contae an Chláir”)。アラン諸島の東、ゴルウェー灣の南側にある。]

私は再び、イニシマーンに戻つて來た。今度の渡航は良い天候であつた。朝早くから、太陽は空一杯に輝き渡り、正午にカラハで迎へに來たマイケルと、他の二人の男と共に出發した時は、殆んど夏の日であつた。

風は都合よく吹いたので、帆を擧げ、マイケルは舟尾にゐて櫂で舵を取り、一方私は他の男と共に漕いだ。

私たちはよく食ひ、よく飮んだ。そして此の突然の夏の再來に段段と刺戟されて來て、夢のやうな充ち足りたよい氣持になり、青く輝く海を越えて我が聲も響けとばかり、嬉しさに思はず大聲を立てた。

丁度南島の人達にならつてゐるやうに、此のイニシマーンの男たちも外界に對して妙に昔ながらの同感に心を動かすやうである。彼等の氣持は今日の天氣具合に驚くほどよく合ひ、またその古いゲール語は貴い單純さに充ちてゐるので、私は船を西へ廻はし、彼等と共に永久に漕いでゐたかつた。

私は、數日中にパリーに歸つて本や寢臺を賣り、それからまた、此の西の島島にゐる人たちのやうに強健で單純になるために戻つて來るつもりだと彼等に話した。

私たちの感激が鎭まつた頃、マイケルは將に坊さんの置いて行つた鐵砲があり、島へ戻つて來るまで使ふことを許されてゐると云つた。家にはもうーつの鐵砲と白鼬が一匹あるから、歸つたら直ぐに兎狩に連れて行かうと彼は云つた。

その日、少し遲くなつて出かけた。マイケルは私が立派な射撃をやつてほしいと熱心なのには私は殆んど笑ひたくなるほど可笑しかつた。

私たちは白鼬を二つの平らな裸岩の間の裂目に匿して、待つてゐた。間もなく、足下に驅けて來る足音を聞いたと思ふと、一匹の兎が、足下の穴から一目散に宙へ飛び上り、二三尺向うの石垣の方へ逃げて行つた。私は鐵砲を摑み上げて、撃つた。

マイケルは岩を騷け上りながら、私の肘の所で、「ブーイル・テゥ・エ」(中つたよ)と大聲で叫んだ。私は仕留めたのである。

それから一時間の間に、私たちは七八匹を撃つたので、マイケルは非常に喜んだ。若し私がまづかつたら、島から逃げ出さねばならなかつたであらう。島の人たちは私を輕蔑したであらう。

撃つことの出來ない「ドゥイネ・ウァソル」(旦那)は此の獵人の子孫である人たちから背教者よりもだめな墮落した人間と思はれるのである。

*

I have come over again to Inishmaan, and this time I had fine weather for my passage. The air was full of luminous sunshine from the early morning, and it was almost a summer's day when I set sail at noon with Michael and two other men who had come over for me in a curagh.

The wind was in our favour, so the sail was put up and Michael sat in the stem to steer with an oar while I rowed with the others.

We had had a good dinner and drink and were wrought up by this sudden revival of summer to a dreamy voluptuous gaiety, that made us shout with exultation to hear our voices passing out across the blue twinkling of the sea.

Even after the people of the south island, these men of Inishmaan seemed to be moved by strange archaic sympathies with the world. Their mood accorded itself with wonderful fineness to the suggestions of the day, and their ancient Gaelic seemed so full of divine simplicity that I would have liked to turn the prow to the west and row with them for ever.

I told them I was going back to Paris in a few days to sell my books and my bed, and that then I was coming back to grow as strong and simple as they were among the islands of the west.

When our excitement sobered down, Michael told me that one of the priests had left his gun at our cottage and given me leave to use it till he returned to the island. There was another gun and a ferret in the house also, and he said that as soon as we got home he was going to take me out fowling on rabbits.

A little later in the day we set off, and I nearly laughed to see Michael's eagerness that I should turn out a good shot.

We put the ferret down in a crevice between two bare sheets of rock, and waited. In a few minutes we heard rushing paws underneath us, then a rabbit shot up straight into the air from the crevice at our feet and set off for a wall that was a few feet away. I threw up the gun and fired.

'Buail tu é,' screamed Michael at my elbow as he ran up the rock. I had killed it.

We shot seven or eight more in the next hour, and Michael was immensely pleased. If I had done badly I think I should have had to leave the islands. The people would have despised me. A 'duine uasal' who cannot shoot seems to these descendants of hunters a fallen type who is worse than an apostate.

[やぶちゃん注:原文では、以下、文章が続いているが、内容的には切るべきである。

「丁度南島の人達にならつてゐるやうに、此のイニシマーンの男たちも外界に對して妙に昔ながらの同感に心を動かすやうである。」原文は“Even after the people of the south island, these men of Inishmaan seemed to be moved by strange archaic sympathies with the world.”。これは誤訳の類と言っていいような気がする。日本語は「~のやうに、……も――」という完全な順接の複文になっているが、そもそも日本語として読んでいて文脈上、矛盾が感じられるからだ。前段でイニシーアの島民の悪い意味での近代化による陰鬱傾向を一貫して批判してきたシングが、その「南島の人達に」「イニシマーンの男たち」が「ならつてゐる」などと言うはずが、ない。この“Even”は「全く」の意味ではあるまいか。「ああしたどこか陰気な南島の人々と接した後では、全くも以って、このイニシマーンの男たちが実に素直に外界に対する不思議な、昔ながらの共感によって心を働かしているようにしみじみと感じられるのである。」という意味であろう。私は、強調された、逆接的な日本語として訳さないとおかしいと感じる。このシークエンスは久々にまばゆい陽光とシングの大好きなイニシマーンの人々との魂の美しい交感の場面であるだけに、この瑕疵は痛い。

「白鼬」は「しろいたち」と読む。原文は“ferret”で、今や「フェレット」で通用する。食肉(ネコ)目イタチ科イタチ亜科イタチ属ヨーロッパケナガイタチ亜種

Mustela putorius furo。ヨーロッパではフェレットは古くから家畜とされており、フェレットにウサギなどの獲物を巣穴から追い出させて狩るという狩猟法で、現在でも残っている。]

此の島の女達は未だ因習に捉はれてゐず、パリーやニューヨークの女に獨持と思はれる自由な特色を幾らか持つてゐる。

彼女たちの多くは裝飾的興味以上の物を持つには餘りに滿足しきつて居り、あまりにがつちりして居るが、また面白い個性を持つた女もある。

今年は私は大へんおもしろい一人の娘を知るやうになつた。彼女は二三日前から茶の間で、お婆さんの

それに似たものを私はドイツの女やポーランドの女の聲に聞いたことがあるが、女よりも遙かに單純な動物的感情から離れてゐる男――少くとも歐州の男――とか、或ひは佛語・英語のやうな弱い喉音の言葉を使ふ人とかには、日常の會話で、こんな不明瞭な調を出すことは出來ないであらう。

彼女は女がよくやるやうに示小詞を重ねたり、文章法を滑稽に無視して、形容詞を繰り返へしたりして、彼女のゲール語で

今夜は私が爐邊の椅子に腰掛ける最後の晩である。私は、別れの挨拶をしにやつて來た村人達と長い間話しをした。彼等は頭を低い腰掛に載せ、足を泥炭の燃え差しの方へ伸ばし、床の上に横になつた。お婆さんは爐と反對の側に居て、さつきの娘は誰彼となく話したり冗談を云つたりして、紡車の前に立つてゐた。彼女は、私が歸つたら持參金の澤山ある金持の女と結婚し、その女が死んだらまた此處へ來て、彼女を第二の妻として迎へてくれと云つた。

此の人達の話ほど、純樸でまた愛嬌のあるのを聞いた事がない。今夜は妻といふものに就いて議論が出たが、彼等が女に於いて見る最大の長所は多産的で澤山の子供を産むことにあるやうであつた。島では子供に依つて金儲は出來ないが、此の一つの心の持ち方は此處の人達とパリーの人達との大いなる相違を現はしてゐる。

島では、あから樣な性の本能も弱い事はないが、それは家族愛の本能に從屬してゐるので、無手法になる事は滅多にない。此處の生活はまだ殆んど家長制度の段階にあるので、野蠻人の本能的な生活から遙かに離れてゐると同樣に、空想的な戀の情緒にも緣が遠い。

*

The women of this island are before conventionality, and share some of the liberal features that are thought peculiar to the women of Paris and New York.

Many of them are too contented and too sturdy to have more than a decorative interest, but there are others full of curious individuality.

This year I have got to know a wonderfully humorous girl, who has been spinning in the kitchen for the last few days with the old woman's spinning-wheel. The morning she began I heard her exquisite intonation almost before I awoke, brooding and cooing over every syllable she uttered.

I have heard something similar in the voices of German and Polish women, but I do not think men--at least European men--who are always further than women from the simple, animal emotions, or any speakers who use languages with weak gutturals, like French or English, can produce this inarticulate chant in their ordinary talk.

She plays continual tricks with her Gaelic in the way girls are fond of, piling up diminutives and repeating adjectives with a humorous scorn of syntax. While she is here the talk never stops in the kitchen. To-day she has been asking me many questions about Germany, for it seems one of her sisters married a German husband in America some years ago, who kept her in great comfort, with a fine 'capull glas' ('grey horse') to ride on, and this girl has decided to escape in the same way from the drudgery of the island.

This was my last evening on my stool in the chimney corner, and I had a long talk with some neighbours who came in to bid me prosperity, and lay about on the floor with their heads on low stools and their feet stretched out to the embers of the turf. The old woman was at the other side of the fire, and the girl I have spoken of was standing at her spinning-wheel, talking and joking with every one. She says when I go away now I am to marry a rich wife with plenty of money, and if she dies on me I am to come back here and marry herself for my second wife.

I have never heard talk so simple and so attractive as the talk of these people. This evening they began disputing about their wives, and it appeared that the greatest merit they see in a woman is that she should be fruitful and bring them many children. As no money can be earned by children on the island this one attitude shows the immense difference between these people and the people of Paris.

The direct sexual instincts are not weak on the island, but they are so subordinated to the instincts of the family that they rarely lead to irregularity. The life here is still at an almost patriarchal stage, and the people are nearly as far from the romantic moods of love as they are from the impulsive life of the savage.

[やぶちゃん注:原文では、以下、文章が続いているが、やはり内容的には切るべきである。

「此の島の女達は未だ因習に捉はれてゐず、パリーやニューヨークの女に獨持と思はれる自由な特色を幾らか持つてゐる。」 “The women of this island are before conventionality, and share some of the liberal features that are thought peculiar to the women of Paris and New York.”の前の部分は、この島の女たちの感性が、誠に稀有なことに、歴史的な「制度としての因襲」によって縛られる以前の段階に踏みとどまっていることを言っている。そして「にも拘らず」(と逆接風に)、知的で先進的な「パリーやニューヨークの女に獨持と思」われがちな、リベラルな特徴部分をも持ち合わせているのだ、という意味である。

「彼女たちの多くは裝飾的興味以上の物を持つには餘りに滿足しきつて居り、あまりにがつちりして居るが、また面白い個性を持つた女もある。」失礼ながら、この前半は日本語としては悪文である。原文は“Many of them are too contented and too sturdy to have more than a decorative interest, but there are others full of curious individuality.”であるが、これは「彼女たちの多くが、ここでここの女として生きることに満足しきっていて、加えてとてつもなくがっしりとして丈夫であるから――失礼ながら私には、アラン島というこの魅力的な世界を、見た眼で美しく装い飾る存在という以上の関心は、彼女たちに持つことは出来ないのであるが――しかし」また中にはすこぶる魅力的な「面白い個性を持つた女もある」という謂いであろう。栩木氏もそうしたコンセプトで訳されておられる。この部分は続く後半も、シングにしてはかなり踏み込んだ島の女についての叙述がなされている。紳士にして少年性を持ったシングは、アランの女たちを傷つけないように遠回しに(というより飽くまで民俗学的な謂いに包んで)表現しているという気が私にはする。

「不明瞭な調」「調」は「しらべ」と読ませていよう。原文は“this inarticulate chant”で、これは「この不明瞭な詠唱」の謂いである。これはこの女のゲール語の会話が、喋っているのか歌っているのかちょっと分からないような独特の音楽的なある種の調べを持っていることを意味している。

「示小詞」“diminutive”は文法用語の「指小辞」のこと。ある語について、それよりもさらに小さい意を示したり、親愛の情を表したりする接尾語のこと。例えば英語の“-ie”“-kin”“-let”“-ling”、ドイツ語の“-lein”“-chen”など。

「……大事にしてくれるので、此の娘もそんな風にして……」この日本語はやはり違和感がある。「大事にしてくれるのだと言った。その口ぶりからはどうも此の娘もそんな風にして……」としたい。

「島では子供に依つて金儲は出來ないが」これは、子供を有意な労働力と認識して、専ら子供に労働をさせて金を稼がせることは出来ないという意味である。アランにはそんな賃金を払ってくれる仕事も何もないという意味もあろうが、それ以上にアランの人々(厳密にはイニシマーンの人々)には、伝統的な家父長制による縛りはあるものの(しかし前出する第一部に出た「谷間の影」「西部の人気者」のモデルとなった話を見ると、それも決して強靭なものとは思われない)、子供を単純に労働力と見、彼らの収益を親が簒奪することを当然とするような親子関係はやや希薄であることをも言っているように思われる。マイケルもそうだが、若者の多くは島を出て働いているが、彼らが親の主たる生計維持者であるようには、私には必ずしも読めないのである。

「無手法に」は「むてつぱふに(むてっぽうに)」と読む。]

今朝は汽船が着くかどうか少し怪しかつたほど、風が強かつた。それで、半日をマイケルと一緒に、水平線を眺めながらぶらぶら歩いて過した。

遂に斷念した時、汽船が遙か北の方に姿を見せた。汽船は波の最も高い處で追風を受けねばならぬので、そちらの方を通るのであつた。

私は宿から荷物を取り出し、マイケルや爺さんと一緒に船卸臺の方へ出かけ、此處彼處へさよならを云ひに立寄つた。

外の風にもかかはらず船卸臺の所の海は池のやうに靜かであつた。船が南島に寄つてゐる間、そこらに立つてゐる人達は、私がまた彼等に逢ひに來る時には結婚してゐるかどうかを、これを最後と問題にしてゐた。それから私たちは漕ぎ出して行つて、列の中に位置を占めた。汐が激しく流れてゐたので、汽船は岸から相當離れて止つた。その舷側のよい位置を占めるためには長い競爭をするやうになつた。一生懸命にやつたが、私たちの方は餘り成功しなかつた。それで甲板へ上るために、うねりで曲り、ぐらぐら搖れるカラハを二つ越えて、攀ぢ上らねばならなかつた。

見知り顏の人を大勢乘せてゐるカラハが私を連れずに、船卸臺の方へ引返して行くのを見るのは妙な感じがしたが、瀨戸のうねりは直ぐに、私の注意をその方へそらした。船には南島で逢つた幾人かの人が乘つてゐた。また澤山のゴルウェーから歸りがけの人もゐた。此の人達は朝渡つて來る途中海の一所で大暴れに逢つたと語つてゐた。

土曜日の例として、船はキルロナンに下ろす小麥や黑ビールの澤山の荷を積んでゐた。そして汐が波止場に船を浮ばせないうちに、四時近くなつたので、ゴルウェ一に渡るのは少し怪しく思はれた。

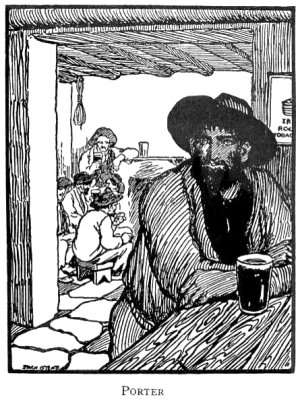

午後が下るにつれて、風は吹き募つて來た。夕方の薄明りの中を下りて行くと、荷物はまだすつかりは下ろされてゐず、船長は盛んになる強風を衝いて行くのを心配してゐるのであつた。彼が最後の決定を下すまでには時間がかかつた。私たちは、厚い雲が頭の上を飛び、風が石垣に吠えてゐる村を行つたり來たりした。終に彼は翌日用があるかどうかを知らうとゴルウェ一に電報を打つた。その返事を待つため、私たちは酒場にはひつた。

茶の間には、爐の兩側に長い列を作つてぎつしりと、人が一杯に坐つてゐた。粗野な顏をしてゐるが美しい一人の娘の子が爐邊に膝をついて男達と大聲に話してゐた。また幾人かのイニシマーンの土地の人は身汚く醉つて扉に凭れてゐた。茶の間の奧には酒飮場が設けてあり、その傍の奧の間のやうな處では、老人達が幾人かトランプをしてゐた。頭の上のむき出しの垂木には、炭や煙草の煙が一杯であつた。

これは他の島の女達に非常に恐れられてゐる場所である。此處で、男達は金を懷にして長尻し、遂によろめく足取りで外へ出て、瀨戸で命を墜してしまふのである。男たちが毎晩毎晩安いウィスキーや黑ビールを飮み、漁のこと、海草灰のこと、煉獄の苦しみのことを繰り返し繰り返し語りながら坐つてゐる此の簡單な遊び場に、

ウィスキーを飮み終ると、船は留まるかも知れないといふ聲が起つた。

やつとの事で荷物を汽船から出した。そしてそれを、小麥粉の袋、石油の罐の名状すべからざるほどごたごたした中で、揉み合ひ押し合ひしてゐる女達や驢馬の群を押し分けて運び上げた。

宿に着くと、お婆さんの機嫌は大へんよかつた。暫く茶の間の爐で話しながら時間を費した。それから暗い道を手探りして港へ引返した。其處では、最初私が島へ來た時に逢つた網繕ひの爺さんが夜番をしてゐると聞いたからであつた。

波止場は眞暗で、恐ろしい嵐が吹いてゐた。彼がゐるだらうと思つた小さな事務所には誰もゐないので、ランターンの燈で動いてゐる人影の方へ、手探りしてまた進んで行つた。

それは爺さんであつた。挨拶して私の名を云ふと直ぐに憶ひ出した。暫くの間、ランターンの用意をしてゐて、それから私をその事務所――波止場で進行中の仕事の請負師のため、建てた板と生子鐵板の只の小屋--に連れて行つてくれた。

私たちが燈の所に來た時、私は、寒さ除けに途方もなく何枚も襟卷をしてゐる彼の頭を見た。その顏には今でも、多分に賢さうな所があるが、此の前逢つた時よりは餘程年取つて見えた。

彼は四五十年前、船給仕となつて、初めて島を離れた時、ダブリンで私の親戚に逢ひに行つた顚末を語り出した。

彼は例の如く詳しく話した。――

*

[

The wind was so high this morning that there was some doubt whether the steamer would arrive, and I spent half the day wandering about with Michael watching the horizon.

At last, when we had given her up, she came in sight far away to the north, where she had gone to have the wind with her where the sea was at its highest.

I got my baggage from the cottage and set off for the slip with Michael and the old man, turning into a cottage here and there to say good-bye.

In spite of the wind outside, the sea at the slip was as calm as a pool. The men who were standing about while the steamer was at the south island wondered for the last time whether I would be married when I came back to see them. Then we pulled out and took our place in the line. As the tide was running hard the steamer stopped a certain distance from the shore, and gave us a long race for good places at her side. In the struggle we did not come off well, so I had to clamber across two curaghs, twisting and fumbling with the roll, in order to get on board.

It seemed strange to see the curaghs full of well-known faces turning back to the slip without me, but the roll in the sound soon took off my attention. Some men were on board whom I had seen on the south island, and a good many Kilronan people on their way home from Galway, who told me that in one part of their passage in the morning they had come in for heavy seas.

As is usual on Saturday, the steamer had a large cargo of flour and porter to discharge at Kilronan, and, as it was nearly four o'clock before the tide could float her at the pier, I felt some doubt about our passage to Galway.

The wind increased as the afternoon went on, and when I came down in the twilight I found that the cargo was not yet all unladen, and that the captain feared to face the gale that was rising. It was some time before he came to a final decision, and we walked backwards and forwards from the village with heavy clouds flying overhead and the wind howling in the walls. At last he telegraphed to Galway to know if he was wanted the next day, and we went into a public-house to wait for the reply.

The kitchen was filled with men sitting closely on long forms ranged in lines at each side of the fire. A wild-looking but beautiful girl was kneeling on the hearth talking loudly to the men, and a few natives of Inishmaan were hanging about the door, miserably drunk. At the end of the kitchen the bar was arranged, with a sort of alcove beside it, where some older men were playing cards. Overhead there were the open rafters, filled with turf and tobacco smoke.

This is the haunt so much dreaded by the women of the other islands, where the men linger with their money till they go out at last with reeling steps and are lost in the sound. Without this background of empty curaghs, and bodies floating naked with the tide, there would be something almost absurd about the dissipation of this simple place where men sit, evening after evening, drinking bad whisky and porter, and talking with endless repetition of fishing, and kelp, and of the sorrows of purgatory.

When we had finished our whiskey word came that the boat might remain.

With some difficulty I got my bags out of the steamer and carried them up through the crowd of women and donkeys that were still struggling on the quay in an inconceivable medley of flour-bags and cases of petroleum. When I reached the inn the old woman was in great good humour, and I spent some time talking by the kitchen fire. Then I groped my way back to the harbour, where, I was told, the old net-mender, who came to see me on my first visit to the islands, was spending the night as watchman.

It was quite dark on the pier, and a terrible gale was blowing. There was no one in the little office where I expected to find him, so I groped my way further on towards a figure I saw moving with a lantern.

It was the old man, and he remembered me at once when I hailed him and told him who I was. He spent some time arranging one of his lanterns, and then he took me back to his office--a mere shed of planks and corrugated iron, put up for the contractor of some work which is in progress on the pier.

When we reached the light I saw that his head was rolled up in an extraordinary collection of mufflers to keep him from the cold, and that his face was much older than when I saw him before, though still full of intelligence.

He began to tell how he had gone to see a relative of mine in Dublin when he first left the island as a cabin-boy, between forty and fifty years ago.