[島の男]

The Aran Islands

Part Ⅱ

by J. M. Synge

With drawings by Jack B. Yeats

Dublin, Maunsel & Co., Ltd.

[1907]

アラン島

第二部

ジョン・ミリングトン・シング著

ウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツ挿絵

ダブリン マウンセル社刊

姉崎正見訳

附 やぶちゃん注

[島の男]

The Aran Islands

Part Ⅱ

by J. M. Synge

With drawings by Jack B. Yeats

Dublin, Maunsel & Co., Ltd.

[1907]

アラン島

第二部

ジョン・ミリングトン・シング著

ウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツ挿絵

ダブリン マウンセル社刊

姉崎正見訳

附 やぶちゃん注

[やぶちゃん注:本頁は私のブログでの第二部の公開を経て、第二部全文を一括して作成したものである。底本・凡例及び解説は第一部を参照されたい。今回、明らかな脱字と思われる箇所には【 】で字を補った。――これを私と同じく母を失う聖痕(スティグマ)を受けた教え子に捧げる――【2011年3月19日

私の最愛の母聖子テレジアの一周忌に】]

第 二 部

西部に歸る前の晩、マイケル――本土へ稼ぎに行くため島を離れてゐる――に手紙を出し、日曜である次の朝、彼の宿を訪ねたいと云ふ事を云つてやつた。

私が案内を乞ふと、西部型の美しい顏の英語を知らない若い女が出て來た。私の事をすつかり聞いてゐるらしく、用向の大事なことを思ひ込んで、それを云ふが殆んどわからない。

「彼女は貴方のお手紙を受取りました。」と西部でよくやるやうに人稱代名詞を交ぜこぜにして云ふ。「彼女は今、彌撒に行つてゐます。その後で廣場に行きませう。濟みませんが、今、廣場に行つて、腰掛けてゐて下さい。さうすればマイケルはまゐりませう。」

本通りに引返して行くと、私を待ちくたびれたやうに、マイケルが私に逢ひに、ぶらぶらやつて來るのに出逢つた。

彼は、逢はないでゐるうちに、強さうな男になつて、コンノートの勞働者の着る濃い茶色のフランネルを着てゐた。少し話をした後、一緒に引返して來て、町の上にある砂山に出かけた。私の宿の入口から少し離れた此處で彼に逢ふと、その純な性質が、新しい生活からも又彼の交はる町の人たちや船乘りたちからも殆んど影響をうけてゐないのを特に感心した。

「私は日曜には、よく郊外へ出かけます。」彼は話の中で云つた。「仕事をしてない時に、町の人の大勢居る中にゐたつて仕方がありませんからね。」

暫くして、愛蘭土語も使へるもう一人の勞働者――マイケルの友だち――を加へて、草の上に横になつて、數時間しやべつたり、議論したりした。その日は堪らなく蒸暑く、近くの砂濱や海には半裸體の女が大勢いたが、此の二人の若者は彼等の存在に氣づかぬ風であつた。町に歸る前、横になつてゐる近くの砂の上に、-人の男が小馬を追ひ込みに現れた。それを此の友達たちは非常に面白がつた。

夕方遲く、再びマイケルに逢ひ、全く暗くなるまで灣に沿うて散歩したが、其處にはまだ海水浴をしてゐる女たちが大勢居た。明日は彼は忙しく、火曜には私は汽船で出立するので、もう島から戻るまで彼には逢へないであらう。

*

Part II

THE EVENING before I returned to the west I wrote to Michael--who had left the islands to earn his living on the mainland--to tell him that I would call at the house where he lodged the next morning, which was a Sunday.

A young girl with fine western features, and little English, came out when I knocked at the door. She seemed to have heard all about me, and was so filled with the importance of her message that she could hardly speak it intelligibly.

'She got your letter,' she said, confusing the pronouns, as is often done in the west, 'she is gone to Mass, and she'll be in the square after that. Let your honour go now and sit in the square and Michael will find you.'

As I was returning up the main street I met Michael wandering down to meet me, as he had got tired of waiting.

He seemed to have grown a powerful man since I had seen him, and was now dressed in the heavy brown flannels of the Connaught labourer. After a little talk we turned back together and went out on the sandhills above the town. Meeting him here a little beyond the threshold of my hotel I was singularly struck with the refinement of his nature, which has hardly been influenced by his new life, and the townsmen and sailors he has met with.

'I do often come outside the town on Sunday,' he said while we were talking, 'for what is there to do in a town in the middle of all the people when you are not at your work?'

A little later another Irish-speaking labourer--a friend of Michael's--joined us, and we lay for hours talking and arguing on the grass. The day was unbearably sultry, and the sand and the sea near us were crowded with half-naked women, but neither of the young men seemed to be aware of their presence. Before we went back to the town a man came out to ring a young horse on the sand close to where we were lying, and then the interest of my companions was intense.

Late in the evening I met Michael again, and we wandered round the bay, which was still filled with bathing women, until it was quite dark, I shall not see him again before my return from the islands, as he is busy to-morrow, and on Tuesday I go out with the steamer.

[やぶちゃん注:「西部に歸る前の晩」原文 “THE EVENING before I returned to the west”。何でもないことだが、姉崎氏が「歸る」と訳されたのが無性に嬉しい。

「用向の大事なことを思ひ込んで、それを云ふが殆んどわからない」原文は“and was so filled with the importance of her message that she could hardly speak it intelligibly.”で、要は殆んど英語が出来ないのに加えて、シングにマイケルからの大事な再会するための要件を伝えねばならないという緊張のあまり、その喋りが、当初、全く達意でない、まるで分からなかった、という意味。後の、「私を待ちくたびれたやうに、マイケルが私に逢ひに、ぶらぶらやつて來るのに出逢つた」という描写が、その意思疎通に想像を絶する時間が掛かったことを意味していよう。

「コンノート」“Connaught”。“Connacht”(ゲール語では“Connachta”であるが、現地では慣習上“Cúige Chonnacht”と書く)とも綴り、アイルランド島北西部の地方。「コナハト」「コンノート」とも音写するが、現地音に最も近いのは「コナハト」。アイルランド王コルマクの息子コン“Conn”の子孫の国の意。ゴールウェイ・リートリム・メイヨー・ロスコモン・スライゴの6州から成る。中心は南部がゴールウェイ市、北部がスライゴ市で、現在もゲール語が一部の地域(ゲールタハト:アイルランドの言語回復を図るためにアイルランド自由国政策の一部として公認されたゲール語公用語地域)で話されている(以上はウィキの「コノート」によった)。

「近くの砂濱や海には半裸體の女が大勢いた」“and the sand and the sea near us were crowded with

half-naked women”。この半裸体というのはどの程度の露出を言うのであろう。いや、真面目に気になるのである。因みに、私の古くからの御用達の「サイトX51」には、17世紀ヨーロッパに於いては「女性がおっぱいを晒すのはごく普通の事だった」という事実を明らかにした女性の歴史研究家の記事があるのである。]

今朝、私はキルロナン行の汽船で、中の島へ戻つて來た。そして鹽魚を積んで行くカラハで此處へ來た。船卸臺から上つて行くと、村の入口は女や子供で一杯であつた。中には道へ出て來て、私の手を握つて、熱心な歡迎の言葉を述べてくれる者もあつた。

パット・ディレイン爺さんは死に、數人の友達はアメリカへ行つてしまつた。それが私の數ケ月居なかつた後で知らされたニュースの全部であつた。

宿に着くと、老人たちから歡迎され、持つて來た少しの土産物――お婆さんには折疊式の鋏、爺さんには革砥、その他雜多な物――で大賑ひを呈した。

するとまだ家にゐる一番末の息子のコランプが奧の部屋へ行つて、昨年、私が出立の時送つた目覺時計を持つて來た。

「僕は此の時計が大好きだよ。」彼はその背中を撫でながら云つた。「漁に出たいと思ふ朝は、いつでも鳴つてくれる。いや、これに適ふ鷄は島中に二羽とゐないだらう。」

私は、昨年此處で撮つた數葉の寫眞を彼等に見せようと持つてゐた。茶の間の戸の傍で椅子に腰掛けて、それを家の人たちに見せてゐると、昨年屢々云つたことのある美しい若い女がそつとはひつて來て、非常に簡單に而かも懇ろに挨拶をしてから、同じやうに寫眞を見ようと私の傍の床下に坐り込んだ。

此の人たちの大部分がはにかみも自意識も全く持つてゐないのは、彼等に美しい魅力を與へる。此の若い美しい女が氣に入つた寫眞をもつと近くで見ようと、私の膝越しに凭れかかつた時、私は常にもまして島の生活の不思議な純樸さを感じた。

昨年、私が此處へ來た時、何もかも新しく、人人は少し私に

私の此の島で撮つた寫眞が大いに喜ばれて、その中の一人一人が――手や足だけ見えてゐる人までが――みんなわかつてしまふと、私はウィクロー郡で撮つた物をいくつか取り出した。それ等は大部分、ラスドラムやオーリムの市場、或は丘の上で芝を刈つてゐる男たち、その他内地の生活の光景の寫つてゐる斷片ではあつたが、海に飽きてゐる人たちには大へん喜ばれた。

*

I returned to the middle island this morning, in the steamer to Kilronan, and on here in a curagh that had gone over with salt fish. As I came up from the slip the doorways in the village filled with women and children, and several came down on the roadway to shake hands and bid me a thousand welcomes.

Old Pat Dirane is dead, and several of my friends have gone to America; that is all the news they have to give me after an absence of many months.

When I arrived at the cottage I was welcomed by the old people, and great excitement was made by some little presents I had bought them--a pair of folding scissors for the old woman, a strop for her husband, and some other trifles.

Then the youngest son, Columb, who is still at home, went into the inner room and brought out the alarm clock I sent them last year when I went away.

'I am very fond of this clock,' he said, patting it on the back; 'it will ring for me any morning when I want to go out fishing. Bedad, there are no two clocks in the island that would be equal to it.'

I had some photographs to show them that I took here last year, and while I was sitting on a little stool near the door of the kitchen, showing them to the family, a beautiful young woman I had spoken to a few times last year slipped in, and after a wonderfully simple and cordial speech of welcome, she sat down on the floor beside me to look on also.

The complete absence of shyness or self-consciousness in most of these people gives them a peculiar charm, and when this young and beautiful woman leaned across my knees to look nearer at some photograph that pleased her, I felt more than ever the strange simplicity of the island life.

Last year when I came here everything was new, and the people were a little strange with me, but now I am familiar with them and their way of life, so that their qualities strike me more forcibly than before.

When my photographs of this island had been examined with immense delight, and every person in them had been identified--even those who only showed a hand or a leg--I brought out some I had taken in County Wicklow. Most of them were fragments, showing fairs in Rathdrum or Aughrim, men cutting turf on the hills, or other scenes of inland life, yet they gave the greatest delight to these people who are wearied of the sea.

[やぶちゃん注:「皮砥」(原文“strop”)は「かわと」と読み、床屋で見かけるような剃刀を研ぐための革に研磨剤を塗りこんだものをいう。

「ウィクロー郡」“County Wicklow”。ウィックロー州のこと。アイルランド東部中央、レンスター地方の州。ダブリン州の南に位置する。

「ラスドラム」“Rathdrum”(ゲール語“Ráth Droma”)はウィックロー州の南東のやや内陸に位置する村。

「オーリム」“Aughrim”(ゲール語“Eachroim”)ラスドラムの南西10キロ程の位置にあるウィックロー州の小さな町。]

今年見る島の生活は一層暗黑である。太陽は滅多に照らず。來る日も來る日も、冷い西南の風は霰交りの時雨や厚い雲の群れを伴つて、斷崖を越えて吹き荒ぶ。

島に居る息子たちは、可成穏やかな日はいつも朝の三時頃から釣に出てゐる。それでも魚が多くないので、儲けがない。

老人も長い釣竿や撒き餌を持つて釣に行くが、これは更に不漁である。

天氣が全く惡くなると、漁はやめてしまつて、老人も息子たちも雨の中を馬鈴薯掘りに出て行く。女たちは時時、彼等の手助けをするが、不斷の仕事は牛の世話をしたり、家に居て糸を紡いだりする事である。

今年は家の中が何んとなく活氣がない。三人の息子がゐないからである。マイケルは本土へ、昨年キルロナンで働いてゐたもう一人の息子は合衆國へ行つてしまつた。

昨日、マイケルから母親へ宛てて手紙が來た。それは英語で書いてあつた。愛蘭土語で讀み書きの出來るのは家では彼一人だけであつたからである。私は部屋に居ながら、それが徐ろに拾ひ讀まれ、翻譯されてゐるのを聞いてゐた。少したつて、お婆さんはそれを讀んでくれと、私の處へ持つて來た。

マイケルは最初に仕事の事、貰つてゐる賃金の事を云ひ、それから或る晩、街を歩ゐてゐて、往來で上を仰いで、此の島の「砂の岬」の夜は如何に雄大であらうと、一人想ひ出したと云ひ、――淋しくまた悲しく感じたためではないと附け加へてあつた。終りの方で、日曜の朝、私と逢つた有樣を傳説もどきの誇大さで長長と述べ、そして「私たちは二三時間、實に愉快に話しましたよ。」とあつた。私が彼にやつたナイフに就いて書き、島では誰も「こんなのを見た者はなかつた」ほど立派であつたとあつた。

此間はアメリカに居る息子から手紙が來た。それには、腕に一寸怪我をしたが、又よくなつた こと、ニューヨークを去つて、二三百哩奧の方へ行かうとしてゐることが書いてあつた。

お婆さんはその後で一晩中、襟卷を頭から被つて、つつましく泣唱をしながら、爐邊の椅子に腰掛けてゐた。アメリカは遠いとは云つても結局、大西洋の向ふ岸に過ぎないと彼女は思つてゐたやうである。併し今、鐵道の話とか、海のない内地の都會の話とか彼女に了解の出來ない事を聞くと、自分の息子は永久に行つてしまつたと、しみじみ思へるのである。彼女は、去年しばしば家の後の石垣に腰掛けては、息子の乘つて働いてゐる漁船がキルロナンを出て、瀨戸に迫つて來るのをぢつと眺めてゐるのが常であつたとか、またそのやうにして皆出て來ると、いつもどんな仲間があつたかを、彼女はよく私に語つた。

母親の感情は島では非常に強く、それがため女たちは苦痛の一生を與へられる。息子たちは成長して丁年になつたと思ふと居なくなるか、或は此處で海上の絶えざる危險の中で生活する。娘たちもまた出て行つてしまふか、或は大きくなればやがてその順番に彼女たちを苦しめる子供を育てるために、その青春時代に疲れ果てる。

*

This year I see a darker side of life in the islands. The sun seldom shines, and day after day a cold south-western wind blows over the cliffs, bringing up showers of hail and dense masses of cloud.

The sons who are at home stay out fishing whenever it is tolerably calm, from about three in the morning till after nightfall, yet they earn little, as fish are not plentiful.

The old man fishes also with a long rod and ground-bait, but as a rule has even smaller success.

When the weather breaks completely, fishing is abandoned, and they both go down and dig potatoes in the rain. The women sometimes help them, but their usual work is to look after the calves and do their spinning in the house.

There is a vague depression over the family this year, because of the two sons who have gone away, Michael to the mainland, and another son, who was working in Kilronan last year, to the United States.

A letter came yesterday from Michael to his mother. It was written in English, as he is the only one of the family who can read or write in Irish, and I heard it being slowly spelled out and translated as I sat in my room. A little later the old woman brought it in for me to read.

He told her first about his work, and the wages he is getting. Then he said that one night he had been walking in the town, and had looked up among the streets, and thought to himself what a grand night it would be on the Sandy Head of this island--not, he added, that he was feeling lonely or sad. At the end he gave an account, with the dramatic emphasis of the folk-tale, of how he had met me on the Sunday morning, and, 'believe me,' he said, 'it was the fine talk we had for two hours or three.' He told them also of a knife I had given him that was so fine, no one on the island 'had ever seen the like of her.'

Another day a letter came from the son who is in America, to say that he had had a slight accident to one of his arms, but was well again, and that he was leaving New York and going a few hundred miles up the country.

All the evening afterwards the old woman sat on her stool at the corner of the fire with her shawl over her head, keening piteously to herself. America appeared far away, yet she seems to have felt that, after all, it was only the other edge of the Atlantic, and now when she hears them talking of railroads and inland cities where there is no sea, things she cannot understand, it comes home to her that her son is gone for ever. She often tells me how she used to sit on the wall behind the house last year and watch the hooker he worked in coming out of Kilronan and beating up the sound, and what company it used to be to her the time they'd all be out.

The maternal feeling is so powerful on these islands that it gives a life of torment to the women. Their sons grow up to be banished as soon as they are of age, or to live here in continual danger on the sea; their daughters go away also, or are worn out in their youth with bearing children that grow up to harass them in their own turn a little later.

[やぶちゃん注:「愛蘭土語で讀み書きの出來るのは家では彼一人だけであつたからである。私は部屋に居ながら、それが徐ろに拾ひ讀まれ、翻譯されてゐるのを聞いてゐた。少したつて、お婆さんはそれを讀んでくれと、私の處へ持つて來た。」というのは、この屋の一家は文盲に近いことを言っているようだ。ゲール語を話すが、ゲール語を筆写することは殆んど出来ず、従って書かれたゲール語を読むことも出来ない。英語で書かれたものは少しは読めるけれども、やはり意味はおぼつかない。だから最終的にはシングのところに回ってくるのである。

「こんなのを見た者はなかつた」は原文が“no one on the island 'had ever seen the like of her.'”であるから、厳密には例の三人称の混同から『「彼女みたような奴を見たことがある」者は誰もいないね』となる。

「マフラー」原文“shawl”。肩掛け。今なら普通に「ショール」と訳すであろう。

「泣唱をしながら」“keening”は、第一部にも出て来た“keen”の動詞形。アイルランドの習俗で死者に対して哀しみを表すために歌われる泣き叫びを伴った悲歌(エレジー)を歌うこと。

「瀨戸に迫つて來る」は原文“beating up the sound”で、この“sound”は「海峡・瀬戸」を意味する。“beat up”はこの場合、「波を蹴って乗り出す」といった意味であろうから、『息子の乘つて働いてゐる漁船がキルロナンを出て、』「瀨戸に乘り出して行く」『のをぢつと眺めてゐるのが常であつた』の方が日本語として腑に落ちる。

「またそのやうにして皆出て來ると、いつもどんな仲間があつたかを、彼女はよく私に語つた。」もやや生硬で、お婆さんの話は原文は“and what company it used to be to her the time they'd all be out.”であるから、彼女は「また、そんな風に男たちが海に出払ってしまうと、今度は誰彼といった仲間たちが彼女の相手になってくれる、といったことを話すのが常であった」という意味である。

「丁年」成人。

最後の段落は、洋の東西を問わず、母なる存在の――その母性の――永遠の宿命の哀しみを語って余りある。]

今まで二十四時間、嵐が吹いてゐた。併し私は、髮の毛が鹽で硬張つてしまふまで、斷崖の上をさまよつた。大きな水しぶきの塊が斷崖の下から舞ひ上つて來て、或る時は風と一緒になり、岸から可成り離れた處まで渦卷きながら飛んで來て落ちる。そのどれかが私の上に落ちて來るのに逢ふと、泡の白い霰に包まれて目も見えず、暫く打ち伏してゐなければならなかつた。

波は非常に大きく、一つの並はづれて大きなのが來ると見た時、目を打たれた瞬間に、私は本能的に身を交はして隱れた程であつた。

二三時間後、海の果てしない變化と混亂で心は搔き亂されて、初めの爽快は全くの落膽に變つた。

島の西南隅で、私は大勢の人が海草を搔き集めてゐるのに出逢つた。海草は今、岩に一面に附いてゐる。それは男たちの手で寄波から搔き集められ、それから若い女の一團の手で斷崖の突き出しまで運ばれる。

此の女たちは普通の

それから後の散歩の間、たいしやく鴫の一群と岩の中に棲んでゐる田雲雀の他は何も生物に逢はなかつた。

日沒頃、雲は散つて、嵐は疾風と變つた。瀬戸には眞白な飛沫を面白さうに上げながら、大波が西から押し寄せ、その上には紫色の雲が横に長く棚引いてゐた。また灣には一杯に緑の波が荒れ狂ひ、東の方には鮮かな紫と緋の色に染まつた「

此の語らざる偉大な力の世界からの暗示は大きかつた。そして風の鎭まつた眞夜中の今、私は尚感激に震へ紅潮してゐる。

*

There has been a storm for the last twenty-four hours, and I have been wandering on the cliffs till my hair is stiff with salt. Immense masses of spray were flying up from the base of the cliff, and were caught at times by the wind and whirled away to fall at some distance from the shore. When one of these happened to fall on me, I had to crouch down for an instant, wrapped and blinded by a white hail of foam.

The waves were so enormous that when I saw one more than usually large coming towards me, I turned instinctively to hide myself, as one blinks when struck upon the eyes.

After a few hours the mind grows bewildered with the endless change and struggle of the sea, and an utter despondency replaces the first moment of exhilaration.

At the south-west corner of the island I came upon a number of people gathering the seaweed that is now thick on the rocks. It was raked from the surf by the men, and then carried up to the brow of the cliff by a party of young girls.

In addition to their ordinary clothing these girls wore a raw sheepskin on their shoulders, to catch the oozing sea-water, and they looked strangely wild and seal-like with the salt caked upon their lips and wreaths of seaweed in their hair.

For the rest of my walk I saw no living thing but one flock of curlews, and a few pipits hiding among the stones.

About the sunset the clouds broke and the storm turned to a hurricane. Bars of purple cloud stretched across the sound where immense waves were rolling from the west, wreathed with snowy phantasies of spray. Then there was the bay full of green delirium, and the Twelve Pins touched with mauve and scarlet in the east.

The suggestion from this world of inarticulate power was immense, and now at midnight, when the wind is abating, I am still trembling and flushed with exultation.

[やぶちゃん注:「泡の白い霰」原文“a white hail of foam”。これは強烈な「波の花」のことである。私は冬の能登で体験したことがある。しばしば言われるような幻想的なイメージを私は持たない。強烈な体感温度(強風になるほど発生率は高まる)はそこに住む者には苛酷な生活の一齣である。

「海豹のやうに見えた」“seal-like”。「海豹」はアザラシ。

「たいしやく鴫」原文は“curlews”。チドリ目シギ科ダイシャクシギ Numenius arquata。和名は大きく下に反ったくちばしに由来。本邦にも主に春と秋の渡りの途中で旅鳥として立ち寄り、一部はそのまま越冬する。全長60cm程度。長い脚と嘴が特徴で、頭から翼までの羽毛は褐色の細かい斑模様だが、後半身は白っぽい(以上はウィキの「ダイシャクシギ」を参照した)。

「田雲雀」原文は“pipits”。スズメ目セキレイ科タヒバリ Anthus pinoletta。本邦には冬鳥として本州以南に渡来する。全長16cm程度。冬羽は頭部から背面上面が灰褐色、翼と尾が黒褐色。喉から体下面は黄白色で眉斑(びはん:眼の上にあって眉毛のように見える模様。)とアイリングは淡色。他のセキレイ類と同じく尾を上下によく振る(以上はウィキの「タヒバリ」を参照した)。

「

雨が降つてゐたのに、草草鞋で濡れた道を歩いたので、私は風邪を引いて熱が出た。

嵐は恐ろしく吹いてゐる。若し私に何か重大な事が起つたなら、私は此處で死んで、本土で誰も知らないうちに箱に釘付けにされ、濡れた岩穴の墓地の中へ下ろされ度い。

二日前、南島から一艘のカラハがやつて來た。――あちらには圍はれた入江があるので、こちらは天候に妨げられてゐる時も出かけられる――。それは醫者を探しに來たらしい。その後、彼等は歸ることが出來ないほど荒れて、恐ろしい海を東南に向つて歸つて行くのを見たのはやつと今朝であつた。

漕手の他に二人の人――大方坊さんと醫者――の乘つてゐる四挺櫂のカラハが眞先に行き、その後に南島から來た三挺櫂のカラハがついて行つた。それはもつと危險な目に會つた。こんな天氣の時、醫者を探しに來る時には坊さんも連れて行く。若し後で必要な時、坊さんを呼びに行けるかどうかわからないから。

概して、病氣は少ない。お産の時、女は慣れた助手がなくても仲間同志で時時どうにか處理する。大概の場合、うまく行くが、時に手遲れになつて、坊さんと醫者を呼びにカラハが大急ぎで出される事がある。

去年、此處に幾日か居た赤ん坊は今此處に落付いてゐる。お婆さんが息子のゐなくなつた淋しさを紛らすために此の子を養子にしたらしい。

その子はまだゲール語の二つ三つをやつと話せる位だが、今は立派に成長してゐる。その

お婆さんが私の部屋へ爐の泥炭を持つてはひつて來る時はいつでも、彼はその後から、芝土を兩方の小脇に抱へておごそかにはひつて來て、それを爐の後に大事に置き、それから長いペティコートをぞろぞろ引きずつて、角を廻つて急いで出て行く。

彼は家より外へ出る事はないから、島に於ける公の名をまだ貰つてゐない。併し家では通常「マイケリーン・ペッグ」(即ち、小さいマイケルちやん)と呼ばれる。

時時ぶたれることがあるが、大概の場合、お婆さんが砦の丘に棲んで長くない子供を食ふ「出齒の鬼婆」の話をして、その子の機嫌をなほす。彼は一日の半ばを冷い馬鈴薯を食べたり、濃い茶を飮んだりしてゐるが、至つて丈夫である。

*

I have been walking through the wet lanes in my pampooties in spite of the rain, and I have brought on a feverish cold.

The wind is terrific. If anything serious should happen to me I might die here and be nailed in my box, and shoved down into a wet crevice in the graveyard before any one could know it on the mainland.

Two days ago a curagh passed from the south island--they can go out when we are weather-bound because of a sheltered cove in their island--it was thought in search of the Doctor. It became too rough afterwards to make the return journey, and it was only this morning we saw them repassing towards the south-east in a terrible sea.

A four-oared curagh with two men in her besides the rowers--probably the Priest and the Doctor--went first, followed by the three-oared curagh from the south island, which ran more danger. Often when they go for the Doctor in weather like this, they bring the Priest also, as they do not know if it will be possible to go for him if he is needed later.

As a rule there is little illness, and the women often manage their confinements among themselves without any trained assistance. In most cases all goes well, but at times a curagh is sent off in desperate haste for the Priest and the Doctor when it is too late.

The baby that spent some days here last year is now established in the house; I suppose the old woman has adopted him to console herself for the loss of her own sons.

He is now a well-grown child, though not yet able to say more than a few words of Gaelic. His favourite amusement is to stand behind the door with a stick, waiting for any wandering pig or hen that may chance to come in, and then to dash out and pursue them. There are two young kittens in the kitchen also, which he ill-treats, without meaning to do them harm.

Whenever the old woman comes into my room with turf for the fire, he walks in solemnly behind her with a sod under each arm, deposits them on the back of the fire with great care, and then flies off round the corner with his long petticoats trailing behind him.

He has not yet received any official name on the island, as he has not left the fireside, but in the house they usually speak of him as 'Michaeleen beug' (i.e. 'little small-Michael').

Now and then he is slapped, but for the most part the old woman keeps him in order with stories of 'the long-toothed hag,' that lives in the Dun and eats children who are not good. He spends half his day eating cold potatoes and drinking very strong tea, yet seems in perfect health.

[やぶちゃん注:「草草鞋」“pampooties”第一部で既出。『まだ鞣さない牛皮で造つた一種のスリッパ或は草鞋』と割注があった。

「醫者を探しに來る時には坊さんも連れて行く」――Priest and the Doctor――これは笑話でも冗談でもない。これがアランの自然の厳然たる掟なのだ。]

マイケルから愛蘭土語の手紙が來た。それを文字通りに譯してみよう。

親愛なる旦那樣、――あなたが汽船で出かけた時、私の父の家の方へ向はれたと聞き、此の手紙を喜びと誇りを以つて書きます。立派なゲーリック聯盟が出來ませうから、あなたは淋しくないだらうと思ひます。そして非常に勉強なさるでせう。

朝から晩まで、あなた自身の他誰も一緒に歩く人がないでせう。大へんお氣の毒です。

私の母、三人の兄弟、姉妹はどんな風にしてゐますか、色白のマイケルや、あの赤ん坊やお婆さん、ローリーを忘れないで下さい。私はすべての友達や親類の人たちを忘れかけてゐます。――御機嫌よく……

皆の名を擧げて家族の人たちを賴んだ後で、忘れ勝ちを自ら責めてゐるのはをかしい。察するところ、彼は初期の懷郷病が癒えて來て、獨立した安泰を肉親への反逆と考へたらしい。

手紙が私に持つて來られた時、マイケルの友達が一人茶の間に居た。私が讀み終へると、彼は老人の望みによつて、それを聲高に讀み上げた。最後の文に來た時、彼は一寸躊躇して全然それを省いた。

此の青年はその所有の「コンノートの戀歌」といふ一本を私の所へ持つて來てゐたのである。私はその中のどれかを讀んでくれ、成るべくなら歌つてくれと云つた。その内の二つを讀んでもらつて見ると、その内の多くはお婆さんの子供の時から知つてゐるものであつた。尤も彼女の知つてゐるのは本に書いてあるのとは時時ちがつてゐたが。彼女は羊毛を染めてゐる藍壺の傍の爐邊の椅子に腰掛けて、體を搖すぶつてゐた。そして靑年が讀み終へると、彼女は再びそれを取り上げて、憂鬱や歡喜を聲に籠めながら、微妙な音樂的な節で歌ふのであつた。それは、非常に深遠な詩にこもつてゐるあらゆる抑揚を聲に附けるやうであつた。

ランプは暗く

*

An Irish letter has come to me from Michael. I will translate it literally.

DEAR NOBLE PERSON,--I write this letter with joy and pride that you found the way to the house of my father the day you were on the steamship. I am thinking there will not be loneliness on you, for there will be the fine beautiful Gaelic League and you will be learning powerfully.

I am thinking there is no one in life walking with you now but your own self from morning till night, and great is the pity.

What way are my mother and my three brothers and my sisters, and do not forget white Michael, and the poor little child and the old grey woman, and Rory. I am getting a forgetfulness on all my friends and kindred.--I am your friend ...

It is curious how he accuses himself of forgetfulness after asking for all his family by name. I suppose the first home-sickness is wearing away and he looks on his independent wellbeing as a treason towards his kindred.

One of his friends was in the kitchen when the letter was brought to me, and, by the old man's wish, he read it out loud as soon as I had finished it. When he came to the last sentence he hesitated for a moment, and then omitted it altogether.

This young man had come up to bring me a copy of the 'Love Songs of Connaught,' which he possesses, and I persuaded him to read, or rather chant me some of them. When he had read a couple I found that the old woman knew many of them from her childhood, though her version was often not the same as what was in the book. She was rocking herself on a stool in the chimney corner beside a pot of indigo, in which she was dyeing wool, and several times when the young man finished a poem she took it up again and recited the verses with exquisite musical intonation, putting a wistfulness and passion into her voice that seemed to give it all the cadences that are sought in the profoundest poetry.

The lamp had burned low, and another terrible gale was howling and shrieking over the island. It seemed like a dream that I should be sitting here among these men and women listening to this rude and beautiful poetry that is filled with the oldest passions of the world.

[やぶちゃん注:「立派なゲーリック聯盟が出來ませうから」少し後に出て来るが、イニシマーン島には既にゲール語連盟の支部が置かれている。それを指す。

「コンノートの戀歌」“Love Songs of Connaught”(「コナハトの恋愛歌集」)は、古代ゲール語学者、ゲール語連盟・アイルランド民俗学協会(“the

Folklore of Ireland Society”)の設立者にして後の初代アイルランド共和国大統領Douglas Hyde(Dubhighlas

de Hide ダグラス・ハイド 1860年~1949年)が1893年に出版したもの。ゲール語の民話民謡を収録、英訳をつけたもので、アイルランド文芸復興運動に於ける画期的な作品とされる。菱川英一氏の「Oireachtas na Gaeilge エラハタス・ナ・ゲールゲ」(アイルランド語の全国祭典)の概説の中には、イェーツが同書に付された英語訳に対して、'the coming of a new power into language'「新しい力が言語に到来した」と述べた、という記載がある。]

馬は此の二三日來、コニマラに於ける夏の馬草食ひから歸りつつある。それは去年、牛が船積みされた砂濱に陸上げされる。私は今朝早く、その波の中に到着するのを見に下りて行つた。漁船は岸から少し離れて碇泊してゐたが、叫んだり、繩で叩いたりしてゐる男たちに取圍まれた一匹の馬が船緣に立つてゐるのが見えた。やがて、馬が海中に飛び込むと、カラハの中で待つてゐた幾人かの男は端索で馬を捕へて、寄波から二十ヤード以内の所まで引張つて行つた。それからカラハは漁船へ戻つて行き、馬はひとりで陸の方へ向つて進んで來るやうに後に殘された。

私が立つてゐると、一人の男が私の所へやつて來て、いつものやうに挨拶をした後で尋ねた――

「旦那、此の頃どこかで戰爭があるかね?」

私はトランスヴァールに何か騷動があるらしいと云つたが、次の馬が波に近づいて來たので、歩を移して、その人と別れた。

それから後、波止場まで海の緣を歩いて行つた。其處には最近、澤山の泥炭が運び込まれてあつた。それは通常、暫くの間、砂山の上に積み置かれ、それから籠に入れられ、島の驢馬或は馬の脊に吊られた籠に入れられて家へ運び上げられる。

此の數週間、村人はそれに忙しく、村から波止場へ行く道は、後から驢馬を追つて行く子供、或は籠の

*

The horses have been coming back for the last few days from their summer's grazing in Connemara. They are landed at the sandy beach where the cattle were shipped last year, and I went down early this morning to watch their arrival through the waves. The hooker was anchored at some distance from the shore, but I could see a horse standing at the gunnel surrounded by men shouting and flipping at it with bits of rope. In a moment it jumped over into the sea, and some men, who were waiting for it in a curagh, caught it by the halter and towed it to within twenty yards of the surf. Then the curagh turned back to the hooker, and the horse was left to make its own way to the land.

As I was standing about a man came up to me and asked after the usual salutations:--

'Is there any war in the world at this time, noble person?' I told him something of the excitement in the Transvaal, and then another horse came near the waves and I passed on and left him.

Afterwards I walked round the edge of the sea to the pier, where a quantity of turf has recently been brought in. It is usually left for some time stacked on the sandhills, and then carried up to the cottages in panniers slung on donkeys or any horses that are on the island.

They have been busy with it the last few weeks, and the track from the village to the pier has been filled with lines of red-petticoated boys driving their donkeys before them, or cantering down on their backs when the panniers are empty.

[やぶちゃん注:底本では次の段落と繋がっているが、原文では行空けがあるので、ここで切った。

「二十ヤード」1yardは約0.9mであるから、凡そ18m。

「端索」は「はづな」と読ませているものと思われる。原文は“bits of rope”。馬の馬の

「トランスヴァールに何か騷動があるらしい」シングの第二回目のアラン島訪問は栩木氏によれば、1899年9月12日から10月7日であるから、これはイギリスとオランダ系ボーア人(アフリカーナー)が南アフリカに於ける植民地化を争った“Boer

War”第二次ボーア戦争勃発直近のキナ臭さを言っている。「トランスヴァール」」はトランスヴァール共和国のことで、当時、現在の南アフリカ共和国北部にあるヴァール川北方に存在した1852年ボーア人によって建国された国家で、首都はプレトリア。第二次ボーア戦争(Second

Boer War)は独立ボーア人共和国であったオレンジ自由国及びトランスヴァール共和国と大英帝国の間に1899年10月11日から1902年5月31日の間に発生した。長期の激戦の末に二共和国は敗北、大英帝国に吸収された(以上はウィキの「ボーア戦争」を参照した)。

「次の馬が波に近づいて來たので」原文は“and then another horse came near the waves”で、確かに「波」であるがどうもしっくりこない。“wave”は古語及び詩語で[the ~(s)]の形で》水・川・湖・海全般を表すので、ここは波がうち寄せる「波打ち際」と訳した方がよかろう。直後のシーンを見てもそうとしか読めない。]

これ等の男女はどことなく私から妙にかけ離れてゐるやうである。彼等とても私と同じやうな、また動物と同じやうな感動を持つてゐる。然るに、私は彼等と話すことの澤山ある時でも、山の霧の中で私の傍で悲しげに吠える犬に向つてゐると同じやうに話しかけることが出來ない。

彼等と一時間も表にゐると、得體の知れない想像が突然浮んで來て、それからまた彼等にも私にも親しみのある漠然たる感動が突然起つて來るのを感ぜずにはゐられない。或る時は、私は此の島を申し分のない家庭または安息所と思ふこともあるが、また或る時は、自分は此の人たちの中で

夕方時時、一人の少女に逢ふ。その少女はまだ十五六にもならないが、或る點では此處で逢つた誰よりも自覺的に發達してゐる。彼女は生涯の或る期間を本土で暮らした。そしてゴルウェーで見た幻滅は彼女の想像をひがませてしまつた。

爐邊で向き合はせに腰掛けてゐる時、彼女の聲は同じ文句の中で、或は子供のやうな調子に、或は悲しみに疲れた古い民族の沈んだ調子に變るのを私は聞く。或る時は彼女は單なる百姓であるが、或る時は有史以前の幻滅感を以つて世界をぢつと眺めてゐるやうである。その灰色がかつた碧い目の表情には、雲や海の希望のないあらゆる外部の姿を宿してゐる。

私たちの會話は常にまとまりがない。或る晩、本土の或る町に就いて語つた。

「ああ、をかしな處だわ。」彼女は云つた。「あんな處に住みたくないわ。本當にをかしな處だわ。でも、をかしくない處つてあるかしら。」

また他の晩は現在島に居る人のこと、また訪ねて來る人のことを語つた。

「お父さん――死んぢやつたわ、」彼女は云つた。「親切な人だつたけれど、をかしな人だつたわ。坊さんもをかしな人たちばかりだわ。をかしくない人つてあるかしら。」

それから長い間、默つてゐた後で、彼女にも不思議であり、私にも不思議であるに相違ないことを語るかのやうに眞顏になつて、自分は男の子が大へん好きだと云つた。

此のやうにしばしば子供らしい無邪氣なありのままの話をしながら、彼女は常に感情的に熱心に、まちがつてない事を愛嬌よく言はうとする。

或る晩、彼女が、普通の爐のある宿の脇部屋で、火をつけようとしてゐるのを見かけた。私は手傳ひをしようと中にはひつて、風道を作るには爐の口に紙をかう當てがふのだと、彼女の全く知らなかつた方法を教へた。それからパリーでは、人に邪魔されないやうにただ獨りで暮らし、自分で火を起す人がゐるといふ話をした。彼女は泥炭を見詰めながら、床下に脊を丸くして坐つてゐたが、その話を聞くと驚いたやうに顏を上げた。

「その人たちは私に似てゐるわ。」彼女は云つた。「誰だつてそんなことを考へたくなるわ。」

同情の下に、二人の間にはまだ溝のあるのを感じる。

「ねえ、」と彼女は、今晩私が彼女と別れようとする時、口籠つて云つた。「あなたは今に地獄へ行くと思ふわ。」

時時、或る家の茶の間でも彼女に逢ふ。其處には日が暮れると若い男たちがトランプをしに行く。そして女の子もこつそり行つてはそれに加はる。そんな時、彼女の目は蠟燭の光に輝き、顏は青春の最初の喜びで紅潮して、毎晩、炭火に當りながらのらくらしてゐる彼女とは見えないまでになる。

*

In some ways these men and women seem strangely far away from me. They have the same emotions that I have, and the animals have, yet I cannot talk to them when there is much to say, more than to the dog that whines beside me in a mountain fog.

There is hardly an hour I am with them that I do not feel the shock of some inconceivable idea, and then again the shock of some vague emotion that is familiar to them and to me. On some days I feel this island as a perfect home and resting place; on other days I feel that I am a waif among the people. I can feel more with them than they can feel with me, and while I wander among them, they like me sometimes, and laugh at me sometimes, yet never know what I am doing.

In the evenings I sometimes meet with a girl who is not yet half through her teens, yet seems in some ways more consciously developed than any one else that I have met here. She has passed part of her life on the mainland, and the disillusion she found in Galway has coloured her imagination.

As we sit on stools on either side of the fire I hear her voice going backwards and forwards in the same sentence from the gaiety of a child to the plaintive intonation of an old race that is worn with sorrow. At one moment she is a simple peasant, at another she seems to be looking out at the world with a sense of prehistoric disillusion and to sum up in the expression of her grey-blue eyes the whole external despondency of the clouds and sea.

Our conversation is usually disjointed. One evening we talked of a town on the mainland.

'Ah, it's a queer place,' she said: 'I wouldn't choose to live in it. It's a queer place, and indeed I don't know the place that isn't.'

Another evening we talked of the people who live on the island or come to visit it.

'Father is gone,' she said; 'he was a kind man but a queer man. Priests is queer people, and I don't know who isn't.'

Then after a long pause she told me with seriousness, as if speaking of a thing that surprised herself, and should surprise me, that she was very fond of the boys.

In our talk, which is sometimes full of the innocent realism of childhood, she is always pathetically eager to say the right thing and be engaging.

One evening I found her trying to light a fire in the little side room of her cottage, where there is an ordinary fireplace. I went in to help her and showed her how to hold up a paper before the mouth of the chimney to make a draught, a method she had never seen. Then I told her of men who live alone in Paris and make their own fires that they may have no one to bother them. She was sitting in a heap on the floor staring into the turf, and as I finished she looked up with surprise.

'They're like me so,' she said; 'would anyone have thought that!'

Below the sympathy we feel there is still a chasm between us.

'Musha,' she muttered as I was leaving her this evening, 'I think it's to hell you'll be going by and by.'

Occasionally I meet her also in the kitchen where young men go to play cards after dark and a few girls slip in to share the amusement. At such times her eyes shine in the light of the candles, and her cheeks flush with the first tumult of youth, till she hardly seems the same girl who sits every evening droning to herself over the turf.

[やぶちゃん注:「アラン島」の中でも魅力に満ちた登場人物(シングと少女)がくっきりと見える印象的なシークエンスである。

「然るに、私は彼等と話すことの澤山ある時でも、山の霧の中で私の傍で悲しげに吠える犬に向つてゐると同じやうに話しかけることが出來ない。」原文は“yet I cannot talk to them when there is much to say, more than to the dog that whines beside me in a mountain fog.”で、ここは「然るに、私は彼等と話すことの澤山ある時でも、山の霧の中で私の傍で悲しげに吠える犬に向つてゐると同じ『程度にしか』話しかけることが出來ない。」としないと日本語としては通じない。

「

「お父さん――死んぢやつたわ、」は原文“'Father is gone,'”であるが、これは続く“'he was a kind man but a queer man. Priests is queer people, and I don't know who isn't.'”という彼女の台詞の“Priest”(司祭・聖職者)との連関から、“Father”は「父」ではなく「神父」であることが分かる。またこれが「現在島に居る人のこと、また訪ねて來る人のことを語つた」内容であるからには、“is gone,”を「死んぢやつたわ、」と訳すのは如何か? この教区での勤めを終えて島から去って行った神父のことであろう。

「彼女は常に感情的に熱心に、まちがつてない事を愛嬌よく言はうとする。」は原文は“she is always pathetically eager to say the right thing and be engaging.”であるが、やはりやや日本語としては「まちがつてない」のだが、如何せん、意味がとり難い。「彼女は常に――感動的と言ってもいいほど――頻りに――正しく且つ魅力的な言い方をしようと努めている。」といった感じであろう。

「風道」“draught”。「かざみち」と読んでいよう。火おこしのための空気の通り道。

「同情の下に、二人の間にはまだ溝のあるのを感じる」理由は直前だけでなく、次の少女の「地獄」の発言をも受けての謂いであろう。]

ゲーリック聯盟の支部は、私の此の前の訪問以來、此處に開かれてゐる。毎日曜の午後、三人の女の子が女の會合の初まると云ふ合圖のよく響く手鈴を鳴らしながら、村を通つて行く。――此處では時刻が認められてゐないから、時間を決めても無益であらう。

その後直ぐに、幾組もの少女たち――五歳から廿五歳までのあらゆる年齡の少女たち――が眞赤な晴着のペティコートを着て續々と校舍の方へ行き初める。これ等の若い女たちがゲール語をただ何となく尊敬してゐるといふ他に何等の理由もなく、自由な午後を自ら進んで綴字法といふ骨の折れる勉強に費すと云ふことは注意すべきことである。さういつた尊敬は、大部分近頃の訪問者たちの影響に依るのは事實であるが、彼等がさういつた影響を痛切に感じてゐる事實は、それだけで興味あることである。

現在の言語運動の影響がなかつたもつと昔の時代は、ゲール語に對する特別な愛着があつたとは思へない。彼等は、子供に出世する能力を與へるために、出來る時はいつでも英語で話をする。青年たちでさへ私にこんなことを云ふことがある。――

「あなたはむづかしい英語ができます。私も本當にあなたのやうになりたいです。」

言葉のことに關しては、女は大いに保守的な役目を持つ。彼女たちは學校で、或は兩親から英語を少し教はつたが、此の島生れの人以外と話す機會が滅多にない。それで外國語の知識は依然として初歩のままである。此の家でも、豚や犬に物を云ふ時か、或は女の子が英語の手紙を讀む時以外に、女から英語を一言も聞いたことがない。併しもつと積極的な性格を持つてゐる女は、明かに同じ境遇にありながら、非常な流暢さに達することが屢々ある。例へば此處へ時時、訪ねて來る宿の婆さんの一人の親戚のやうな場合である。

私が時時、立ち寄つてみる男の學校では、子供たちの英語の知識に感心させられる。尤も彼等は自分たち同志では、常に愛蘭土語で話すが。學校そのものはひどく吹き曝らしの中にある不愉快な建物である。朝、寒い日には、子供たちは泥炭の一片を書物と一緒に結び付けて登校する。それは火をよく保たせるための割當である。併し、やがて現代的の設備が施されるに違ひない。

*

A branch of the Gaelic League has been started here since my last visit, and every Sunday afternoon three little girls walk through the village ringing a shrill hand-bell, as a signal that the women's meeting is to be held,--here it would be useless to fix an hour, as the hours are not recognized.

Soon afterwards bands of girls--of all ages from five to twenty-five--begin to troop down to the schoolhouse in their reddest Sunday petticoats. It is remarkable that these young women are willing to spend their one afternoon of freedom in laborious studies of orthography for no reason but a vague reverence for the Gaelic. It is true that they owe this reverence, or most of it, to the influence of some recent visitors, yet the fact that they feel such an influence so keenly is itself of interest.

In the older generation that did not come under the influence of the recent language movement, I do not see any particular affection for Gaelic. Whenever they are able, they speak English to their children, to render them more capable of making their way in life. Even the young men sometimes say to me--

'There's very hard English on you, and I wish to God I had the like of it.'

The women are the great conservative force in this matter of the language. They learn a little English in school and from their parents, but they rarely have occasion to speak with any one who is not a native of the islands, so their knowledge of the foreign tongue remains rudimentary. In my cottage I have never heard a word of English from the women except when they were speaking to the pigs or to the dogs, or when the girl was reading a letter in English. Women, however, with a more assertive temperament, who have had, apparently, the same opportunities, often attain a considerable fluency, as is the case with one, a relative of the old woman of the house, who often visits here.

In the boys' school, where I sometimes look in, the children surprise me by their knowledge of English, though they always speak in Irish among themselves. The school itself is a comfortless building in a terribly bleak position. In cold weather the children arrive in the morning with a sod of turf tied up with their books, a simple toll which keeps the fire well supplied, yet, I believe, a more modern method is soon to be introduced.

[四挺漕ぎカラハ]

私はまた北島に來て、特殊な感じを以つて瀨戸越しに斷崖の方を眺めてゐる。南の方に見えるあの小屋の中で、大昔の詩や傳説にある不思議な生活をしてゐる人たちが澤山住んでゐようとはどうしても思へない。その人たちと較べて、此の島の繁榮から起る墮落は甚だ慨かはしいことである。あちらの人たちの鳥や花も共に持つ魅力は、こちらでは儲けに熱中してゐる人の心配に代つてゐる。顏は同じやうでも、目や顏付が違ふ。此處では子供でさへイニシマーンの人にない現代的の特徴を何となく持つてゐるやうに見える。

私の中の島からの航海はひどかつた。朝非常に荒れてゐたので、普通の事情ならば渡る計畫はしなかつたのであるが、教區僧――イニシマーンに駐在してゐる――の處へ來たカラハで渡る準備がしてあつたので、後へ退きたくなかつた。

その朝外へ出て、いつものやうに斷崖の上に登つた。出逢つた數人の男は、私が出かけようとしてゐることを云ふと、首を振つて瀨戸は汐のためにカラハが渡れるかどうかを怪しんだ。

宿の方へ戻つて行く時、南の島から今丁度渡つて來た副牧師を見かけたが、嘗つて經驗した事のない惡い航海をしたのであつた。 「

汐は二時には變る筈であつた。その後は風や波は同じ方向からやつて來るので、海もいくらか靜まるだらうと思はれた。午前中、私たちは茶の間に腰掛けてゐた。人人は絶えずほひつて來て、船は出したものかどうか、海の何處が最も荒れてゐるかと彼等の意見を云ひに來た。

遂に出かけることに決め、石垣に吠える風交りに雨の降りしきる中を、私は波止場に向つて出發した。一緒に行く筈であつた學校の先生と僧侶は、私が村を通つて行くと、出て來て渡らない方がよいと忠告してくれた。併し船頭たちは海の方へ進んで行くし、私はその後を追つた方がよいと考へた。家の一番上の息子も一緒に來てゐる。わかりきつた危險があるなら、私よりも汐の事はよく知つてゐる爺さんが、息子をよこす事はないだらうと考へた。

船頭たちは、村の下の高い石垣の下で私を待つてゐた。私たちは共共に進んで行つた。島がこんなに荒れはてて見えた事は未だかつてなかつた。降りしきる雨を通して、黑ずんだ岩越しに波の荒狂つてゐる灣の方を眺めると、云ひ知れぬ心細さが私を襲つて來た。

爺さんは恐怖の利益に就いて彼の意見を私に與へてくれた。

「海を怖がらない男は直ぐ溺れるだらう。」彼は云つた。「何故つて、出か【け】てはならない日に出かけて行くからね。だが、こちとらは海を怖がるんだ。だから、こちとらは、たまに溺れるばかりさ。」

近所の人たちの小人數の群が、私を見送りに下の方に集つてゐた。砂丘を越える時、風よりも高く聲を出さうと、互ひに叫び合はなければならなかつた。

船頭たちはカラハを運び下ろして來て、波止場の風下に立ち、紐のある帽子を被つたり、合羽を着たりした。

彼等が櫂の緊紐、櫂栓[櫂を船緣に固定せしめる釘]その他カラハの中の色色な物を檢査する事は、これまでに見た事もないほど丁寧であつた。それから私の鞄が吊り入れられ、支度が出來た。船頭四人のほかに此の島へ渡りたいといふ一人の男が、私たちと共に行かうとしてゐた。彼が船首に這ひ上らうとすると、一人の老人が群の中から進み出た。

「その男を連れて行くな。」彼は云つた。「先週、クレアに連れて行つたが、皆んなすんでの所で溺れる所だつた。此の間はイニシールに行つたが、カラハのあばら三枚を壞して戻つて來た。此の三つの島にとつてこんな不吉な男はありやしない。」

「畜生! 何云つてやがるんだい。」とその男は答へた。

私たちは出發した。カラハは四人漕で、船尾はその男に殘すやうに、私には最後の席があてがはれた。その男は船尾の船緣にある特別の櫂栓で、他の櫂と直角に動く櫂で舵を取つた。

百ヤードぐらゐ行つた頃、船首に帆を一枚擧げた。それで速さが著しく加はつた。

驟雨は過ぎ、風は鎭まつたが、大きな素晴らしくキラキラする波が私たちの方向の眞横に落ちかかつてゐた。

舵取りが急に櫂を引いて船を廻はす度に、船首は高く上つて、それから次の谷へザンブとばかり飛沫を上げながら、落ち込んで行つた。此のやうであつたから、船尾も代る代る投げ上げられ、櫂を放して兩手で船緣にしがみ付いてゐる舵取と私は共に海の上高く上げられた。

波が去つて、もとの方向にかへり、遮二無二數ヤードを漕ぐと、また同じやうな動作を繰り返へさなければならなかつた。やつとのことで瀨戸へ出て行くと、違つた種類の波に逢ひ初めた。それは或る距離の間に他の波よりぬきん出て高く見えた。

その波の一つが見え出すと、最初の努力はその範圍内から一生懸命に出ることであつた。舵取りはゲール語で「シゥーアル、シゥーアル」(走れ走れ)と呼び出した。時時、その群が恐ろしい速さでこちらへ押寄せて來ると、その聲は金切り聲となつた。すると漕手までそれに合はせて叫んだ。そして波が後の方へ過ぎて行くか、船緣にどつと碎けるまで、カラハは暴れ狂ふ獸が跳んだり震へたりするやうであつた。

此の波と競走してゐる時こそ主な危險のある時であつた。波を避けられたら、さうする方がよいのであるが、若し逃げようとしてゐる間に追ひつかれて舟の横腹にぶつけられたら、沈沒は必然であつた。舵取りは此の役目に張切つて震へてゐるのがよくわかつた。何故なら、若し彼の判斷に誤りがあつたら、私たちは顚覆したであらうから。

私たちは一度、危機一髮を逃れた。一つの波は他の波より遙かに高いやうに見えた。例の如く激しい努力の一瞬時があつた。それも無駄であつた。忽ち波はこちらへ襲ひかかつて來るやうに見えた。舵取りは憤然と叫び聲を上げながら、それを迎へようと櫂で舳先を向けるのに一生懸命であつた。波が周りに碎け、迸り流れた時、彼は殆んど成功した。私は恰かも結んだ繩で背中を打たれたかのやうに感じた。白い泡は私の膝や目の邊りに

カラハが間にはさまれ、もとの狀態に戻るひまがない程にいくつかの波が一緒に密集してやつて來た時、何度も危險な作業をやつたけれども、その時が最も危い時であつた。騎手や泳ぎ手の命が時にはその兩手にあるやうに、私たちの命もその男たちの手腕と勇氣に任せてあつた。そしてこの爭鬪の興奮は餘り激しかつたので、怖いと思ふひまもなかつた。

私は渡船の樂しみを味つた。男たちの動作で傾いたり震へたりする此の淺い布の

*

I am in the north island again, looking out with a singular sensation to the cliffs across the sound. It is hard to believe that those hovels I can just see in the south are filled with people whose lives have the strange quality that is found in the oldest poetry and legend. Compared with them the falling off that has come with the increased prosperity of this island is full of discouragement. The charm which the people over there share with the birds and flowers has been replaced here by the anxiety of men who are eager for gain. The eyes and expression are different, though the faces are the same, and even the children here seem to have an indefinable modern quality that is absent from the men of Inishmaan.

My voyage from the middle island was wild. The morning was so stormy, that in ordinary circumstances I would not have attempted the passage, but as I had arranged to travel with a curagh that was coming over for the Parish Priest--who is to hold stations on Inishmaan--I did not like to draw back.

I went out in the morning and walked up the cliffs as usual. Several men I fell in with shook their heads when I told them I was going away, and said they doubted if a curagh could cross the sound with the sea that was in it.

When I went back to the cottage I found the Curate had just come across from the south island, and had had a worse passage than any he had yet experienced.

The tide was to turn at two o'clock, and after that it was thought the sea would be calmer, as the wind and the waves would be running from the same point. We sat about in the kitchen all the morning, with men coming in every few minutes to give their opinion whether the passage should be attempted, and at what points the sea was likely to be at its worst.

At last it was decided we should go, and I started for the pier in a wild shower of rain with the wind howling in the walls. The schoolmaster and a priest who was to have gone with me came out as I was passing through the village and advised me not to make the passage; but my crew had gone on towards the sea, and I thought it better to go after them. The eldest son of the family was coming with me, and I considered that the old man, who knew the waves better than I did, would not send out his son if there was more than reasonable danger.

I found my crew waiting for me under a high wall below the village, and we went on together. The island had never seemed so desolate. Looking out over the black limestone through the driving rain to the gulf of struggling waves, an indescribable feeling of dejection came over me.

The old man gave me his view of the use of fear.

'A man who is not afraid of the sea will soon be drowned,' he said, 'for he will be going out on a day he shouldn't. But we do be afraid of the sea, and we do only be drownded now and again.'

A little crowd of neighbours had collected lower down to see me off, and as we crossed the sandhills we had to shout to each other to be heard above the wind.

The crew carried down the curagh and then stood under the lee of the pier tying on their hats with strings and drawing on their oilskins.

They tested the braces of the oars, and the oarpins, and everything in the curagh with a care I had not seen them give to anything, then my bag was lifted in, and we were ready. Besides the four men of the crew a man was going with us who wanted a passage to this island. As he was scrambling into the bow, an old man stood forward from the crowd.

'Don't take that man with you,' he said. 'Last week they were taking him to Clare and the whole lot of them were near drownded. Another day he went to Inisheer and they broke three ribs of the curagh, and they coming back. There is not the like of him for ill-luck in the three islands.'

'The divil choke your old gob,' said the man, 'you will be talking.'

We set off. It was a four-oared curagh, and I was given the last seat so as to leave the stern for the man who was steering with an oar, worked at right angles to the others by an extra thole-pin in the stern gunnel.

When we had gone about a hundred yards they ran up a bit of a sail in the bow and the pace became extraordinarily rapid.

The shower had passed over and the wind had fallen, but large, magnificently brilliant waves were rolling down on us at right angles to our course.

Every instant the steersman whirled us round with a sudden stroke of his oar, the prow reared up and then fell into the next furrow with a crash, throwing up masses of spray. As it did so, the stern in its turn was thrown up, and both the steersman, who let go his oar and clung with both hands to the gunnel, and myself, were lifted high up above the sea.

The wave passed, we regained our course and rowed violently for a few yards, then the same manoeuvre had to be repeated. As we worked out into the sound we began to meet another class of waves, that could be seen for some distance towering above the rest.

When one of these came in sight, the first effort was to get beyond its reach. The steersman began crying out in Gaelic, 'Siubhal, siubhal' ('Run, run'), and sometimes, when the mass was gliding towards us with horrible speed, his voice rose to a shriek. Then the rowers themselves took up the cry, and the curagh seemed to leap and quiver with the frantic terror of a beast till the wave passed behind it or fell with a crash beside the stern.

It was in this racing with the waves that our chief danger lay. If the wave could be avoided, it was better to do so, but if it overtook us while we were trying to escape, and caught us on the broadside, our destruction was certain. I could see the steersman quivering with the excitement of his task, for any error in his judgment would have swamped us.

We had one narrow escape. A wave appeared high above the rest, and there was the usual moment of intense exertion. It was of no use, and in an instant the wave seemed to be hurling itself upon us. With a yell of rage the steersman struggled with his oar to bring our prow to meet it. He had almost succeeded, when there was a crash and rush of water round us. I felt as if I had been struck upon the back with knotted ropes. White foam gurgled round my knees and eyes. The curagh reared up, swaying and trembling for a moment, and then fell safely into the furrow.

This was our worst moment, though more than once, when several waves came so closely together that we had no time to regain control of the canoe between them, we had some dangerous work. Our lives depended upon the skill and courage of the men, as the life of the rider or swimmer is often in his own hands, and the excitement was too great to allow time for fear.

I enjoyed the passage. Down in this shallow trough of canvas that bent and trembled with the motion of the men, I had a far more intimate feeling of the glory and power of the waves than I have ever known in a steamer.

[やぶちゃん注:「南の方に見えるあの小屋の中で、大昔の詩や傳説にある不思議な生活をしてゐる人たちが澤山住んでゐようとはどうしても思へない。」原文は“It is hard to believe that those hovels I can just see in the south are filled with people whose lives have the strange quality that is found in the oldest poetry and legend.”で、「どうしても思へない」が意味をとり難くしている。ここは、既にアランモア島に渡ったシングが対岸のイニシマーン島の景色を眺めていると、『今、「南の方に見えるあの小屋の中」に、「大昔の詩や傳説にある」ような「不思議な生活をしてゐる人たちが」現に「澤山住んでゐ」るという事実は、私には信じ難いことに思えた』という意味である。

「あちらの人たちの鳥や花も共に持つ魅力」原文“The charm which the people over there share with the birds and flowers”。やはりやや生硬である。「あちらのイニシマーン島の人々が、(アニミスティックに)鳥や花とともに世界を共有していることの魅力」のことである。

「教區僧」“the Parish Priest”は教区を統括する司祭。

「後へ退きたくなかつた」分かり難い。“-I did not like to draw back”であるから、相乗りさせてもらう約束を既にしており、カラハの出航準備もなされている以上、礼儀として断って「先延ばしはしたくなかった」という意味で、そこにはもしかすると続く文を読んでいると、「今更、尻込みしたくはなかった」、「尻込みしたとは思われたくなかった」というシングの内心のやや意固地なニュアンスも含むのかも知れない。

「副牧師」“the Curate”は助任司祭。先の“the Parish Priest”の助手か。

「櫂の緊紐、櫂栓」原文“the braces of the oars, and the oarpins”。「緊紐」は「キンチュウ」と海事用語っぽく音読しているか、若しくは「しばりひも」と訓じているかは不明。“brace”は海事用語で「ブレース」「

『「畜生! 何云つてやがるんだい。」とその男は答へた。』は原文では“'The divil choke your old gob,' said the man, 'you will be talking.'”で、これは売り言葉に買い言葉の応酬で、『「悪魔がてめえの腐りかけたその口を永遠に塞いじまうぜ!」、その男は言った、「これ以上、てめえがその好き勝手な喋くりを続けるんなら、な。」』といった感じか。時に、この不吉な男は結局、どうしたのだろう。私は迷信深い漁師なら、この荒れ模様でもあり、この男の乗船を拒否した気がするのだ。実際、この後のシークエンスでは彼は描かれていない。姉崎氏は次の部分で「私たちは出發した。カラハは四人漕で、船尾はその男に殘すやうに、私には最後の席があてがはれた。その男は船尾の船緣にある特別の櫂栓で、他の櫂と直角に動く櫂で舵を取つた。」と、「その男」というのが、あたかもこの「不吉な男」であるかのように訳されている(私にはそうとしか読めない)が、これはおかしい。この部分は、このカラハは四人漕ぎで、漕ぎ手(「船頭」)が四人いたことは前に書いてあるからである(因みに男がもしカラハに乗船していた場合は漕ぎ手四人+シング+不吉な男で計六名になる)。従って、この部分の意味は、『その「カラハは四人漕で」あったが(イェイツの挿絵を参照されたい)、普通なら四人が総て、カラハの中に横に渡した四箇所の座席に座って漕ぐのであるが、今回は四人目の漕ぎ手が船尾の座席には座らずに、私にその「最後の席があてがはれた。」但し、私は漕ぐわけではない。「その」漕ぎ手の(「不吉な男」では断じて、ない)四人目の「男は船尾の船緣にある特別の櫂栓で、他の櫂と」異なり、「直角に動く櫂で舵を取」る役をそこ(船尾)で受け持った。』という意味であろう。もし「不吉な男」が乗船していたとすれば、最初に彼がした通り、「船首」に蹲っていたとしか考えられないのである。しかし、であればシングは、この後にやって来る恐ろしいまでのピッチングのシーンで、自分や舵取りと同じように対になったリズムで『海の上高く上られ』る、この「不吉な男」を描写しないはずがない、と私は思うのである。彼はやはり乗っていないのではなかろうか? 如何?

「迸り」は「ほとばしり」と読む。]

ムールティーン爺さんは再び私の相手になつてゐる。そして今度は私も彼の愛蘭土語を大部分了解する事が出來る。

今日、彼はクロッグハウス、即ち蜂の巣状の家の遺跡を見せに連れて行つてくれた。それは島の中央の脊近くに殘つてゐる。それを見物した後で、我々は秋の陽光と枯れかけた花の香で充ちてゐる小さな野の一隅に横になつた。その間、爺さんは、一時間以上もかかつて、私に長い傳説を語つた。

彼は目が見えないので、私は遠慮なしに彼の顏をぢつと眺められる。やがて、その顏の表情のために聞くのを忘れてしまふ。私は、乘つてゐる有史以前の石疊から、話の古代の有樣を想像しながら、日なたに夢みごこちで横になつてゐた。彼の話が意味のない段落――それは話の中でよくやる――に來ると、彼の顏は子供らしい夢中さに生き生きと輝き、私は我に歸つて彼の樂しさうに早口にしやべる間中、ぢつと傾聽した。「彼等は道を見つけて、私は溝を見つけた。彼等は溺れて、私は救はれた。今夜、私にとつてどうでもよいなら、明夜、彼等にとつてはどうでもよくなかつた。だが、その通りでなかつたとすると、彼等は古い奧齒一本を失つたに過ぎない。」――ざつとこんな意味のないお喋舌であつた。

私は彼が震へて上れない低い石垣の上へ時時彼を持ち上げてやりながら――こんな風に調子を合はせて――彼の云ふ通りの道を家の方へと導いて行く時、彼の常に取上げて飽きない話題――私の結婚觀――に彼は會話を持つて來た。

島の頂上に達した時、彼は大西洋の海原に脊を向けて立ち止まつた。

「旦那、

「ああ、ムールティーン」私は答へた。「そんなことを私に尋ねるなんてをかしいよ。一體私を何んと考へてゐるのだ?」

「なあに、旦那、私はお前さんも今に結婚するのだと思つたよ。まあ私の云ふことを聞きなさい。結婚しない男などは牡の老ぼれ驢馬と同じだよ。姉の家へ行つたり、兄の家へ行つたり、あつちへ行つては少し食べ、こつちへ來ては少し食べ、そして自分の家を持たない。まるで岩の間をうろうろしてる牡の老ぼれ驢馬のやうなものだね。」

*

Old Mourteen is keeping me company again, and I am now able to understand the greater part of his Irish.

He took me out to-day to show me the remains of some cloghauns, or beehive dwellings, that are left near the central ridge of the island. After I had looked at them we lay down in the corner of a little field, filled with the autumn sunshine and the odour of withering flowers, while he told me a long folk-tale which took more than an hour to narrate.

He is so blind that I can gaze at him without discourtesy, and after a while the expression of his face made me forget to listen, and I lay dreamily in the sunshine letting the antique formulas of the story blend with the suggestions from the prehistoric masonry I lay on. The glow of childish transport that came over him when he reached the nonsense ending--so common in these tales--recalled me to myself, and I listened attentively while he gabbled with delighted haste: 'They found the path and I found the puddle. They were drowned and I was found. If it's all one to me tonight, it wasn't all one to them the next night. Yet, if it wasn't itself, not a thing did they lose but an old back tooth '--or some such gibberish.

As I led him home through the paths he described to me--it is thus we get along--lifting him at times over the low walls he is too shaky to climb, he brought the conversation to the topic they are never weary of--my views on marriage.

He stopped as we reached the summit of the island, with the stretch of the Atlantic just visible behind him.

'Whisper, noble person,' he began, 'do you never be thinking on the young girls? The time I was a young man, the devil a one of them could I look on without wishing to marry her.'

'Ah, Mourteen,' I answered, 'it's a great wonder you'd be asking me. What at all do you think of me yourself?'

'Bedad, noble person, I'm thinking it's soon you'll be getting married. Listen to what I'm telling you: a man who is not married is no better than an old jackass. He goes into his sister's house, and into his brother's house; he eats a bit in this place and a bit in another place, but he has no home for himself like an old jackass straying on the rocks.'

[やぶちゃん注:「クロッグハウス、即ち蜂の巣状の家の遺跡」原文は“the remains of some cloghauns, or beehive dwellings,”。後半は第一部冒頭にも出てきた“beehive-like roofs”と同じである。“cloghaun”という一般名詞は検索では見当たらない(アイルランドのホテル名や橋の名としてはある)。栩木氏は「石積み住居群」と訳され、「クロッハン」(原本では「クロツハン」)とルビを振られておられる。“clogh”という文字列はゲール語で“cloch”と綴るが(アイルランドの町名から分かる)、この単語は「石」の意である。“-haun”は全くの直感でしかないが、これは“home”の語源である中世英語“hom”、その元である古英語“hām”等と関係があるか? 識者の御教授を乞う。

「私は遠慮なしに彼の顏をぢつと眺められる」原文は“He is so blind that I can gaze at him without discourtesy”。「遠慮なしに」は「不躾に」「不作法にも」の意となる。ネット上の記事によると、イギリスの社会心理学者アージルの調査によれば、現代でも通常、人が一対一で会話をする際に相手の目や顔に視線を向けるのは、会話の全時間の内、30%からせいぜい60 %で、会話中にひたすら相手を見つめ続けている場合、それは「話の内容」ではなく、「その人自身」に対して特別な好意を持っていると考えられる(ひいては相手にそう取られかねない)らしい。従って、ここは当時のヨーロッパ社会にあっても、目上の人の顔を凝っと見て話を聞くことがかなり失礼なことを受けての、シングの謂いと考えてよい。

「お喋舌」は「おしゃべり」。

「老ぼれ驢馬」“an old jackass”。“jackass”には「馬鹿・間抜け」の意が含まれる。]

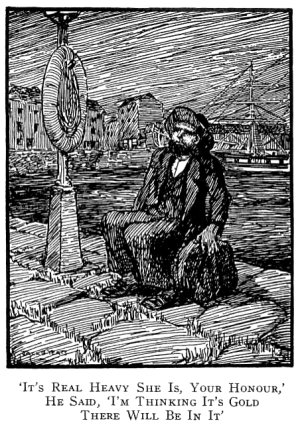

[「旦那――この娘っこは、まあ、ばかに重いなぁ。」

と彼は言った、「こん中は――金――と睨んだね。」]

私はアランを立つた。汽船は普通以上に重く荷を積んでゐたので、キルロナンを出帆したのは四時過であつた。

私は、一瞬時言ひ難い苦痛を以つて、再び三つの低い岩島が海の中へ沒するのを見た。晴れた夕方であつたので、灣に出ると、太陽は極光のやうにイニシマーンの斷崖の鋒に懸かつてゐた。

少したつと燦爛たる光は空に行き亙り、海やコニマラの山山の靑さを描き出した。

全く暗くなつてしまふと、寒さは激しくなつて來た。海の上をただ一艘だけ道を進んで行く淋しい船の上を私は歩き廻つた。乘客は私だけで、一人の舵取りの少年のほか、全部の船員は暖い機關室の中で押し合つてゐた。

三時間たつても、誰も動かなかつた。般はのろいし、舷側の寒い海の物悲しい音は全く堪へられなかつた。やがてゴルウェーの燈火が見え出した。そして船が徐ろに波止場に近づくにつれて、船員たちの姿が現はれた。

さて岸に上つてみると、私の荷物を汽車まで運んでくれる人を見つけるのに困つた。暗闇の中にやつと一人の男を見つけて、荷物を背負はせると、その男は醉拂ひであつた。私の財産もろ共に波止場の外へ轉がらないやうに氣をつけるのに苦勞した。彼は町へ出る近道に連れて行くと云つたが、壞れた建物のがらくたや船の殘骸の眞只中に來た時、彼は荷物を地面に投げ出して、その上に坐つた。

「旦那、こいつあ、ばかに重いなあ。」彼は云つた。「此の中には金がはひつてるんだらう。」

「金は一文もはひつてないよ。本だけだ。」私はゲール語で答へた。

「べダッド・イス・モール・アン・スルーアェ(ちえツ、そいつあ惜しかつた)。」彼は云つた。「金がはひつてたら、今夜、一緒にゴルウェーで馬鹿騷ぎして遊べるのだがなあ。」

半時間もかかつて、もう一度荷物を背負はせ、やつと町の方へ歩き出した。

曉遲くなつて、マイケルを訪ねるために、波止揚の方へ下りて行つた。彼の宿を取つてゐる狹い横丁に入ると、誰かが陰になつて私の後をつけて來るやうである。立ち止まつて彼の家の番號を探さうとしてゐると、私の直ぐ傍で、イニシマーン語の「フォルティエ」(いらつしやい)と云ふのを聞いた。

それはマイケルであつた。

「往來であなたを見かけましたが、」彼は云つた。「人中で話しかけるのが恥かしかつたので、後をつけて來たのです。私を覺えていらつしやるかどうかみようと。」

私たちは一緒に引返して、彼が宿へ歸らなければならない時まで町を散歩した。彼は昔の純朴さや機敏さで、相變らずであつた。併し此處の仕事が合はないので、滿足してゐない。

今夜は、ダブリンのパーネル記念祭[Ponell,Charles Stewart(1846―91)愛蘭土の自治運動の爲活動した政治家。十月六日は丁度その命日で、記念祭が行はれる。]の宵祭で、町は眞夜中に出發する汽車を待つてゐる旅客で混み合つてゐた。マイケルと別れると、私はホテルに暫く時を費し、それから鐡道の方へぶらぶら歩いて行つた。

歩廊に、島から來た幾人かの人がゐた。私はその人たちと三等車に乘り込んだ。一行の中の一人の女は姪を連れてゐたが、その人はコンノートから來た若い娘で、私の傍に腰掛けた。車の向う側に、愛蘭土語で話してゐた幾人かの老人連がをり、また水夫であつた一人の若い男がゐた。

列車が動き出すと、歩廊に物凄い歡呼の聲や叫び聲が擧り、汽車の中でさへ、男女の金切り聲を上げる者、歌を唱ふ者、仕切り壁を杖で叩く者で騷ぎは激しい。いくつかの驛で、酒場へ驅け込む突貫があつたり、行くにつれて騷ぎは愈々大きくなつた。

バリンスローでは數人の兵士が歩廊にゐて席を探してゐた。此の中の一人と私たちの仕切りにゐた水夫が口論を初め、扉がぱツと開いた瞬間に、仕切りの中はよろめく軍服や杖で一杯になつた。一寸の間騷いだ後、仲なほりが出來、兵士たちは出て行つた。兵士たちが出て行くと、連れの女たちの一團が、非常な怒りに惡口を吐きながら、露はな頭や腕を戸口へさし入れた。

少したつて、汽車が動き出すと、その女たちは狂氣のやうな泣き聲を擧げた。私は外をのぞいた。カンテラの燈に、むき出しの腕を振り上げ喚き叫んでゐる嘗つて見た事もないやうな物凄い顏や人影をちらつと見た。

夜が更けると、次の車で、女たちは大聲を上げ出した。停車場に汽車が止まつた時、卑猥な歌の言葉が聞こえた。

私たちの仕切りの中では水夫が皆を寢かせようとしない。夜中ぢゆう、滑稽味のある事、或ひは卑しげな事をしやべつたが、荒つぽい氣性をかくしながら、常に非常な雄辯であつた。

黑い上衣を着てゐた隅の老人たちは何か家傳の古物らしい物を持つてゐて、夜中ぢゆうひそひそとゲール語で話してゐた。私の傍の娘は、少したつとはにかみを捨てて、ダブリンに近づくにつれて夜明けの中に見え初めて來た田舍の地形を私にあれこれと指ささせた。彼女は木の影や、――木はコンノートには少いのである――曉の光を映し初めた堀割を喜んだ。私が何か新らしい影を教へてやる度毎に、彼女はあどけない喜びで叫んだ。――

「ああ、綺麗だこと。だけど見えないわ。」

此の私の傍の有樣は、背後で仕切り壁を搖がす亂暴さと奇妙な對照であつた。西部愛蘭土の全精神は、その妙な氣荒さや愼み深さと共に、此の一つの汽車に乘つて、東部の今は亡き政治家に最後の敬意を捧げるために、動いてゐるやうに思へた。

*

I have left Aran. The steamer had a more than usually heavy cargo, and it was after four o'clock when we sailed from Kilronan.

Again I saw the three low rocks sink down into the sea with a moment of inconceivable distress. It was a clear evening, and as we came out into the bay the sun stood like an aureole behind the cliffs of Inishmaan. A little later a brilliant glow came over the sky, throwing out the blue of the sea and of the hills of Connemara.

When it was quite dark, the cold became intense, and I wandered about the lonely vessel that seemed to be making her own way across the sea. I was the only passenger, and all the crew, except one boy who was steering, were huddled together in the warmth of the engine-room.

Three hours passed, and no one stirred. The slowness of the vessel and the lamentation of the cold sea about her sides became almost unendurable. Then the lights of Galway came in sight, and the crew appeared as we beat up slowly to the quay.

Once on shore I had some difficulty in finding any one to carry my baggage to the railway. When I found a man in the darkness and got my bag on his shoulders, he turned out to be drunk, and I had trouble to keep him from rolling from the wharf with all my possessions. He professed to be taking me by a short cut into the town, but when we were in the middle of a waste of broken buildings and skeletons of ships he threw my bag on the ground and sat down on it.

'It's real heavy she is, your honour,' he said; 'I'm thinking it's gold there will be in it.'

'Divil a hap'worth is there in it at all but books,' I answered him in Gaelic.

'Bedad, is mor an truaghé' ('It's a big pity'), he said; 'if it was gold was in it it's the thundering spree we'd have together this night in Galway.'

In about half an hour I got my luggage once more on his back, and we made our way into the city.

Later in the evening I went down towards the quay to look for Michael. As I turned into the narrow street where he lodges, some one seemed to be following me in the shadow, and when I stopped to find the number of his house I heard the 'Failte' (Welcome) of Inishmaan pronounced close to me.

It was Michael.

'I saw you in the street,' he said, 'but I was ashamed to speak to you in the middle of the people, so I followed you the way I'd see if you'd remember me.'

We turned back together and walked about the town till he had to go to his lodgings. He was still just the same, with all his old simplicity and shrewdness; but the work he has here does not agree with him, and he is not contented.

It was the eve of the Parnell celebration in Dublin, and the town was full of excursionists waiting for a train which was to start at midnight. When Michael left me I spent some time in an hotel, and then wandered down to the railway.

A wild crowd was on the platform, surging round the train in every stage of intoxication. It gave me a better instance than I had yet seen of the half-savage temperament of Connaught. The tension of human excitement seemed greater in this insignificant crowd than anything I have felt among enormous mobs in Rome or Paris.

There were a few people from the islands on the platform, and I got in along with them to a third-class carriage. One of the women of the party had her niece with her, a young girl from Connaught who was put beside me; at the other end of the carriage there were some old men who were talking Irish, and a young man who had been a sailor.

When the train started there were wild cheers and cries on the platform, and in the train itself the noise was intense; men and women shrieking and singing and beating their sticks on the partitions. At several stations there was a rush to the bar, so the excitement increased as we proceeded.

At Ballinasloe there were some soldiers on the platform looking for places. The sailor in our compartment had a dispute with one of them, and in an instant the door was flung open and the compartment was filled with reeling uniforms and sticks. Peace was made after a moment of uproar and the soldiers got out, but as they did so a pack of their women followers thrust their bare heads and arms into the doorway, cursing and blaspheming with extraordinary rage.

As the train moved away a moment later, these women set up a frantic lamentation. I looked out and caught a glimpse of the wildest heads and figures I have ever seen, shrieking and screaming and waving their naked arms in the light of the lanterns.

As the night went on girls began crying out in the carriage next us, and I could hear the words of obscene songs when the train stopped at a station.

In our own compartment the sailor would allow no one to sleep, and talked all night with sometimes a touch of wit or brutality and always with a beautiful fluency with wild temperament behind it.

The old men in the corner, dressed in black coats that had something of the antiquity of heirlooms, talked all night among themselves in Gaelic. The young girl beside me lost her shyness after a while, and let me point out the features of the country that were beginning to appear through the dawn as we drew nearer Dublin. She was delighted with the shadows of the trees--trees are rare in Connaught--and with the canal, which was beginning to reflect the morning light. Every time I showed her some new shadow she cried out with naïve excitement--

'Oh, it's lovely, but I can't see it.'

This presence at my side contrasted curiously with the brutality that shook the barrier behind us. The whole spirit of the west of Ireland, with its strange wildness and reserve, seemed moving in this single train to pay a last homage to the dead statesman of the east.

[やぶちゃん注:『「旦那、こいつあ、ばかに重いなあ。」彼は云つた。「此の中には金がはひつてるんだらう。」』原文は“'It's real heavy she is, your honour,' he said; 'I'm thinking it's gold there will be in it.'”。既に挿絵のキャプションで私の訳を示してあるが、『「旦那――この娘っこは、まあ、ばかに重いなぁ。」と彼は言った、「こん中は――金――と睨んだね。」』としたい。人称代名詞の誤用は既出。

「べダッド・イス・モール・アン・スルーアェ(ちえツ、そいつあ惜しかつた)。」原文は“'Bedad, is mor an truaghé' ('It's a big pity'),”。“bedad”は“begad”と同じで、“by God”の婉曲口語表現。やや罵りを含んで、「ちぇ」「とんでもない」「まぁ」。これは英語で、以下がゲール語になる。最後の単語の綴りに含まれる“truagh”は、ゲール語で“poor, wretched, sad, miserable, pitiful, woeful.”を表す形容詞である。ここは“miserable”が相応しいか。“is mor an”は自動翻訳機にかけると「素晴らしい」と訳される。「ちぇッ! そりゃ、素敵に惜しいね。」といった一種の逆説的誇張表現か。識者の御教授を乞う。なお、栩木氏はゲール語部分を音写して「シュ・モール・アン・トゥルア・エー」とされている。

「イニシマーン語の」原文は“Inishmaan pronounced”。「イニシマーンで発音される」、だからイニシマーン訛りのゲール語のことである。

『「フォルティエ」(いらつしやい)』原文“'Failte' (Welcome)”。ゲール語で「ようこそ」「いらっしゃい」の意。一般には“Cead Mile Failte”(ケード・ミル・フォルチャ)と言う。音写は「フォルチャ」「フォルチュ」「フォルーチャ」などと記される。

「人中で話しかけるのが恥かしかつたので、後をつけて來たのです。私を覺えていらつしやるかどうかみようと。」何故、マイケルは「人中で話しかけるのが恥かしかつた」のか? 勿論、マイケルの優しい人柄(相手にとって意外な場所で声をかけて吃驚させてはいけないという配慮)もあるが、直前のイニシマーン訛りの“Failte”から察するに、彼は自分の英語の発音に自信がないのかも知れない。少なくとも、公共の場で英語を話すのは気が引けたのではあるまいか? 更に、その後に「後をつけて」「私を覺えていらつしやるかどうかみようと」思ったというところからは、逆に人気のないところで遠慮せずに、シングにゲール語、それも確信犯のイニシマーン訛りのそれで声をかけて、それで私と分かるかどうかを試してみようという、茶目っ気もあるように思われる。

「パーネル記念祭」姉崎氏の注にある通り、アイルランド独立運動の政治指導者、アイルランド国民党党首チャールズ・スチュワート・パーネルの命日を以て彼の業績の記念とする日。アイルランド自治法の提案や、プロテスタントの地主による大地主制からカトリックの小作農の土地所有を認めさせる国土法を成立させた。女性スキャンダルによって惜しくも失脚したが、イギリスの首相ウィリアム・グラッドストンは自分が会った人物の中で最も非凡であったと述べている(以上はウィキの「チャールズ・スチュワート・パーネル」を参照した)。

「大暴民」原文は“enormous mobs”。桁外れの大群衆。「暴」はちょっときつ過ぎる。

「酒場へ驅け込む突貫があつたり」原文は“there was a rush to the bar”で、要は短い停車時間の間を惜しんで、バーに突進するように駆け込んでは数杯を煽ることを言っている。

「バリンスロー」“Ballinasloe”。音写は「バリナスロー」が正しい。ゲール語では“Béal Átha na Slua”(ベル・オーハ・ナ・スルア:「人込みの瀬の口」の意)古代よりこの町は人の集まる場所であった)。ゴールウェイ州の東端にある町。アイルランド中西部に位置する。古くはシャノン川の支流サック川の合流点として運河による水運の町として栄え、ダブリン―ゴールウェイ間の鉄道路線が町を通り、今も交通の要所である(以上はウィキの「バリナスロー」を参照した)。

「連れの女たちの一團が、非常な怒りに惡口を吐きながら、露はな頭や腕を戸口へさし入れた」以下の、この「女たち」の騒擾は、パーネル記念祭の宵祭のハレの雰囲気を語るのだが、しかしどうもそれだけではあるまい、という気もする。この女たちが憤激しているのは兵士たちと一緒に客車に載れなかったからと思われるが(兵士たちも乗れなかったようにはとれない。ホームで罵声を飛ばすのはあくまでこの「女たち」だけである)、定員をオーバーしてはいたのであろうが、譲り合えない程の超満員であったとも思われないのである。彼女は数人の兵士の、その「連れ」である。私は、この「女たち」が特別な職業の女(売春婦)であったことを匂わせてもいるような気がするのである(それは次のシーンの隣りのコンパートメントの女の嬌声――これは、この「女たち」の中で何人かの乗れた「女たち」の声ではないか――また、停車した駅で響いてくる「卑猥な歌」が、それを暗示させるように私には思えるのである。識者の御教授を乞う。

「だけど見えないわ。」という娘の台詞は、恐らく長身のシングが指差して教える早暁の彼方の景色を、「だけど私には、よく見えなくてよ。」と言っているのであろう。]

The Aran Islands

by J. M. Synge

Part Ⅱ

End

アラン島

ジョン・ミリングトン・シング著

姉崎正見訳

第二部

終

Críoch

第三部