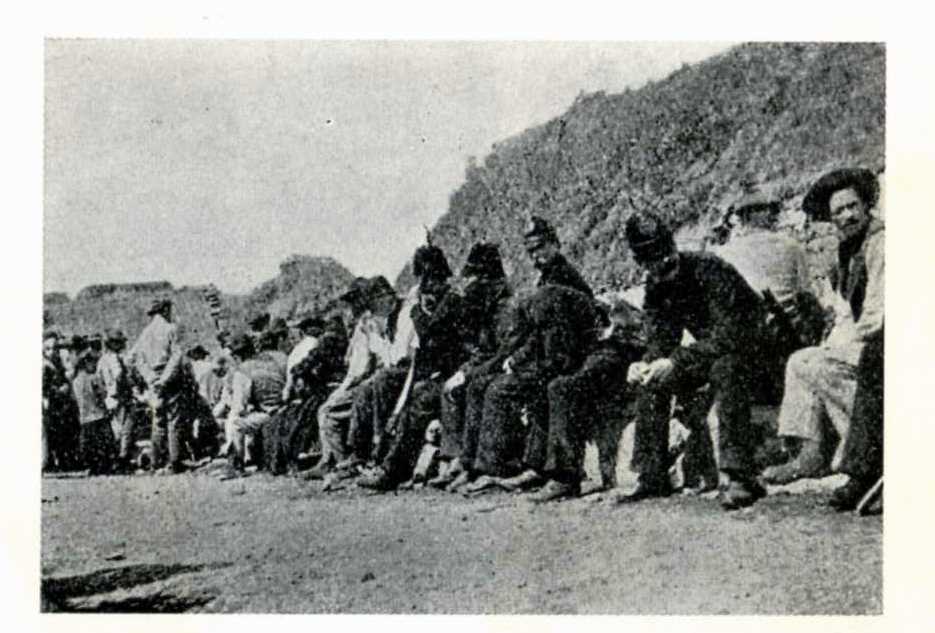

[島の男]

The Aran Islands

Part I

by J. M. Synge

With drawings by Jack B. Yeats

Dublin, Maunsel & Co., Ltd.

[1907]

アラン島

第一部

ジョン・ミリングトン・シング著

ウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツ挿絵

ダブリン マウンセル社刊

姉崎正見訳

附 やぶちゃん注

[島の男]

The Aran Islands

Part I

by J. M. Synge

With drawings by Jack B. Yeats

Dublin, Maunsel & Co., Ltd.

[1907]

アラン島

第一部

ジョン・ミリングトン・シング著

ウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツ挿絵

ダブリン マウンセル社刊

姉崎正見訳

附 やぶちゃん注

[やぶちゃん注:アイルランドの劇作家にして詩人であったジョン・ミリントン・シング (John Millington Synge 1871年~1909年)は、1898年から1902年にかけて4度、アイルランド島の西のゴールウェイ湾に浮かぶアラン諸島を訪れた。後に愛情に満ちた筆致でこの島に残るアイルランドの古形的民俗と人々の生活を活写したのが本作である(一冊に纏められた出版は1907年)。底本は一九三七年刊岩波文庫版を用いた。姉崎正見氏は東大附属図書館司書で昭和36(1961)年11月現職で逝去されている。従って著作権法五十一条により亡くなった翌年の1962年1月1日起算50年で、著作権保護期間は2010年1月1日までとなる。姉崎氏の没年については昨年年初に岩波書店に電話で直接確認をとってあるが、ネット上の記載でも確認が出来るので間違いない。冒頭に配された野上豊一郎の『「アラン島」について』も野上は昭和25(1950)年2月に逝去されているので、同じく著作権は消滅している。訳者によるポイント落ちの( )による割注は本文同ポイントで〔 〕示し、一部の踊り字は正字や「々」で示した。原則、底本の行空けのあるパートごとに(後半部には一部例外あり)訳文の後に原文を付し、更に私のオリジナルな注を附した。私は英語は苦手である。誤りや誤解があった場合は、御教授を乞う。底本の「口繪」に配されたシングがアラン島で撮った4枚の写真は底本のものを、原文及びイェイツの挿絵は“Intenet Sacred Text Archive”所収の“The Aran Islands by J. M. Synge”のものをそれぞれ用いた(冒頭の着色の一枚だけはイギリスの個人の方の蔵書から、同書の見開き扉絵の写真からを絵のみを切り取ったものである。万一、着色に著作権が生じている場合には削除する用意がある)。以上の写真と挿絵の配置は私の恣意によるもので(但し、写真については底本のキャプションにある『〇〇頁参照』という指示を勘案した)、挿絵の英語標題の訳は私が現代仮名遣・新字で附した。本頁は私のブログでの第一部の公開を経て、第一部全文を一括して作成したものである。――これを私と同じく母を失う聖痕(スティグマ)を受けた教え子に捧げる――【2011年3月10日

私の最愛の教え子の誕生日に】]

アラン島 シング作 姉崎正見譯

「アラン島」について

「アラン島」(The Aran Islands)はシングの戯曲を讀む人にとつて、興味ある貴重な文獻である。何となれば、イェーツも言つたやうに、シングの藝術の本質を形づくる永遠な高貴なものは、彼がアラン群島のそこここに寄寓して、土地の人たちから古い物語を聞き、それを目の前に見る現實の生活と比較することに依つて體得したものであり、讀者にその製作經過を感じさせないでは措かない素材がその中には豐富に盛られてあるから。

「アラン島」は、同時にまた、シングの戯曲を讀まない人にとつても、一つの興味多い讀物であることを失はない。何となれば、そこには世界の他のどこにも殆ど見られなくなつた傳統ある原始生活がまだ見られてあつたし、その生活の中にはひり込んで、同情と批判を以つて觀察した天才文人の忠實な記録でそれはあるから。

實際アランの岩島はシングに依つて生かされ、シングはまたアランを踏まへて彼の藝術を完成したのであつた。

シングにアランへ行けと忠告したのはイェーツであつた。それは一八九九年、シング二十八歳の時であつた。その七年前、シングはダブリン大學を出て、音樂者にならうと思つてドイツへ行き、作家に轉向しようと思つてフランスへ行き、フランスに三年ほどゐてイタリアヘ行き、捜すものを求め得ないでアイルランドに歸り、イェーツに逢ふ前年、一八九八年、アラン島に最初の訪問を試みて、またフランスへ行き、パリで先輩イェーツに逢ふと、イェーツはシングの天才を生かすにはラシーヌの幽靈を突き放して(當時シングはラシーヌに傾倒してゐたので)郷國の漁民の生活の中へ歸るのが一番だと感じ、それをシングに忠告したのであつた。シングはイェーツの忠告に従つてアランの生活を研究し、それを物にして遂にシェイクスピア以來の劇詩人と言はれるほどの製作をして、一九〇九年、三十八歳で孤獨の生涯を終つた。

シングは純眞で、内氣で、禁慾的で、さうして皮肉屋であつた。言語には殊に敏感で、近代詩の外にヘブライ語と固有アイルランド語をも知つてゐた。彼自身の書くものに彼自身獨自の表現を作り出すことにも成功した。それは彼の描いた性格の多くと共に、アランの漁民の生活觀察から得たものであつた。

私の若い友人姉崎正見君の飜譯が、さういつたシングの特長を生かさうとすることに周到な注意と努力の拂はれてあるのは推賞に値する。

昭和十二年二月 野上豊一郎

アラン島

緒 言

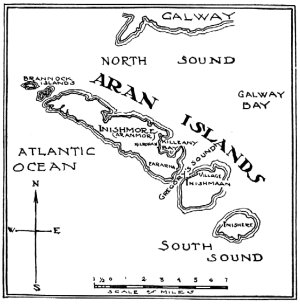

アラン島の地理は甚だ簡單であるが、これに就き一言する必要があらう。それは三つの島から成る。即ち、アランモア、北の島、長さ約九哩。次に、イニシマーン、中央の島、さしわたし約三哩半、形はほぼ圓形。さうして南の畠なるイニシール――愛蘭土語で東の島の意――は中央の島に似てゐるが、稍々小さい。それ等はゴルウェーから約三十哩離れ、その灣の中央に横はる。併し南方では、クレア郡の斷崖から、また北方では、コニマラの一角から程遠くはない。

アランモアの主要村キルロナンは繁華區域役所〔愛蘭土に於いて一八一九年移民に依つて起る借地問題を解決するために創設された役所〕に依つて發展した漁業のために大いに變革が行はれ、今では愛蘭土西岸の漁村と大した差違がなくなつてゐる。他の二島はそれより原始的であるが、其處にも變革は行はれつつある。併し本文中ではそれに就いて論及するほどの必要は感じられなかつた。

以下のページで、私は此の群島に於ける私の生活と、私の遭遇した事柄のありのままを述べ、何物をも創作せず、また本質的なものは何物をも變更しないで置いた。併し、私の語る人人に就いては、その名前を變へたり、引用した手紙を變へたり、また地理的・家族例の關係を變更したりして、成るべくその實體を現はさないやうにした。私は、全然彼等のためにならないやうな事は云はなかつたが、それでも斯く假裝を施したのは、彼等の厚意や友情を餘りに露骨に取扱つたといふ感じを

*

Author's Forword

The geography of the Aran Islands is very simple, yet it may need a word to itself. There are three islands: Aranmor, the north island, about nine miles long; Inishmaan, the middle island, about three miles and a half across, and nearly round in form; and the south island, Inishere--in Irish, east island,--like the middle island but slightly smaller. They lie about thirty miles from Galway, up the centre of the bay, but they are not far from the cliffs of County Clare, on the south, or the corner of Connemara on the north.

Kilronan, the principal village on Aranmor, has been so much changed by the fishing industry, developed there by the Congested Districts Board, that it has now very little to distinguish it from any fishing village on the west coast of Ireland. The other islands are more primitive, but even on them many changes are being made, that it was not worth while to deal with in the text.

In the pages that follow I have given a direct account of my life on the islands, and of what I met with among them, inventing nothing, and changing nothing that is essential. As far as possible, however, I have disguised the identity of the people I speak of, by making changes in their names, and in the letters I quote, and by altering some local and family relationships. I have had nothing to say about them that was not wholly in their favour, but I have made this disguise to keep them from ever feeling that a too direct use had been made of their kindness, and friendship, for which I am more grateful than it is easy to say.

[やぶちゃん注:「九哩」1mile は約1.6㎞。14.5㎞弱。

「繁華區域役所〔愛蘭土に於いて一八一九年移民に依つて起る借地問題を解決するために創設された役所〕」とあるが、この姉崎氏の割注の「一八一九年」は「一八九一年」の誤植であろう。原文“Congested

Districts Board”は正確には“Congested Districts Board for Ireland”で、これは時のソールズベリー内閣のスコットランド長官であった保守党政治家アーサー・バルフォア(1848年~1930年)の肝煎りで創設された一種の社会改良団体で、アイルランドの貧困層の特に婦人の雇用促進などを図ったもの(後に首相となるが、彼はアイルランド自治権拡大要求には反対であった)。ネット上では「アイルランド密集地区委員会」などと訳されている。貧困地域を対象としたシステムであるから「繁華」という訳語は違和感がある。]

第 一 部

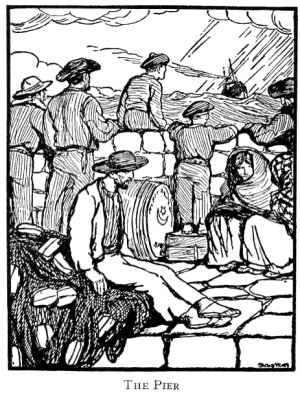

[桟橋]

私はアランモア〔アランの三島中最北に位する島〕にゐる。泥炭の火にあたり、部屋の下の小さな酒場から聞こえて來るゲール語の話し聲に耳傾けながら。

アランに來る汽船は潮時を見てやつて來る。私たちが深い霧に蔽はれたゴルウェーの波止場を見捨てたのは今朝六時であつた。

最初は右の方、波と霧の動く間に低い丘の連りが見えてゐたが、行くに從つてその影もなくなり、ただ索具にまつはる霧と小さな泡の渦卷のほか何も見えなくなつてしまつた。

乗客は少かつた。袋の中にゆるく小豚を縛りつけてやつて來た二人の男。首をすつぽりと襟卷に包んで船室に坐つてゐた三四人の少女。キルロナンの波止場を修繕に行く一人の大工、此の人は歩きまはつたり、私と話をしたりした。

三時間ばかりすると、アランが見え出した。先づ最初に荒涼たる岩が霧の中に海から盛り立つて現はれ、それから近づくに從つて、水上警察署や村が現はれて來た。

それから少し後、私は島の立派な道路に沿うて、両側の低い石垣越しに裸岩の僅かな平い畑地をのぞき込みながら歩いてゐた。私はこんな荒涼たる樣をかつて見たことがなかつた。灰色の水の溢れは、到る所で石灰岩の上を洗つて、時時道を激湍となしてゐた。それは、絶えず低い丘や岩の凹みの上をうねうねしたり、或ひは馬鈴薯畑や草原の間を通つて、隠れ場となつた隅の方へ失せ去つてゐた。雲が霽れる度ごとに、右手の下の方には海の端が見え、左手には高く島の裸かの隆起が見えた。たまに淋しい禮拜堂や學校の前を通つたり、また上に十字架がついて、祀つてある人の靈魂のために祈りをしてくれと銘を彫つてある石柱の列の前を通つたりもした。

人にはあまり逢はなかつた。ただ時時、キルロナンへ行く背の高い娘たちの群が通り過ぎて、樂しさうないぶかりの気持で私に呼びかけて、ゴルウェーの訛とはかなり違つた聞き馴れぬ抑揚の英語を話した。雨も寒さも物ともせず、彼女たちは元氣に笑ひ、ゲール語で大いにしやべりながら、私の傍を騒け過ぎて行き、濡れた岩の群を前より一層荒涼たらしめた。

正午少し過ぎて歸つて來る途中、一人の半盲の老人が私にゲール語で話しかけたが、大體からいつて、私はその方言の夥多と流暢に驚いた。

午後も雨が降り續いたので、私は此の宿にゐて、霧の中を數人の男がコニマラ〔愛蘭土本島、ゴルウェー州にある町〕から泥炭を積んで來た)

宿の婆さんが會話の教師を見付けてくれると約束してあつたが、少したつと、階段の上に足を引き摺る音がして、今朝話しかけた半盲の老人が部屋の中へ手探りではひつて來た。

彼を爐の所まで連れて行き、私たちは何時間も話した。彼はピートリもサー・ウィリアム・ワイルドも、その他現代の考古學者を知つてゐると云つた。それから、フィンク博士やペダーソン博士に愛蘭土語を教へた事もあれば、アメリカのカーティン氏に昔話を聞かした事もあると云つた。中年を少し過ぎて彼は崖から落ち、その時以來視力を失ひ、手や首が震へるやうになつたのであつた。

話してゐる時に、彼は火の上にのしかかり、震へながら目をつぶつてゐるが、顏は云ふに云はれぬやさしみがあつて、機智や惡意のこもつた話をする時は愉快の絶頂に達して輝き出し、宗教や妖精の事を話す時は暗く淋しくなつてしまつた。

彼は自分の力量と才能にも、自分の話す話が世界中のどの話よりもすぐれてゐることにも大きな自信を持つてゐた。話がカーティン氏の事になつた時、その人はアメリカでアランの物語を本にして、それを賣つて五百ポンド儲けたと云つた。

「それから、どうしたと思いますか?」彼は續けた。「私の話でうんと金を儲けた後、今度は自分で話を作つて本を書いた。そしてそれを出したのですが、半ペンスだつて儲かりませんや。どうです?」

その後、彼は一人の子供が妖精にとられた話をした。

或る日、近所の女が通つてゐた。道ばたで彼女が其奴を見た時、「まあ綺麗な子供」と云つた。

その子の母親が、「神さまお惠みください」と云はうとすると、聲が喉につかへて出なかつた。少したつてその子供の頸に傷のあるのに氣づいた。三日三晩、家の中が騒がしかつた。

「私は夜分シャツを着ないのです。」と彼は云つた。「でも家の騒ぎを聞くと、裸か同然で床から飛び起きて、

すると一人の啞がやつて棺に釘を打ちつける手眞似をした。

次の日は種芋に花が一杯咲いて、子供は母親にアメリカへ行くと云つた。

その晩子供は死んだ。「全くですよ、妖精に取られたのです。」と老人は云つた。

彼が歸つて行くと、小さい跣足の女の子が泥炭と火を起す

その女の子ははにかみやあつたが、話し好きで、立派な愛蘭土語が話せるとか、學校で愛蘭土語を教はつてゐるとか、此處では大人の女でも本土に足を踏み入れたことのない者が澤山あるのに、自分はゴルウェーに二度も行つたことがあるとか話した。

*

Part I

I AM IN Aranmor, sitting over a turf fire, listening to a murmur of Gaelic that is rising from a little public-house under my room.

The steamer which comes to Aran sails according to the tide, and it was six o'clock this morning when we left the quay of Galway in a dense shroud of mist.

A low line of shore was visible at first on the right between the movement of the waves and fog, but when we came further it was lost sight of, and nothing could be seen but the mist curling in the rigging, and a small circle of foam.

There were few passengers; a couple of men going out with young pigs tied loosely in sacking, three or four young girls who sat in the cabin with their heads completely twisted in their shawls, and a builder, on his way to repair the pier at Kilronan, who walked up and down and talked with me.

In about three hours Aran came in sight. A dreary rock appeared at first sloping up from the sea into the fog; then, as we drew nearer, a coast-guard station and the village.

A little later I was wandering out along the one good roadway of the island, looking over low walls on either side into small flat fields of naked rock. I have seen nothing so desolate. Grey floods of water were sweeping everywhere upon the limestone, making at limes a wild torrent of the road, which twined continually over low hills and cavities in the rock or passed between a few small fields of potatoes or grass hidden away in corners that had shelter. Whenever the cloud lifted I could see the edge of the sea below me on the right, and the naked ridge of the island above me on the other side. Occasionally I passed a lonely chapel or schoolhouse, or a line of stone pillars with crosses above them and inscriptions asking a prayer for the soul of the person they commemorated.

I met few people; but here and there a band of tall girls passed me on their way to Kilronan, and called out to me with humorous wonder, speaking English with a slight foreign intonation that differed a good deal from the brogue of Galway. The rain and cold seemed to have no influence on their vitality and as they hurried past me with eager laughter and great talking in Gaelic, they left the wet masses of rock more desolate than before.

A little after midday when I was coming back one old half-blind man spoke to me in Gaelic, but, in general, I was surprised at the abundance and fluency of the foreign tongue.

In the afternoon the rain continued, so I sat here in the inn looking out through the mist at a few men who were unlading hookers that had come in with turf from Connemara, and at the long-legged pigs that were playing in the surf. As the fishermen came in and out of the public-house underneath my room, I could hear through the broken panes that a number of them still used the Gaelic, though it seems to be falling out of use among the younger people of this village.

The old woman of the house had promised to get me a teacher of the language, and after a while I heard a shuffling on the stairs, and the old dark man I had spoken to in the morning groped his way into the room.

I brought him over to the fire, and we talked for many hours. He told me that he had known Petrie and Sir William Wilde, and many living antiquarians, and had taught Irish to Dr. Finck and Dr. Pedersen, and given stories to Mr. Curtin of America. A little after middle age he had fallen over a cliff, and since then he had had little eyesight, and a trembling of his hands and head.

As we talked he sat huddled together over the fire, shaking and blind, yet his face was indescribably pliant, lighting up with an ecstasy of humour when he told me anything that had a point of wit or malice, and growing sombre and desolate again when he spoke of religion or the fairies.

He had great confidence in his own powers and talent, and in the superiority of his stories over all other stories in the world. When we were speaking of Mr. Curtin, he told me that this gentleman had brought out a volume of his Aran stories in America, and made five hundred pounds by the sale of them.

'And what do you think he did then?' he continued; 'he wrote a book of his own stories after making that lot of money with mine. And he brought them out, and the divil a half-penny did he get for them. Would you believe that?'

Afterwards he told me how one of his children had been taken by the fairies.

One day a neighbor was passing, and she said, when she saw it on the road, 'That's a fine child.'

Its mother tried to say 'God bless it,' but something choked the words in her throat.

A while later they found a wound on its neck, and for three nights the house was filled with noises.

'I never wear a shirt at night,' he said, 'but I got up out of my bed, all naked as I was, when I heard the noises in the house, and lighted a light, but there was nothing in it.'

Then a dummy came and made signs of hammering nails in a coffin. The next day the seed potatoes were full of blood, and the child told his mother that he was going to America.

That night it died, and 'Believe me,' said the old man, 'the fairies were in it.'

When he went away, a little bare-footed girl was sent up with turf and the bellows to make a fire that would last for the evening.

She was shy, yet eager to talk, and told me that she had good spoken Irish, and was learning to read it in the school, and that she had been twice to Galway, though there are many grown women in the place who have never set a foot upon the mainland.

[やぶちゃん注:「夥多」は「かた」と読み、甚だ多いこと。

「脚長豚」原文“long-legged pigs”はそういう豚の品種ではないと思われる。所謂、子ブタや若い豚ではなく、親豚のことであろう。

「彼は一人の子供が妖精にとられた話をした。」ちょっとわかりにくいが、後のシャツの附言部分から、以下の、妖精に攫われた子供というのはこの話し手の老人の子であり、この「母親」とは彼の妻であることが分かる。]

雨が上つたので、私は島とその住民たちに眞實の初のお目見得をした。

私はキラニー――アランモアの最も貧しい村――を通り拔けて、南西へ海の中に伸びてゐる砂山の長い頸まで出かけた。其處で草の上に坐ると、コニマラの山には雲が霽れて、しばらくの間靑く起伏する前景は、遠くの山山を背景として、私にローマ近くの田舎を想ひ出させた。その時一艘の

尚行くと、一人の子供と男が隣村から下りて來て、私に話かけた。今度は英語が不完全ながら通用した。私が此の島には

彼等は私をつれて、此の島とイニシマーン――群島の中央の島――を隔ててゐる瀨戸まで行つて、二つの絶壁の間に大西洋から打ち寄せてゐるうねりを見せてくれた。

イニシマーンには愛蘭土語を習ひに來てゐる人が幾人か滯在してゐるさうで、男の子は島の中央に圓く藁の帶の樣に並んでゐる小屋の列を指した。その人たちはそこに住んでゐるのである。そこは殆んど人の住めさうな處とは思へなかつた。靑い物は何も見えず、人のゐるけはひといつては、その蜂の巣の樣な屋根とその上に空の際に屹立した一つの

やがてその道連れが行つてしまふと、ほかの二人の子供が私の直ぐ後からついて來た。たうとう私は振り向いて話をさせた。彼等は先づ自分たちの貧しい事を話し、それからその中の一人が云つた――

「あなたはホテルで一週間に十シリングも拂ふのでせう?」

「もつと。」 私は答へた。

「十二シリング?」

「もつと。」

「十五シリング?」

「まだ、もつと。」

それで彼等は引き下つて、それ以上聞かなかつた。私が彼等の好奇心を止める爲に嘘をついてゐると思つたのか、私の富に恐れてそれ以上續け得なかつたのか知らないが。

キラニーを再び通つてゐると、アメリカに二十年居たと云ふ男に出逢つた。彼はアメリカで健康を害して戻つて來たのだが、餘程以前に英語を忘れてしまつたと見えて、云ふ事が殆んどわからなかつた。見るからに希望もなく、不潔で、喘息氣味であつたが、二三百ヤードもー緒に歩いて行くと、立ち止つて銅貨をくれと云つた。私は持ち合はせてなかつたので煙草をやつた。すると彼は小屋の方へ歸つて居った。

彼が行つてしまふと、代りに二人の小さい娘の子がついて來たので、今度は彼等に話させた。

彼等は優しさのこもつた非常に微妙な異國的な抑揚で話し、夏になると、ladies and gentlemins(御婦人や旦那さんたち)を近所の名所へ案内して、バンプーティーズ〔まだ鞣さない牛皮で造つた一種のスリッパ或は草鞋〕や岩の中に澤山ある孔雀齒朶を賣りつける話を、歌のやうな調子で話した。

さてキルロナンに歸つて來て別れようとすると、二人の娘の子は自分達の履いてゐるバンプーティーズ即ち革草鞋の穴を見せて新しいのを買ふ代償を私にくれと云つた。私は財布が空だと云ふと、彼等は小聲で挨拶をして向うむいて波止場の方へ下りて行つた。

此の歸り道は非常にきれいだつた。愛蘭土にのみ、而かも雨後に限つて見られる烈しい島嶼的な明るさが、海にも空にもあらゆる漣波〔さざなみ〕を描き出し、入江の向うには山山のあらゆる皺襞〔ひだ〕を描き出してゐた。

*

The rain has cleared off, and I have had my first real introduction to the island and its people.

I went out through Killeany--the poorest village in Aranmor--to a long neck of sandhill that runs out into the sea towards the south-west. As I lay there on the grass the clouds lifted from the Connemara mountains and, for a moment, the green undulating foreground, backed in the distance by a mass of hills, reminded me of the country near Rome. Then the dun top-sail of a hooker swept above the edge of the sandhill and revealed the presence of the sea.

As I moved on a boy and a man came down from the next village to talk to me, and I found that here, at least, English was imperfectly understood. When I asked them if there were any trees in the island they held a hurried consultation in Gaelic, and then the man asked if 'tree' meant the same thing as 'bush,' for if so there were a few in sheltered hollows to the east.

They walked on with me to the sound which separates this island from Inishmaan--the middle island of the group--and showed me the roll from the Atlantic running up between two walls of cliff.

They told me that several men had stayed on Inishmaan to learn Irish, and the boy pointed out a line of hovels where they had lodged running like a belt of straw round the middle of the island. The place looked hardly fit for habitation. There was no green to be seen, and no sign of the people except these beehive-like roofs, and the outline of a Dun that stood out above them against the edge of the sky.

After a while my companions went away and two other boys came and walked at my heels, till I turned and made them talk to me. They spoke at first of their poverty, and then one of them said--'I dare say you do have to pay ten shillings a week in the hotel?' 'More,' I answered.

'Twelve?'

'More.'

'Fifteen?'

'More still.'

Then he drew back and did not question me any further, either thinking that I had lied to check his curiosity, or too awed by my riches to continue.

Repassing Killeany I was joined by a man who had spent twenty years in America, where he had lost his health and then returned, so long ago that he had forgotten English and could hardly make me understand him. He seemed hopeless, dirty and asthmatic, and after going with me for a few hundred yards he stopped and asked for coppers. I had none left, so I gave him a fill of tobacco, and he went back to his hovel.

When he was gone, two little girls took their place behind me and I drew them in turn into conversation.

They spoke with a delicate exotic intonation that was full of charm, and told me with a sort of chant how they guide 'ladies and gintlemins' in the summer to all that is worth seeing in their neighbourhood, and sell them pampooties and maidenhair ferns, which are common among the rocks.

We were now in Kilronan, and as we parted they showed me holes in their own pampooties, or cowskin sandals, and asked me the price of new ones. I told them that my purse was empty, and then with a few quaint words of blessing they turned away from me and went down to the pier.

All this walk back had been extraordinarily fine. The intense insular clearness one sees only in Ireland, and after rain, was throwing out every ripple in the sea and sky, and every crevice in the hills beyond the bay.

[やぶちゃん注:「イニシマーンには愛蘭土語を習ひに來てゐる人が幾人か滯在してゐるさうで、男の子は島の中央に圓く藁の帶の樣に並んでゐる小屋の列を指した。その人たちはそこに住んでゐるのである。」の部分は、そうした人々が現にそこに住んでいるとしか読めないのであるが、続く文章を読む限り、どうもそうではなく、嘗て滞在していた、というニュアンスを感じる。原文は“They

told me that several men had stayed on Inishmaan to learn Irish, and the

boy pointed out a line of hovels where they had lodged running like a belt

of straw round the middle of the island.”で“several men had stayed”“they

had lodged”と過去完了であるし、「その人たちはそこに住んでゐるのである。」に相当する独立文はない。訳者は後半部分であまりにも荒涼たる石積みの小屋で人は住めそうにない、人の気配はない、しかし、いるらしいと判断したものか。また、後文で彼らの訛が強烈で性人称なども区別しないとあるから、筆者はここも彼らの謂いの時制上のそうした特異性を出そうとしたものかも知れない。しかしやはり続く描写の人影もない荒涼感からは、ここは素直に例えば『イニシマーンにはアイルランド語を習いに来た人が幾人か滞在していたそうで、男の子は、その人たちが住んでいたという島の中央に円く藁の帯の樣に並んでいる小屋の列を指した。しかし、そこは殆んど人の住めそうな処とは思えなかった。……』とシンプルに続けて読みたくなるところである。

「孔雀齒朶」“maidenhair ferns”シダ植物門シダ目ホウライシダ科ホウライシダ属ホウライシダAdiantum capillus-veneris 若しくはクジャクシダAdiantum pedatum かその近縁種と思われる。一応、現在の“maidenhair ferns”は正式には前者の英名である(但し、植生域からはこれに同定するのはやや疑問か)。この属の種には現在でも観葉植物として高い価値を持つものが多い。]

今夜、一人の老人が私を訪ねて來た。彼は四十三年前、暫く此の島にゐた私の親戚を知つてゐると云つた。

「お前さんが船からやつて來る時、私は波止場の石垣の下で網を繕つてゐた。」と彼は云つた。「シングと云ふ名の人が、若し此の世界に出かけて來るとすれば、あの人こそ其の人だらうと、その時預言を云つた。」

彼は、少年時代を終らないうちに船員となつて、此の島を離れた時から此處に行はれた變遷を妙に短いが品位のある言葉で慨き續けた。

「私は歸つて來て、」と彼は云つた。「妹と一軒の家に住んだが、島は前とは全然變り、現在居る人から私は何のお蔭も蒙らないし、又彼等も私から何の

さういつた話からすると、此の男は一種獨特の

少したつて、茶の間の方へ下りて行くと二人の男がゐた。此の人たちは中の島〔イニシマーン〕から來て、此の島で日が暮れたのである。彼等は此處の人達より純撲で、恐らくより興味ある型の人であらう。念入りな英語で

*

This evening an old man came to see me, and said he had known a relative of mine who passed some time on this island forty-three years ago.

'I was standing under the pier-wall mending nets,' he said, 'when you came off the steamer, and I said to myself in that moment, if there is a man of the name of Synge left walking the world, it is that man yonder will be he.'

He went on to complain in curiously simple yet dignified language of the changes that have taken place here since he left the island to go to sea before the end of his childhood.

'I have come back,' he said, 'to live in a bit of a house with my sister. The island is not the same at all to what it was. It is little good I can get from the people who are in it now, and anything I have to give them they don't care to have.'

From what I hear this man seems to have shut himself up in a world of individual conceits and theories, and to live aloof at his trade of net-mending, regarded by the other islanders with respect and half-ironical sympathy.

A little later when I went down to the kitchen I found two men from Inishmaan who had been benighted on the island. They seemed a simpler and perhaps a more interesting type than the people here, and talked with careful English about the history of the Duns, and the Book of Ballymote, and the Book of Kells, and other ancient MSS., with the names of which they seemed familiar.

[やぶちゃん注:「シングと云ふ名の人が、若し此の世界に出かけて來るとすれば」原文は“if there is a man of the name

of Synge left walking the world”。この訳は「此の世界に出かけて來る」がやや奇異で、「此の世界」をアラン島と取るか、若しくは特殊な宗教観からある別な世界からこの現実世界へやって来るという意味になるが、それを伝えるには如何にも苦しい訳である。寧ろ、“walk

the world”は、“walk”の古語としての意を受けた、世を渡る、この世に生きるの謂いで、『もしシングという名の、今もこの世の中に生き残っている人がいるというなら』という意味であろう。

『「バリモートの書」「ケルスの書」』“Book of Ballymote, and the Book of Kells”はいずれもアイルランド文学の至宝。前者は14世紀の写本でケルトの神話を語るもので、アイルランドのスライゴ州バリモートに由来する。後者は紀元後700~800年にかけて制作された、四種の福音書によるイエス・キリストの生涯を華麗な文字で綴った初期キリスト教芸術の重宝で、ミーズ州ケルズに由来する。現在は「ケルズ」と表記するのが一般的。

「昔の寫本」原文“ancient MSS.”。“MSS.”は“manuscript”(マニュスクリプト)の省略形で手稿・写本のこと。]

到着した日に逢つた半盲の老人、即ち私の教師に心惹かれたにも關らず、私はイニシマーンに移る事にきめた。其處ではゲール語がもつと一般的に使はれ、その生活は、恐らく歐洲に殘つてゐる中で最も原始的な處である。

此の最後の日の一日中、私は半盲の案内人と、島の東部或ひは西北部に多くある古蹟を見物しながら過した。

出かける時、我我の道連れ――ムールティーン爺さんは時鳥と田雲雀の道連れの樣だと云つた――を笑つてゐる一團の娘の中に、際立つて精神的な表情をしてゐる美しい瓜實顏の女を私は見とめた。そんな顏は西部愛蘭土の女の或る型に著しいのである。此の日、後で老人は妖精とそれに騙された女の話を續けざまにしたが、島で信じられてゐる野蠻な神話と女の不思議な美しさの間に、関係がありさうに思へた。

正午ごろ一軒の廢屋の近くに休んでゐると、二人の綺麗な男の子が來て、傍に坐つた。ムールティーン爺さんは子供たちに、廢屋になつた譯、住んでゐた人の事を尋ねた。

「或る金持の百姓が前に建てた。」と彼等は云つた。「だが、二年の後に妖精の群に追ひ立てられてしまつた。」

子供たちは、今でも完全に殘つてゐる古い蜂の巣狀の家の一つを訪ねる爲に、北の方へかなりの道を我我について來た。我我は四つん這ひになつてはひり、内部の眞暗な中で立ち上つた時、ムールティーン爺さんは俗気臭いをかしな空想を考へ、若し彼が靑年であつて、若い女とはひつて來たら、どんな事になつたらうと語り出した。

それから彼は床下の眞ん中に坐つて、昔の愛蘭土の詩を誦し始めた。その音調の美しい純粋さは、意味はよく解らなかつたが、私に涕を催させた。

歸る途中、彼は妖精に就いてカトリック教的な話を聞かせてくれた。

悪魔が鏡で自分の姿を見た時、神と同じであると息つた。それで天主は彼とその家來の天使全部を天界から追ひ出した。天主が彼等を「つまみ出してゐる」最中、大天使が天主に彼等の或る者の赦しを願つた。それで墜落しつつあつた者は今でも空中に住んで、船を難破させたり、世の中に災害を起したりする力を持つてゐる。

それから話は神學の退屈な事柄に分れてゆき、かつて坊さんから聞いた愛蘭土語の説教や祈禱を長長と繰り返し初めた。

少し行くと、スレート葺の家へ來た。私は彼處に誰が住んでゐたのかと聞いた。

「學校の女の先生の樣な人」と彼は答へ、それからその年取つた顔を皺寄らせて、ちらりと異教的ないたづら氣を見せた。

「旦那、」と彼は云つた。「その中へはひつて、彼女に接吻したらよかつたらう。」

此の村から二哩ばかり行つた所で、カハル・オールウィン(美しき四人の人)と云ふ教會の廢墟と、その近くの盲目と癲癇によく效くので有名な靈泉を見物しに立寄つた。

我我がその泉の近くに腰掛けてゐると、道傍の家から一人の非常に年とつた老人が出て來て、泉の有名になつた譯を話した。

「スライゴの或る女が、生れながら盲目の息子を持つてゐた。或る晩、息子の目によく效く泉が、或る島の中にあると云ふ夢を見た。その朝、息子に話すと、或る老人が、彼女の夢にみたのはアランだと教へてくれた。

彼女は息子をゴルウェーの濱沿ひに連れて來て、カラハ〔アランで土人の乘る小船、木の骨組に麻布又は牛皮を張つて造る〕に乘つて出かけ、此の下に少し入江になつて見えるでせう。あすこに上陸した。

その女は當時私の父であつた家に歩いて來た。そして何を探してゐるかを話した。

私の父は、その夢と同じやうな處がある事を云つて、道案内に子供を遣ると云つた。

『少しも、それには及びません。其處はみんな夢で見て知つてゐるのですもの。』と彼女は云つた。

そこで子供と共に出かけ、その泉まで歩いて來て、跪いて祈りを初めた。それから水の方に手を差し伸べて、それを子供の目に當て、觸つたと思ふと、子供は『あッお母さん、美しい花を御覧!』と叫んだ。」

その後でムールティーンは密釀酒の酒盛りや若い時にした喧嘩のことをくはしく話した。それからサムソンに次いで力持であつたダーミッド〔愛蘭土の神話の勇者〕の話、及び島の東方にあるダーミッドとグレーン〔同じ神話の中の女王で、ダーミッドを誘惑したと傳へられる〕の寝床に就いての話となつた。ダーミッドはドルドイ僧に、火のついたシャツを着せられて、殺されたと云つた、――これは野天學校〔愛蘭土の臨時野外學校〕の先生の民謠の「學問」に依るのではないが、ダーミッドとヘルクレスの傳説とを結びつけ得る神話の斷片であらう。

それから我我はイニシマーンに就いて話した。

「あすこに、お前さんの話相手になる爺さんが居るだらう」と彼は云つた。「そして、妖精の話をする。だがあの人は此の十年間、二本の杖を賴りに歩いてゐる。若い時は四本足で、その後二本足で、それから年を取ると三本足で歩く者を知つてゐるかね?」

私は答を與へた。

「おお、旦那、」彼は云つた。「お前さんは利巧だ。神の惠みよ、お前さんの上に。さうだ、私は今三本足、あすこの爺さんは四本足に戻つた。でもどつちの

*

ln spite of the charm of my teacher, the old blind man I met the day of my arrival, I have decided to move on to Inishmaan, where Gaelic is more generally used, and the life is perhaps the most primitive that is left in Europe.

I spent all this last day with my blind guide, looking at the antiquities that abound in the west or north-west of the island.

As we set out I noticed among the groups of girls who smiled at our fellowship--old Mourteen says we are like the cuckoo with its pipit--a beautiful oval face with the singularly spiritual expression that is so marked in one type of the West Ireland women. Later in the day, as the old man talked continually of the fairies and the women they have taken, it seemed that there was a possible link between the wild mythology that is accepted on the islands and the strange beauty of the women.

At midday we rested near the ruins of a house, and two beautiful boys came up and sat near us. Old Mourteen asked them why the house was in ruins, and who had lived in it.

'A rich farmer built it a while since,' they said, 'but after two years he was driven away by the fairy host.'

The boys came on with us some distance to the north to visit one of the ancient beehive dwellings that is still in perfect preservation. When we crawled in on our hands and knees, and stood up in the gloom of the interior, old Mourteen took a freak of earthly humour and began telling what he would have done if he could have come in there when he was a young man and a young girl along with him.

Then he sat down in the middle of the floor and began to recite old Irish poetry, with an exquisite purity of intonation that brought tears to my eyes though I understood but little of the meaning.

On our way home he gave me the Catholic theory of the fairies.

When Lucifer saw himself in the glass he thought himself equal with God. Then the Lord threw him out of Heaven, and all the angels that belonged to him. While He was 'chucking them out,' an archangel asked Him to spare some of them, and those that were falling are in the air still, and have power to wreck ships, and to work evil in the world.

From this he wandered off into tedious matters of theology, and repeated many long prayers and sermons in Irish that he had heard from the priests.

A little further on we came to a slated house, and I asked him who was living in it.

'A kind of a schoolmistress,' he said; then his old face puckered with a gleam of pagan malice.

'Ah, master,' he said, 'wouldn't it be fine to be in there, and to be kissing her?'

A couple of miles from this village we turned aside to look at an old ruined church of the Ceathair Aluinn (The Four Beautiful Persons), and a holy well near it that is famous for cures of blindness and epilepsy.

As we sat near the well a very old man came up from a cottage near the road, and told me how it had become famous.

'A woman of Sligo had a son who was born blind, and one night she dreamed that she saw an island with a blessed well in it that could cure her son. She told her dream in the morning, and an old man said it was of Aran she was after dreaming.

'She brought her son down by the coast of Galway, and came out in a curagh,

and landed below where you see a bit of a cove.

'She walked up then to the house of my father--God rest his soul--and she told them what she was looking for.

'My father said that there was a well like what she had dreamed of, and that he would send a boy along with her to show her the way.

"There's no need, at all," said she; "haven't I seen it all in my dream?"

'Then she went out with the child and walked up to this well, and she kneeled down and began saying her prayers. Then she put her hand out for the water, and put it on his eyes, and the moment it touched him he called out: "O mother, look at the pretty flowers!"

After that Mourteen described the feats of poteen drinking and fighting that he did in his youth, and went on to talk of Diarmid, who was the strongest man after Samson, and of one of the beds of Diarmid and Grainne, which is on the east of the island. He says that Diarmid was killed by the druids, who put a burning shirt on him,--a fragment of mythology that may connect Diarmid with the legend of Hercules, if it is not due to the 'learning' in some hedge-school master's ballad.

Then we talked about Inishmaan.

'You'll have an old man to talk with you over there,' he said, 'and tell you stories of the fairies, but he's walking about with two sticks under him this ten year. Did ever you hear what it is goes on four legs when it is young, and on two legs after that, and on three legs when it does be old?'

I gave him the answer.

'Ah, master,' he said, 'you're a cute one, and the blessing of God be on you. Well, I'm on three legs this minute, but the old man beyond is back on four; I don't know if I'm better than the way he is; he's got his sight and I'm only an old dark man.'

[やぶちゃん注:「田雲雀」は「たひばり」と読む。原文“pipit”。スズメ目セキレイ科タヒバリAnthus pinoletta のこと。正式な英名は“Water Pipit”で、彼らはカッコウ目カッコウ科カッコウ属ホトトギスCuculus poliocephalus の托卵相手である(カッコウ目カッコウ科とホトトギス目ホトトギス科は同じである)。

「野蠻な神話」原文“wild mythology”。『粗野な神話』、『

「ムールティーン爺さんは俗気臭いをかしな空想を考へ」原文“old Mourteen took a freak of earthly humour”で、訳文はやや生硬な印象を受ける。『ムールティーン老師は若い頃のちょっとしたいたずらっ気を発揮して』ぐらいの感じであろう。

「坊さん」“priests”。カトリック教会の司祭たち。

「學校の女の先生の樣な人」“'A kind of a schoolmistress,'”『まあ、言うたら、

「カハル・オールウィン(美しき四人の人)」原文の“Ceathair Aluinn”はゲール語で“Ceathair”は4、“Aluinn”は美しい、の意。但し“Ceathair”はネット上のネイティヴの発音では「カハル」ではなく「エタフェル」と言うように聴こえる。

「カラハ」原文の綴りは“curagh”であるが、現在では一般には“currach”で、ゲール語では“koroko”、しばしば英国風には“curragh”と綴る。但し、スペルでは二つの“r”を一つで済ませるスペルも用いられるらしいので、シングの綴りは誤りではないものと思われる。

以下の盲人を開明させる聖なる泉の話は、後にシングが発表する戯曲「聖者の泉」を髣髴とさせる(リンク先は私の片山廣子(松村みね子)訳「聖者の泉」)。そういえば、あの主人公の男の名は“Martin”――マーチン、この老人の名は“Mourteen”、ムールティーン=マーチーンである。

「その女は當時私の父であつた家に歩いて來た。」ちょっと妙な日本語だなと思って原文を見ると、“She walked up then to the house of my father--God rest his soul--”となっており、これは敬虔なカトリック教徒の習慣が出た直接話法をそのままに写したことが分かった。則ち、死者のことを口にする時のマナーとして、「その亡き人の魂に神の御恵みを!」と添えたのである。だからここは『彼女が私のその頃の父――おぉ、安らかにねむり給え!――の家へとやって来て』といった台詞となる。

「密釀酒」原文は“poteen”で、ゲール語で非合法に蒸留したアイリッシュ・ウイスキーのこと。ポーティン。

「ドルドイ僧」は「ドルイド僧」の錯字。“the druids”は古代ケルト人のドルイド教の神官。聖樹信仰を核に、霊魂不滅・輪廻を中心教義とし、占星術を始めとする各種の占術を駆使した。

『――これは野天學校〔愛蘭土の臨時野外學校〕の先生の民謠の「學問」に依るのではないが、ダーミッドとヘルクレスの傳説とを結びつけ得る神話の断片であらう。』もやや分かり難い。原文は“--a fragment of mythology that may connect Diarmid with the legend of Hercules, if it is not due to the 'learning' in some hedge-school master's ballad.”であるが、訳の後半は問題がない。問題は“if it is not due to the 'learning' in some hedge-school master's ballad.”の部分である。まず、“hedge-school master”『アイルランドの臨時野外学校の先生』である。このヘッジ・スクールというのは、十八世紀初頭から十九世紀前半にかけて、アイルランド全土に広がった非合法の民衆教育組織で、垣根の陰に隠れて教師と子らが集って学校活動が行われたことに由来し、教区聖職者を中心に代書業・測量師等などを副業とした多彩な教師が運営し、そうした貧しい子らの親が授業料を支払って運営されていた独特の民間教育機関である。ペイ・スクールとも言う。このヘッジ・スクールがアイルランドの教育向上に大いに貢献したことは言うまでもない。但し、いわばそうした非公認の「先生」の中には、「先生」とは言うものの大した学識もない、“'learning'”、カッコ書きの 『(にわかハッタリの)学問』の持ち主もいたであろう(今の教師にも私を含めてゴマンといる)。そうした『にわか学問』によってデッチ上げられた“ballad”、バラッド、『民間伝承の物語詩』に“if it is not due to”『基づくものでないないとすれば』という意味であろう。則ち、ここは『――これはダーミッドとヘルクレス伝説とを結びつけ得る神話の断片であろう――但し、これがどこぞのヘッジ・スクールの大先生の「にわか学問」が発祥のバラードによるものでなかったとすれば、の話である。』というピリッと皮肉を込めた附言なのである。]

私は遂にイニシマーンの小さな家に落着いた。私の部屋の方へ開いてゐる茶の間から、絶えずゲール語の單調な聲がはひつて來る。

今朝早く、此の家の男が四挺櫂のカラハ――即ち、四人の漕手が居て、銘銘が二本づつ使へるやうに両側に四つの櫂があるカラハ――で私を迎へに來た。そして正午少し前出立した。

人間が初めて海に乘り出して以來、原始人に使はれた型の粗末な布のカヌーに乘つて、文明から逃れ出てゐると思ふと、私には云ひ知れぬ滿足の一時であつた。

我我は、常に碇泊してゐる

再び出發した時は、小さな帆を船首に揚げて、瀨戸横斷の途に就いた。その跳ぶやうな動搖はボートの重い進行とは餘程違つてゐた。

帆はただ補助として用ひるに過ぎず、帆を揚げた後も男たちは漕ぎ續ける。そして漕手は四つの横渡しの腰掛を占めてゐるので、私は船尾のカンバスの上、掩はれた木の骨組の

出かけた時、四月の朝は晴れ渡つて蒼いキラキラする波がカヌーをその中で押しやつてくれるやうであつたが、島に近づくにつれて、行手の岩の後から雷雨が起つて靜かな大西洋の氣分を一時かき交ぜた。

我我は小さな波止場から上陸した。其處から、アランモアに於けると同じやうに、粗末な路が小さな畑と一面の裸岩の間をねけて、村まで續いてゐる。船頭の中で最も年下の息子の十七歳ぐらゐの男の子は私の教師となり、また道案内人となる筈であるが、此男の子が波止場で私を待つてゐて、家まで案内してくれた。一方、男たちはカラハを片付け、私の荷物を提げてゆるゆる後から附いて來た。

私の部屋は家の一端にあつて、板張の床下と天井、互ひに向き合つた二つの窓がある。また茶の間には土間とむき出しの棰木があり、向き合つて二つの戸が戸外へ開くやうについてゐるが、窓はない。その奥に茶の間の半分ほどの廣さの二つの小さな部屋があるが、こ心れには一つづつの窓がある。

私は大抵の時を茶の間で過す積りだが、其處だけでも多くの美しさがあり、特色がある。爐の周りの椅子に腰掛けて集まる女たちの赤い着物は東洋的な豐かな色彩を出し、また泥炭の煙で軟かい茶褐色に彩られた壁は床下の灰色の土と色のよい配合を作る。いろいろの釣道具、網、男の雨合羽などが壁やむき出しの棰木に懸り、頭の上、草葺の屋根の下には革草鞋を造る剥いだままの年の皮がある。

此の群島のあらゆる品物には殆んど個性的な特色がある。その特色は藝術を全然知らない簡素な生活に、中世生活の藝術的美しさのやうな物を加へる。カラハ、

着物の質素と一樣さは又他の方面で、郷土色に美しさを加へる。女は赤いペティコート〔婦人或は子供の着る上着、普通腰の邊より下袴が下がる。〕や茜で染めた島の羊毛のジャケツを着て、その上に普通格子縞の襟卷を胸に卷いて、背中で結ぶ。雨の日には、顔の周りに腰帶をして、もう一つのペティコートを頭からかぶる。若ければ、ゴルウェーで着るやうな重い襟卷を使ふ。時には他の纏物をする。私が夕立の最中到着した時、數人の女が男の胴着を體の周りにボタンで締めて着てゐるのを見た。裾は餘り膝の下まで届かず、皆用意して持つてゐる濃い紺色の靴下を履いて、逞しい足を見せてゐる。

男は三つの色物を着る、即ち無地の羊毛、紺色の羊毛、無地と紺色の羊毛を互ひ違ひに織り交ぜた灰色のフランネルである。アランモアでは、多くの若い男は普通の漁夫の着るジャージー・ジャケツを用ひるが、此の島ではただ二人だけしか見かけなかつた。

フランネルは安いので――女たちが家の羊の毛から絲を造り、それをキルロナンで一ヤード四ペンスで織子が織るので――、男達は何枚も胴着を着、羊毛のズボンを重ねて穿くらしい。大抵の者は私の着物の輕いのに驚く。波止場で一寸口をきいた老人は私が岸に來ると「私の少しの着物」で寒くはなからうかと尋ねた。

茶の間で着物から水しぶきを乾かしてゐると、私の歩いて來るのを見た數人の人たちは、大抵敷居の所で、「今日は、ようこそ」と云ふやうな挨拶の言葉を、小聲で云ひながら、私と話さうとはひつて來た。

此の家のお婆さんの丁寧なのは非常に人の心を惹く、彼女の云ふ事は――英語を話さないので――大部分解らなかつたが、如何にもしとやかに客を年齡に應じて、或ひは椅子へ或ひは床机へと案内して、英語の會話につり込ませるまで二言三言を言つてゐるのだと見られた。

暫く私の來たことが興味の中心になつて、はひつて來る人たちはしきりに私と話したがる。

或る者は普通の百姓よりずづと正確にその考へを發表し、また或る者は絶えずゲール語の訛を出して、現代の愛蘭土語には中性名詞がないので、it の代りに

she か或は he を使ふ。

中には不思議にも単語を多く知つてゐる者もあるが、また英語の極く普通の言葉だけしか知らず、意味を表はすのに勢ひ巧妙な工夫をしなければならない者もある。我我の話し得る話題の中では戰爭を好むらしく、アメリカとスペインの戰爭は非常な興味を起させた。どの家族にも大西洋を渡らねばならなかつた者を親戚に持ち、また合衆國から來る小麥と燒豚を食べてゐるので、若しアメリカに何か起つたら暮らせなくなるだらうと云ふ漠然たる恐怖を持つてゐた。

外國語も亦好む話題であつて、二國語を使ふ彼等は、いろいろ違つた言葉で表現したり考へたりするのは如何なる意義があるかに就いて正しい考へを持つてゐる。此の島で知る外国人の多くは言語學者であるから、彼等は言語の研究、殊にゲール語の研究が外の世界でやつてゐる重な仕事であると勢ひ思ひ込んでゐる。

「私はフランス人にも、デンマーク人にも、ドイツ人にも逢つたことがある。」と一人の男が云つた。「その人たちは愛蘭土語の本をどつさり持つてゐて、我我よりもよく讀む。此の頃、世界で、金持でゲール語を研究してない人はないですよ。」

或る時は、簡單な文章の佛語を私に要求する。暫くその音調を聞いてゐると、大概の者は見事な正確さで眞似する事が出來た。

*

I am settled at last on Inishmaan in a small cottage with a continual drone of Gaelic coming from the kitchen that opens into my room.

Early this morning the man of the house came over for me with a four-oared curagh--that is, a curagh with four rowers and four oars on either side, as each man uses two--and we set off a little before noon.

It gave me a moment of exquisite satisfaction to find myself moving away from civilisation in this rude canvas canoe of a model that has served primitive races since men first went to sea.

We had to stop for a moment at a hulk that is anchored in the bay, to make some arrangement for the fish-curing of the middle island, and my crew called out as soon as we were within earshot that they had a man with them who had been in France a month from this day.

When we started again, a small sail was run up in the bow, and we set off across the sound with a leaping oscillation that had no resemblance to the heavy movement of a boat.

The sail is only used as an aid, so the men continued to row after it had gone up, and as they occupied the four cross-seats I lay on the canvas at the stern and the frame of slender laths, which bent and quivered as the waves passed under them.

When we set off it was a brilliant morning of April, and the green, glittering waves seemed to toss the canoe among themselves, yet as we drew nearer this island a sudden thunderstorm broke out behind the rocks we were approaching, and lent a momentary tumult to this still vein of the Atlantic.

We landed at a small pier, from which a rude track leads up to the village between small fields and bare sheets of rock like those in Aranmor. The youngest son of my boatman, a boy of about seventeen, who is to be my teacher and guide, was waiting for me at the pier and guided me to his house, while the men settled the curagh and followed slowly with my baggage.

My room is at one end of the cottage, with a boarded floor and ceiling, and two windows opposite each other. Then there is the kitchen with earth floor and open rafters, and two doors opposite each other opening into the open air, but no windows. Beyond it there are two small rooms of half the width of the kitchen with one window apiece.

The kitchen itself, where I will spend most of my time, is full of beauty and distinction. The red dresses of the women who cluster round the fire on their stools give a glow of almost Eastern richness, and the walls have been toned by the turf-smoke to a soft brown that blends with the grey earth-colour of the floor. Many sorts of fishing-tackle, and the nets and oil-skins of the men, are hung upon the walls or among the open rafters; and right overhead, under the thatch, there is a whole cowskin from which they make pampooties.

Every article on these islands has an almost personal character, which gives this simple life, where all art is unknown, something of the artistic beauty of medieval life. The curaghs and spinning-wheels, the tiny wooden barrels that are still much used in the place of earthenware, the home-made cradles, churns, and baskets, are all full of individuality, and being made from materials that are common here, yet to some extent peculiar to the island, they seem to exist as a natural link between the people and the world that is about them.

The simplicity and unity of the dress increases in another way the local air of beauty. The women wear red petticoats and jackets of the island wool stained with madder, to which they usually add a plaid shawl twisted round their chests and tied at their back. When it rains they throw another petticoat over their heads with the waistband round their faces, or, if they are young, they use a heavy shawl like those worn in Galway. Occasionally other wraps are worn, and during the thunderstorm I arrived in I saw several girls with men's waistcoats buttoned round their bodies. Their skirts do not come much below the knee, and show their powerful legs in the heavy indigo stockings with which they are all provided.

The men wear three colours: the natural wool, indigo, and a grey flannel that is woven of alternate threads of indigo and the natural wool. In Aranmor many of the younger men have adopted the usual fisherman's jersey, but I have only seen one on this island.

As flannel is cheap--the women spin the yarn from the wool of their own sheep, and it is then woven by a weaver in Kilronan for fourpence a yard--the men seem to wear an indefinite number of waistcoats and woollen drawers one over the other. They are usually surprised at the lightness of my own dress, and one old man I spoke to for a minute on the pier, when I came ashore, asked me if I was not cold with 'my little clothes.'

As I sat in the kitchen to dry the spray from my coat, several men who had seen me walking up came in to me to talk to me, usually murmuring on the threshold, 'The blessing of God on this place,' or some similar words.

The courtesy of the old woman of the house is singularly attractive, and though I could not understand much of what she said--she has no English--I could see with how much grace she motioned each visitor to a chair, or stool, according to his age, and said a few words to him till he drifted into our English conversation.

For the moment my own arrival is the chief subject of interest, and the men who come in are eager to talk to me.

Some of them express themselves more correctly than the ordinary peasant, others use the Gaelic idioms continually and substitute 'he' or 'she' for 'it,' as the neuter pronoun is not found in modern Irish.

A few of the men have a curiously full vocabulary, others know only the commonest words in English, and are driven to ingenious devices to express their meaning. Of all the subjects we can talk of war seems their favourite, and the conflict between America and Spain is causing a great deal of excitement. Nearly all the families have relations who have had to cross the Atlantic, and all eat of the flour and bacon that is brought from the United States, so they have a vague fear that 'if anything happened to America,' their own island would cease to be habitable.

Foreign languages are another favourite topic, and as these men are bilingual they have a fair notion of what it means to speak and think in many different idioms. Most of the strangers they see on the islands are philological students, and the people have been led to conclude that linguistic studies, particularly Gaelic studies, are the chief occupation of the outside world.

'I have seen Frenchmen, and Danes, and Germans,' said one man, 'and there does be a power a Irish books along with them, and they reading them better than ourselves. Believe me there are few rich men now in the world who are not studying the Gaelic.'

They sometimes ask me the French for simple phrases, and when they have listened to the intonation for a moment, most of them are able to reproduce it with admirable precision.

[やぶちゃん注:「掩はれた木の骨組の

「棰木」は「たるき」と読む。垂木。

「英語の會話につり込ませるまで二言三言を言つてゐるのだと見られた。」この訳文は文字通り“drift”(意味)が分からない。原文を見ると、“and said a few words to him till he drifted into our English conversation.”で、この“him”は直前の“visitor”を指し、『私を訪ねてきた幾分かは英語を喋れる男たちが私との英語の会話に入る前、その彼らにこのお婆さんが、二言三言、ゲール語で声をかけているその雰囲気を見る限り、彼女が丁寧で非常に人の心を惹くものを持った女性であることが感じられる』ということであろう。ここではシング自身も、このお婆さんの訛の強いゲール語は分からないのであって、いわばその雰囲気からお婆さんの人柄を体感しているということではなかろうか。

「アメリカとスペインの戰爭」一八九八年四月に勃発した米西戦争のこと。シングが最初にアラン島を訪問したのは同年五月十日から六月二十五日までであったから、文字通り、アップ・トゥ・デイトな関心事であった。結果的には八月にスペインの敗北で終結し、カリブ海及び太平洋のスペイン旧植民地の管理権はアメリカへ移った。

「燒豚」原文は“bacon”であるから今の感覚では違和感がある。ベーコンは塩漬けの豚肉を燻製にしたものであり、焼豚は豚肉を炙り焼きや煮込んだもので製法も異なる。本書が刊行された昭和十二(一九三七)年ではベーコンは一般的な日本語としては通じ難かったということか。]

今朝、愛蘭土語を私に教へてゐる靑年のマイケルと島を散歩しようと出かけた時、宿の方へ向つて行く一人の老人に出逢つた。彼は本土から來たと見えるみすぼらしい黑い着物を着て、遠くから見れば人間よりは一層蜘蛛に見えるほどにリューマチスのため體が曲つてゐた。

マイケルはあれはあちらの島でムールティーン爺さんが話した物語師のパット・ディレイン爺さんであると語つた。その人は偶然にも私を訪ねて來るらしいので、引返したかつたが、マイケルは聞かなかつた。

「我我が歸つたら火の側に居るでせう」と彼は云つた。「心配はありませんよ。これから少しづつ話す時は充分あるでせう。」

彼の云つた通りであつた。それから何時聞かの後、私が茶の間の方へ下りて行つた時、パット爺さんは炭の爐で目をしばたたかせながら、爐の側にまだ居た。

彼は非常に器用にまた流暢に英語を話す。これは彼が若い時、收穫の爲英國の田舍に數ケ月働きに行つてゐた爲に違ひない。

二三の型の如き挨拶の後、彼はオールド・ヒン(即ち、インフルエンザ)にやられて

お婆さんが私の食事を作つてゐる間、彼は私に物語が好きかどうかを尋ねて、若しゲール語に附いて行けるならよいがと云ひ足しながら、英語で一つの物語をしようと云つた。そして語り始めた。――

*

When I was going out this morning to walk round the island with Michael, the boy who is teaching me Irish, I met an old man making his way down to the cottage. He was dressed in miserable black clothes which seemed to have come from the mainland, and was so bent with rheumatism that, at a little distance, he looked more like a spider than a human being.

Michael told me it was Pat Dirane, the story-teller old Mourteen had spoken of on the other island. I wished to turn back, as he appeared to be on his way to visit me, but Michael would not hear of it.

'He will be sitting by the fire when we come in,' he said; 'let you not be afraid, there will be time enough to be talking to him by and by.'

He was right. As I came down into the kitchen some hours later old Pat was still in the chimney-corner, blinking with the turf smoke.

He spoke English with remarkable aptness and fluency, due, I believe, to the months he spent in the English provinces working at the harvest when he was a young man.

After a few formal compliments he told me how he had been crippled by an attack of the 'old hin' (i.e. the influenza), and had been complaining ever since in addition to his rheumatism.

While the old woman was cooking my dinner he asked me if I liked stories, and offered to tell one in English, though he added, it would be much better if I could follow the Gaelic. Then he began:--

[やぶちゃん注:「それから何時聞かの後、私が茶の間の方へ下りて行つた時、パット爺さんは炭の爐で目をしばたたかせながら、爐の側にまだ居た。」は若干気になる。原文は“As

I came down into the kitchen some hours later old Pat was still in the

chimney-corner, blinking with the turf smoke.”で、“came down”とある。ところが既に読者には分かっている通り、彼の宿は平屋である。これは冒頭前文の“I

met an old man making his way down to the cottage.”を受けるものであろう。則ち、シングとマイケルは島巡りをするために、宿からある小道を伝って登って行った。そのルートとは異なった宿へ下る小道をパット爺さんは降りてきたのであった。シングが「数時間の後」の島巡りを終えて、「下り道を降りて」、宿の、その茶の間へと入った時、パット爺さんは「炭の爐で目をしばたたかせながら、爐の側にまだ居た」ということであろう。この間合いが、アランの神話へと導かれる前哨として美事、と私は思うのである。

「オールド・ヒン(即ち、インフルエンザ)」原文“'old hin' (i.e. the influenza)”。“hin”が分からない。栩木伸明氏訳2005年みすず書房刊の「アラン島」では、『めんどりバーバ』(ルビに『インフルエンザ』)という不思議な訳がなされていた。それを凝っと見ながら――成程!――と合点した。“hin”は“hen”(雌鶏)のパット爺さんの訛なのだ。栩木氏の「バーバ」は「雌鶏の御婆ちゃん」の意ではあるまいか?――それにしても、どうしてインフルエンザをこう呼ぶのだろう。まさか、鳥インフルエンザじゃあなかろうし、くしゃみの声とか、くしゃみをしたときの動作からの老いた雌鶏の連想だろうか?]

クレア郡に二人の百姓がゐた。一人は息子を持ち、もう一人の立派な金持の方は一人の娘を持つてゐた。

若者はその娘を妻に貰ひたかつた。父は彼にあのやうな女を貰ふには金が澤山要るだらうが、よいと思ふならやつてみよと云つた。

「やつてみませう」と若者は云つた。

彼は金のありつたけを袋につめた。さうしてもう一人の百姓の所へ行つて、その前に金を投げ出した。

「たつたそれだけか?」と娘の父は云つた。

「これだけです。」 オーコナーは云つた。(若者の名はオーコナーであつた。)

「それではとても娘と釣り合はない。」 父親が云つた。

「試してみませう。」 オーコナーは云つた。

そこで、片方には娘を、もう片方には金を、秤の上に載せて量つた。娘の方がどつかりと地面に落ちたので、オーコナーは袋をとつて往來へ出た。

歩いて行くと、一人の小男が居て、壁にもたれて立つてゐる所へ來た。

「袋を持つて何處へ行く?」小男が云つた。

「家へ行くのです。」 オーコナーが云つた。

「金が要るのぢやないか」小男が云つた。

「その通りです。」 オーコナーが云つた。

「要るだけお前に遣らう。」小男は云つた。「かう云ふ約束をしよう。一二年たつたら遣つた金を返してくれ。返さなかつたら、お前の肉を五ポンド切り取つて貰ふぞ。」

二人の間にそんな約束が出來た。その男はオーコナーに金の袋を與へ、彼はそれを持ち歸つて娘と結婚した。

彼等は金持になり、クレアの絶壁に妻の爲に大きな屋敷を建て、荒海を直ぐ眺められる窓を付けた。

或る日、彼は妻と登つて行き、荒海を眺めてゐると、一艘の船が岩に乘り上げ、帆もかけてないのを見た。それは岩の上で難破してゐたので、茶と立派な絹が積み込んであつた。

オーコナーとその妻は難破船を見に下りて行き、夫人は絹を見ると、それで着物が作りたいと云つた。

彼等は水夫たちから絹を買つた。船長がその代金を貰ひに來た時、オーコナーは一緒に晩飯を食べに來るやうに言つた。皆んな澤山御馳走を食ひ、その後で酒を飲んで、船長は醉つた。酒盛りの最中に一本の手紙がオーコナーに來た。それは友達の死んだ通知で、彼は長い旅に出かけなければならなかつた。支度をしてゐると、船長は彼の傍へ來た。

「あなたは奥さんが好きですか?」船長は聞いた。

「好きです。」 オーコナーは答へた。

「あなたが旅に出てゐる間、どんな男も奥さんに近づかなかつたら二十ギニ賭けませんか?」

「賭けませう。」 オーコナーはさう言つて、出かけた。

屋敷の近くの道傍でつまらない物を賣つてゐる婆が居た。オーコナーの夫人は彼女を自分の部屋に上らせ、大きな箱の中で寢ることを許した。船長は道傍の婆の所へ行つた。

「いくら出せばお前の箱の中で一晩私を寢かしてくれるか?」と聞いた。

「いくら貰つてもそんな事は駄目です。」と婆は云つた。

「十ギニ?」

「駄目です。」

「十二ギニ?」

「駄目です。」

「十五ギニ?」

「それならよろしい。」

そこで婆はその金を貰ひ、船長を箱の中に隠した。夜になるとオーコナ一夫人は部屋にはひつて來た。船長が箱の穴から見てゐると、彼女は三つの指環を拔き、それを頭の上の爐棚のやうになつた板の上に置き、それから肌着のほか皆着物を脱いで、床にはひつた。

彼女が寢込んでしまふと、船長は早速箱から出て來て、蠟燭に火を

爺さんは一寸休んだ。すると、話の間に茶の間が一杯になるまで集まつて來てゐた男女の口から救はれた重い溜息が洩れた。

船長が箱から出て來るあたりから、英語を知らないらしい女たちも、糸を紡ぐ手を止めて、その先を聞かうと息を凝らしてゐた。

爺さんは續けた――

オーコナーが歸つて來ると、船長は彼に逢つて、一晩奥さんの部屋にはひつたことがあると云つて、二つの指環を渡した。

オーコナーは賭の二十ギニを出した。それから屋敷へ上つて、窓から荒海を眺めようと妻を連れ出し、眺めてゐる間に彼女を後から突くと、彼女は崖の上から海の中へ落ちた。

一人のお婆さんが岸に居て、落ちるのを見てゐた。波の中にはひつて行き、づぶぬれになり狂人のやうになつてゐる夫人を引き上げ、濡れた着物を脱がせ、自分の襤褸を着せた。

オーコナーは妻を窓から突き落すと、陸の方へ逃げた。

暫くして夫人はオーコナーを探しに出かけ、国中を長い間あちこち歩いてゐるうち、彼は畑で六十人の人たちと一緒に刈入れをしてゐると云ふ噂を耳にした。

彼女はその畑にやつて來て、はひらうとしたが門番が門を開けてくれない。その時、畑の持主が通りかかつたので、譯を話して中にはひつた。彼女の夫は其處で刈入れをしてゐたが、彼女を知らないのか、目もくれない。そこで持主に夫を教へて、出して貰ひ、一緒に出かけた。

夫人は馬の居る道へ連れて來て、二人は馬に騎つて立ち去つた。

オーコナーが嘗つて小男に逢つた處へ来ると、その男が目の前に居た。

「私の金を持つて來たのか?」その男が聞く。

「さうぢやありません。」 オーコナーは答へた。

「そんなら、お前の身體の肉を切り取つて、支拂つて貰ひたい」と云ふ。

皆んな家の中にはひると、ナイフが出され、白い綺麗な布がテーブルに敷かれ、オーコナーはその布の上に寢かされた。

そこで小男が小槍で將に突き刺さうとした時、オーコナ一夫人は云つた。

「肉を五ポンド取ると、あなたは約束したのですか?」

「その通りだ。」

「血の

「いや、血は。」と男は云つた。

「肉は切り取つてもよござんす。」オーコナー夫人は云つた。

「併し、一滴たりとも血を流したら、私はあなたをこれで撃ち殺します。」 さういつて夫人はピストルを男の顏へつきつけた。

小男は逃げて行き、それきり行方がわからなかつた。

二人は屋敷へ歸ると、大宴會を開き、船長や婆や、オーコナー夫人を海から引き上げた婆さんを招待した。

皆んな充分食べてしまふと、先づオーコナー夫人は銘銘の物語をしてくれと云つた。さうして彼女は海から救はれた事、夫を見付けた事を語つた。

するとお婆さんは、濡れて狂人のやうになつてゐるオーコナー夫人を見付けて家に連れ歸り、自分の襤褸を着せた話をした。

夫人は船長に話をしてくれと願つたが、彼はどうしても話したくないと云つた。すると彼女はポケットからピストルを出してテーブルの端に置き、自分の話をしない者は撃つぞと云つた。

そこで船長は、箱の中にはひり、彼女には少しも手を觸れずに寢臺の所まで行つて、指環を盗んだ次第を物語つた。

すると婦人はピストルを取つて婆を撃ち貫き、崖の上から海の中へ抛り込んだ。

それでおしまひ。

此の大西洋の濕つた岩に住んでゐる文盲の人の口から歐洲的な聯想の豐かな物語を聞くのは、不思議な感じを私に起させた。

此の貞淑な妻の話は、我我をシムベリン〔沙翁の劇の名〕を通り越して、アルノ河の陽光のほとりに誘ひ、フロレンスから愛の物語をしに出かける陽氣な人達の處へつれて行く。また我我をマイン河畔ブュールツブルヒの低い葡萄棚へつれて行く。其處は中世に、「ルブレヒト・フォン・ヴュールツブルヒ作の二人の商人と貞淑な妻」といふ同じやうな物語が語られた處である。

今一つの肉五ポンドに関する部分はペルシアとエヂプトから「ジュスタ・ロマノルム」の物語やフロレンスの公證人なるセル・ヂォヴァンニの「小説ペコローネ」へかけて今でも廣く流布されてゐる。

此の二つの話の現在一つに合體した物は既にゲール族の中にある。またキャンベルの「西部ハイランドの民間説話」の中にも稍々それに似た話がある。

*

There were two farmers in County Clare. One had a son, and the other, a fine rich man, had a daughter.

The young man was wishing to marry the girl, and his father told him to try and get her if he thought well, though a power of gold would be wanting to get the like of her.

'I will try,' said the young man.

He put all his gold into a bag. Then he went over to the other farm, and threw in the gold in front of him.

'Is that all gold?' said the father of the girl.

'All gold,' said O'Conor (the young man's name was O'Conor).

'It will not weigh down my daughter,' said the father.

'We'll see that,' said O'Conor.

Then they put them in the scales, the daughter in one side and the gold in the other. The girl went down against the ground, so O'Conor took his bag and went out on the road.

As he was going along he came to where there was a little man, and he standing with his back against the wall.

'Where are you going with the bag?' said the little man. 'Going home,' said O'Conor.

"Is it gold you might be wanting?' said the man. 'It is, surely,' said O'Conor.

'I'll give you what you are wanting,' said the man, 'and we can bargain in this way--you'll pay me back in a year the gold I give you, or you'll pay me with five pounds cut off your own flesh.'

That bargain was made between them. The man gave a bag of gold to O'Conor, and he went back with it, and was married to the young woman.

They were rich people, and he built her a grand castle on the cliffs of Clare, with a window that looked out straight over the wild ocean.

One day when he went up with his wife to look out over the wild ocean, he saw a ship coming in on the rocks, and no sails on her at all. She was wrecked on the rocks, and it was tea that was in her, and fine silk.

O'Conor and his wife went down to look at the wreck, and when the lady O'Conor saw the silk she said she wished a dress of it.

They got the silk from the sailors, and when the Captain came up to get the money for it, O'Conor asked him to come again and take his dinner with them. They had a grand dinner, and they drank after it, and the Captain was tipsy. While they were still drinking, a letter came to O'Conor, and it was in the letter that a friend of his was dead, and that he would have to go away on a long journey. As he was getting ready the Captain came to him.

'Are you fond of your wife?' said the Captain.

'I am fond of her,' said O'Conor.

'Will you make me a bet of twenty guineas no man comes near her while you'll be away on the journey?' said the Captain.

'I will bet it,' said O'Conor; and he went away.

There was an old hag who sold small things on the road near the castle, and the lady O'Conor allowed her to sleep up in her room in a big box. The Captain went down on the road to the old hag.

'For how much will you let me sleep one night in your box?' said the Captain.

'For no money at all would I do such a thing,' said the hag.

'For ten guineas?' said the Captain.

'Not for ten guineas,' said the hag.

'For twelve guineas?' said the Captain.

'Not for twelve guineas,' said the hag.

'For fifteen guineas?' said the Captain.

'For fifteen I will do it,' said the hag.

Then she took him up and hid him in the box. When night came the lady O'Conor walked up into her room, and the Captain watched her through a hole that was in the box. He saw her take off her two rings and put them on a kind of a board that was over her head like a chimney-piece, and take off her clothes, except her shift, and go up into her bed.

As soon as she was asleep the Captain came out of his box, and he had some means of making a light, for he lit the candle. He went over to the bed where she was sleeping without disturbing her at all, or doing any bad thing, and he took the two rings off the board, and blew out the light, and went down again into the box.

He paused for a moment, and a deep sigh of relief rose from the men and women who had crowded in while the story was going on, till the kitchen was filled with people.

As the Captain was coming out of his box the girls, who had appeared to know no English, stopped their spinning and held their breath with expectation.

The old man went on--

When O'Conor came back the Captain met him, and told him that he had been a night in his wife's room, and gave him the two rings. O'Conor gave him the twenty guineas of the bet. Then he went up into the castle, and he took his wife up to look out of the window over the wild ocean. While she was looking he pushed her from behind, and she fell down over the cliff into the sea.

An old woman was on the shore, and she saw her falling. She went down then to the surf and pulled her out all wet and in great disorder, and she took the wet clothes off her, and put on some old rags belonging to herself.

When O'Conor had pushed his wife from the window he went away into the land.

After a while the lady O'Conor went out searching for him, and when she had gone here and there a long time in the country, she heard that he was reaping in a field with sixty men.

She came to the field and she wanted to go in, but the gate-man would not open the gate for her. Then the owner came by, and she told him her story. He brought her in, and her husband was there, reaping, but he never gave any sign of knowing her. She showed him to the owner, and he made the man come out and go with his wife.

Then the lady O'Conor took him out on the road where there were horses, and they rode away.

When they came to the place where O'Conor had met the little man, he was there on the road before them.

'Have you my gold on you?' said the man.

'I have not,' said O'Conor.

'Then you'll pay me the flesh off your body,' said the man. They went into a house, and a knife was brought, and a clean white cloth was put on the table, and O'Conor was put upon the cloth.

Then the little man was going to strike the lancet into him, when says lady O'Conor--

'Have you bargained for five pounds of flesh?'

'For five pounds of flesh,' said the man.

'Have you bargained for any drop of his blood?' said lady O'Conor.

'For no blood,' said the man.

'Cut out the flesh,' said lady O'Conor, 'but if you spill one drop of his blood I'll put that through you.' And she put a pistol to his head.

The little man went away and they saw no more of him.

When they got home to their castle they made a great supper, and they invited the Captain and the old hag, and the old woman that had pulled the lady O'Conor out of the sea.

After they had eaten well the lady O'Conor began, and she said they would all tell their stories. Then she told how she had been saved from the sea, and how she had found her husband.

Then the old woman told her story; the way she had found the lady O'Conor wet, and in great disorder, and had brought her in and put on her some old rags of her own.

The lady O'Conor asked the Captain for his story; but he said they would get no story from him. Then she took her pistol out of her pocket, and she put it on the edge of the table, and she said that any one that would not tell his story would get a bullet into him.

Then the Captain told the way he had got into the box, and come over to her bed without touching her at all, and had taken away the rings.

Then the lady O'Conor took the pistol and shot the hag through the body, and they threw her over the cliff into the sea.

That is my story.

It gave me a strange feeling of wonder to hear this illiterate native of a wet rock in the Atlantic telling a story that is so full of European associations.

The incident of the faithful wife takes us beyond Cymbeline to the sunshine on the Arno, and the gay company who went out from Florence to tell narratives of love. It takes us again to the low vineyards of Wurzburg on the Main, where the same tale was told in the middle ages, of the 'Two Merchants and the Faithful Wife of Ruprecht von Wurzburg.'

The other portion, dealing with the pound of flesh, has a still wider distribution, reaching from Persia and Egypt to the Gesta Rornanorum, and the Pecorone of Ser Giovanni, a Florentine notary.

The present union of the two tales has already been found among the Gaels, and there is a somewhat similar version in Campbell's Popular Tales of the Western Highlands.

[やぶちゃん注:「クレア郡」“County Clare”。アイルランドのクレア州。アラン諸島を望むゴールウェイ湾南の本土、マンスター地方の州名。

「オーコナーの夫人は彼女を自分の部屋に上らせ、大きな箱の中で寢ることを許した。」原文は“and the lady O'Conor allowed her to sleep up in her room in a big box.”であるが、気になるのは、この訳ではこの夫が長の留守をすることとなった時点で「許した」と読めてしまうことである。しかし、これは、そうした雑貨商を営む身寄りのない老婆を可哀相に思って、以前からオーコナー夫人は、夜は彼女の部屋の大きな櫃を寝床にすることを許していた、という風に読まないとおかしいように思われる。栩木伸明氏訳「アラン島」でもそのように訳されてある。

「爐棚のやうになつた板の上」原文は“on a kind of a board that was over her head like a chimney-piece”。“chimney-piece”は“mantelpiece”マントルピース、暖炉のことだから、如何にも迂遠な表現である。これは実際にはマントルピースではなく、それに似たような形状の当時の特殊な部屋装飾であることをパット爺さんは暗に言わんとしているように思われる。

「船長が箱から出て來るあたりから、英語を知らないらしい女たちも、糸を紡ぐ手を止めて、その先を聞かうと息を凝らしてゐた。」は“As the Captain was coming out of his box the girls, who had appeared to know no English, stopped their spinning and held their breath with expectation.”であるが、「英語を知らないらしい女たち」が「ほつとし」「息を凝らして」「その先を聞かうと」していたというのは訳としては不自然である。“had appeared to know no English”は、そのちょっと前にシングが話しかけても、『英語はまるで分からないかのような素振りを見せていた女たちも』、の意であろう。突然やって来た若き異邦人シングへの、素朴なアランの女たちの、そのはにかみが伝わってくるシーンだ。

「陸の方へ逃げた。」原文の“he went away into the land.”を逐語的に訳してはいるが、如何か? 妻に裏切られたと思った失意と絶望によって自暴自棄となったオーコナーは、衝動的に『内陸の奥の方へと、彷徨い出でて、城を去ってしまった。』と訳したいところである。

「彼女を知らないのか、目もくれない。」原文“but he never gave any sign of knowing her.”。「彼女を知らないのか」では、日本語としては、単純な仮定疑問文として、本当に彼女のことをもう忘れてしまっているのか、という意味にも(寧ろ積極的にそのように)とれてしまう。そうではあるまい。ここは寧ろ、彼女が裏切ったと信じ込んで絶望し、やけのやんぱちで一介の雇われの農奴に身をやつしてしまっているから、『しかし彼は、彼女のことを知っているというこれっぽちの素振りをもいっかな見せずにいる』という意味であろう。

「シムベリン」“Cymbeline”は古ケルト時代のブリテン王シンベリンの娘イモージェン“Imogen”と愛人ポステュマス“Posthumus”に纏わるシェイクスピアの戯曲。1611年頃には上演されたと推測されている。作中、シンベリンによってイモージェンと引き裂かれて追放されたポステュマスはイタリアに行き(本文の「アルノ河」や「フロレンス」(=フィレンツェ)というイタリア風の陽気な喜劇コンセプトへのシングの連想展開は、このシーンに引っ掛けてあるものと思われる)、そこで知り逢ったヤーキモーなる人物とイモージェンの貞節について賭けをする。ヤーキモーはブリテンに向かうと大きな鞄の中に潜んでイモージェンの部屋に侵入、秘かにイモージェンの胸の痣と部屋の造作とを偸み見てイタリアに帰還すると、ポステュマスにイモージェンを美事に落としたと嘘をつく。絶望したポステュマスはブリテンに残してきた下男にイモージェン殺害を命ずるという、本話前半部と極めて類似したシーンがある(本注はウィキの「シンベリン」を参考にした)。

「マイン河畔ブュールツブルヒ」“Wurzburg on the Main”後の中世伝承譚の方は「ルブレヒト・フォン・ヴュールツブルヒ作の二人の商人と貞淑な妻」“'Two Merchants and the Faithful Wife of Ruprecht von Wurzburg.'”と訳されているから「ブュールツブルヒ」は「ヴュールツブルヒ」の誤植であろう。現在はヴュルツブルクと表記される。

「ジュスタ・ロマノルム」“Gesta Rornanorum”は13世紀から14世紀にかけて編纂されたラテン語民話集。Charles Swan

英訳本(安川晃他編注)「ゲスタ・ロマノールム Gesta Romanorum ローマ人達の行状記」が1992年に弓プレスから出版されている。

『フロレンスの公證人なるセル・ヂォヴァンニの「小説ペコローネ」』原文“the Pecorone of Ser Giovanni, a Florentine notary.”。中世イタリアのジョヴァンニ・フィオレンティーノ“Giovanni Fiorentino”(“ser”が頭につくが“Fiorentino”自体が「フィレンツェの」の意であり、何らかの冠称のようである)が書いた「デカメロン」風の物語集“Il Pecorone”「イル・ペコローネ」(「愚か者」の意)。前の「ゲスタ・ロマノールム」とともに、シェイクスピアの「ヴェニスの商人」の種本とされており、その四日目第一話に本話と共通した例の人肉の裁きの話が載る。

『キャンベルの「西部ハイランドの民間説話」』ケルト民俗学の権威であったJohn Francis Campbell(1821年~1885年)が1860年から1862年にかけて刊行した民間説話集。ゲール語からの翻訳採録。]

マイケルと外出すると、後からついて行けないほど足が早いので、石灰岩に多くある端の尖つた風化石で靴をズタズタにしてしまふ。

宿の人たちは昨夜それに就いて相談して、結局一足の革草鞋を私に作つてくれる事になつた。それを今日は岩の中で履いてゐる。

それは生の牛の革から出來ただけの物で、外側に毛があり、釣糸の両端を以つて爪先の上と踵の周りとで編み合はされ、糸はぐるつと廻つて足の甲の上で結ばれてある。

夜脱いだ時は、それを水桶の中に入れておく。革を硬いままにしておくと足や靴下を切るからである。同じ理由で、足を常に

初め私は、長靴を履く時に自然にするやうに、踵に身體の重みをかけて、かなり傷をした。併し、数時間後には普通の歩き方を覺えて、島の何處へでも案内人について行けるやうになつた。

北の方の、崖下の或る處では、殆んど一哩近くも普通の歩き方では一歩も歩けず、岩から岩へ飛び歩くのである。此處でも私は爪先を自然に使ふのがわかつた。と云ふのは、行手のどんな小さな穴へでも、一生懸命に足先でしがみついて跳ぶことがわかつたからである。そして餘り緊張した爲に足の筋肉全體が痛んだ。

歐洲にある重い長靴の無い事が此島の人たちに野獸のやうな素早い歩き方を保存させ、また一方に於て、彼等の一般的に簡素な生活は肉體上の他のいろいろな點に於いて完成を與へた。彼等の生活の樣式は、その四圍に住んでゐる動物の巣や穴より以上に手の込んだ物に從つて営まれてゐるのでなく、或る意味に於いて、彼等は、野生の馬が駄馬や馬車馬よりは寧ろ完全に育てられた馬に似てゐると同じやうに、勞働者や職人よりは――我我の上流の比較的立派な型に――自然の理想に適ふまでに手をかけて育てられた人人に近いやうに見えるる、これと同じやうな自然發達の種族は、恐らく半ば文化の開けた國に珍らしくないのである。併し此處では、野生的動物の性質の中に際立つて、古代社會の純良な物の片影が交つてゐる。

私がマイケルと散歩してゐる間に、屢々時間を聞きに來る者がある。しかし、さういつた人達は時刻といふ物の約束をぼんやりと理解する以上に充分近代的の時間といふものに慣れてゐない。

私の時計では何時と云つても承知せず、日暮れまでどの位あるかと聞く。

此の島で甚だ妙な事は、一般に時間は風の方向と関係してゐると思つてゐる。殆んどどの家もそんな風に建てられ、向き合つて二つの戸があり、風の當らない方の戸は、家の中に明りを採る爲に一日中開いたままになつてゐる。風が北から吹けば南の戸が開いて居り、茶の間の床の上を戸柱の蔭が横に動いて行くので、時間がわかる。ところが、風が南に變ると、直ぐに北の方の戸があいて、簡單な日時計を作る事さへ知らない人たちは困惑する。

此の戸口の仕組はまた今一つの面白い結果を生ずる。村の往來の片側は、どこの戸口も開いたままになつて、女たちが敷居の上に腰かけたりしてゐるのに、他の方の側の戸口は皆しまつて、人の住んでゐる気配も見えない事がよくある。風が變ると、その瞬間に凡ての物が反對になつてしまふ。一時間の散歩の後歸つてみると、何もかも道の片側から他の側へ移り變つてゐるやうな事が屢々ある。

此の家では戸口が變ると茶の間の樣子ががらつと變つて、庭や小路の眺められる輝かしいまで明るい茶の間は、雄大な海を見わたす薄暗い穴倉のやうになる。

北風の吹く日には、お婆さんはどうにか時間通りに私の食事を作るが、さうでない日には六時のお茶を三時に作る事がある。それを斷はると、三時間も炭火にとろとろ煮て、また六時になつて、充分温かいかどうかを非常に心配しながら持つて來る。

爺さんは、私が去る時には時計を送つてもらひたいと云ふ。私の贈つた物が何か家の中にあると、私のことを忘れないだらうし、時計は他の物のやうに重寶ではなくとも、それを見ればいつでも私を想ひ出すだらう、と彼は云ふ。

一般に正確な時刻を知らない爲に、人人は規則正しい食事をする事が出來ない。

家の人は晩は一緒に食事をするらしい。また時には朝も、夜明け少し後、皆が仕事に思ひ思ひに出かける前に一緒に食事をする事がある。併し晝間は、腹がすけばいつでも、ただ茶を一杯飲んだり、パンを一片食つたり、或ひは芋を食べたりするだけである。

外で働いてゐる者は不思議にあまり食べない。マイケルは時時何も食べないで八九時間も芋畑の草取りをして、外にゐる事がある。歸つて來て手製のパンの幾片かを食べるが、それでいつ誘つても私と一緒に出かけて、島を何時間でも歩き廻るやうに用意が出來てゐる。

彼等は鹽豚・鹽肴のほかには動物質の食物は取らない。お婆さんは生の肉を食べると、大病になると云ふ。

茶や砂糖や小麥が一般に用ひられるやうになつたのは數年前からの事で、その前は鹽肴が今日より以上に食事の重要品であつた。それで皮膚病が、今は此の島にも少くなつたが、以前には隨分多かつたさうである。

*

Michael walks so fast when I am out with him that I cannot pick my steps, and the sharp-edged fossils which abound in the limestone have cut my shoes to pieces.

The family held a consultation on them last night, and in the end it was decided to make me a pair of pampooties, which I have been wearing to-day among the rocks.

They consist simply of a piece of raw cowskin, with the hair outside, laced over the toe and round the heel with two ends of fishing-line that work round and are tied above the instep.

In the evening, when they are taken off, they are placed in a basin of water, as the rough hide cuts the foot and stocking if it is allowed to harden. For the same reason the people often step into the surf during the day, so that their feet are continually moist.

At first I threw my weight upon my heels, as one does naturally in a boot, and was a good deal bruised, but after a few hours I learned the natural walk of man, and could follow my guide in any portion of the island.

In one district below the cliffs, towards the north, one goes for nearly a mile jumping from one rock to another without a single ordinary step; and here I realized that toes have a natural use, for I found myself jumping towards any tiny crevice in the rock before me, and clinging with an eager grip in which all the muscles of my feet ached from their exertion.

The absence of the heavy boot of Europe has preserved to these people the agile walk of the wild animal, while the general simplicity of their lives has given them many other points of physical perfection. Their way of life has never been acted on by anything much more artificial than the nests and burrows of the creatures that live round them, and they seem, in a certain sense, to approach more nearly to the finer types of our aristocracies--who are bred artificially to a natural ideal--than to the labourer or citizen, as the wild horse resembles the thoroughbred rather than the hack or cart-horse. Tribes of the same natural development are, perhaps, frequent in half-civilized countries, but here a touch of the refinement of old societies is blended, with singular effect, among the qualities of the wild animal.

While I am walking with Michael some one often comes to me to ask the time of day. Few of the people, however, are sufficiently used to modern time to understand in more than a vague way the convention of the hours, and when I tell them what o'clock it is by my watch they are not satisfied, and ask how long is left them before the twilight.

The general knowledge of time on the island depends, curiously enough, on the direction of the wind. Nearly all the cottages are built, like this one, with two doors opposite each other, the more sheltered of which lies open all day to give light to the interior. If the wind is northerly the south door is opened, and the shadow of the door-post moving across the kitchen floor indicates the hour; as soon, however, as the wind changes to the south the other door is opened, and the people, who never think of putting up a primitive dial, are at a loss.

This system of doorways has another curious result. It usually happens that all the doors on one side of the village pathway are lying open with women sitting about on the thresholds, while on the other side the doors are shut and there is no sign of life. The moment the wind changes everything is reversed, and sometimes when I come back to the village after an hour's walk there seems to have been a general flight from one side of the way to the other.

In my own cottage the change of the doors alters the whole tone of the kitchen, turning it from a brilliantly-lighted room looking out on a yard and laneway to a sombre cell with a superb view of the sea.

When the wind is from the north the old woman manages my meals with fair regularity; but on the other days she often makes my tea at three o'clock instead of six. If I refuse it she puts it down to simmer for three hours in the turf, and then brings it in at six o'clock full of anxiety to know if it is warm enough.

The old man is suggesting that I should send him a clock when I go away. He'd like to have something from me in the house, he says, the way they wouldn't forget me, and wouldn't a clock be as handy as another thing, and they'd be thinking of me whenever they'd look on its face.

The general ignorance of any precise hours in the day makes it impossible for the people to have regular meals.

They seem to eat together in the evening, and sometimes in the morning, a little after dawn, before they scatter for their work, but during the day they simply drink a cup of tea and eat a piece of bread, or some potatoes, whenever they are hungry.

For men who live in the open air they eat strangely little. Often when Michael has been out weeding potatoes for eight or nine hours without food, he comes in and eats a few slices of home-made bread, and then he is ready to go out with me and wander for hours about the island.

They use no animal food except a little bacon and salt fish. The old woman says she would be very ill if she ate fresh meat.

Some years ago, before tea, sugar, and flour had come into general use, salt fish was much more the staple article of diet than at present, and, I am told, skin diseases were very common, though they are now rare on the islands.

[やぶちゃん注:「完全に育てられた馬」原文“thoroughbred”。言うまでもなく、英国原産種にアラビア馬その他を交配して改良・育成した競走馬のことで、現代ではそのまま「サラブレッド」と訳した方がすんなり意味が落ちる。

「彼等の生活の樣式は、その四圍に住んでゐる動物の巣や穴より以上に手の込んだ物に從つて営まれてゐるのでなく」及び「しかし、さういつた人達は時刻といふ物の約束をぼんやりと理解する以上に充分近代的の時間といふものに慣れてゐない。」の訳語は「以上に」の部分を「以上には」とした方が今の日本語としては分かりよい。則ち、『彼らの生活の様式は自然界の動物の本能的な営巣に従っており、それ以上の、我々が言うところの「近代的な知性」によって営まれた「文明的生活」とは無縁で』、『彼らの時間概念は一日の大まかな自然現象としての変化をぼんやりと理解する程度のものであって、それ以上の、我々が言うところの「近代的な概念」によって縛られた「絶対的時間」には慣れていない』のである、と言っているのである。

「さうでない日には六時のお茶を三時に作る事がある。」原文は“she often makes my tea at three o'clock instead of six.”で確かに“tea”であるが、これは前文で“my meals”を「食事」と訳しており、それを受けての文であるから、これはお婆さんの作る(失礼ながら)大したことのない粗末な「夕食」が、所謂、イングランドの習慣である午後五時頃に紅茶とともに摂る、ディナーを事前に補うところの軽食“afternoon[five-o'clock]tea”(夕食が軽い場合には肉料理附きで“high[meat]tea”と言う)のように感ぜられたことからの“tea”なのではなかろうか。訳としては夕餉をでいいのではないか? 但し、もしかすると実際にこのお婆さんは“afternoon tea”の後、ちゃんとディナーかサパーを出していたのかも知れない。お婆さんの名誉のために附言しておく。

「爺さん」ここまで登場していなかったが、これはどうもシングが泊まっているこの屋の主、「お婆さん」の夫と思われる。]

[フッカーの船主]

此の灰色の雲と海の間で幾週間か暮した事のない者には、女の赤い着物が、殊に今朝のやうにたくさん群がつてゐるのを目に止める樂しさはわからないであらう。

若い牛が、近日中に開かれる本土の市場へ船積される筈だと聞いた。それで夜明け少し前、私はそれを見ようと波止揚へ下りて行つた。

灣は催してゐる雨氣に灰色に蔽はれてゐたが、雲の、うすさに海の上には銀のやうな明るさがあり、コニマラの山山には常ならぬ靑さが濃かつた。

私が砂山を越えて行くと、灰色の帆をかけた漁船が滑るやうに靜かに漕ぎ出して行つたり、また波止場へ向つて進んで來たりしてゐた。赤毛の牛の群が、岩と海の境目にある緣の長い草の道でもつて目新しい色の調和を作りながら、大概は女に追はれて方方から集まつて來つつあつた。

波止場その物も牡牛と大勢の人で混み合つてゐた。群集の中にあたりの者たちに威張つてゐるらしい普通の人とは違つた一人の娘が居た。彼女の妙な恰好をした鼻柱や狭い頰は妖精のやうな顏を思はせたが、髮の毛と皮膚の美しさは獨特の魅力であつた。

屋根のない船艙に若い牛を立たせ得るだけぎつしり詰めると、持主は女房や姉妹たちと甲板に飛び下りて出發し初めた。此の女房や姉妹たちは、ゴルウェーで男達の濫費を防ぐ爲に附いて行くのである。直ぐその後で、老いぼれてヨロヨロした一般の漁船がコニマラから泥炭を積んで波止場の方へやつて來た。荷卸をやつてゐる間に、男達がすつかり波止場の緣に腰かけて、持主が怒つて氣が荒くなるまでに木材の腐つてゐる事をとやかく云つた。

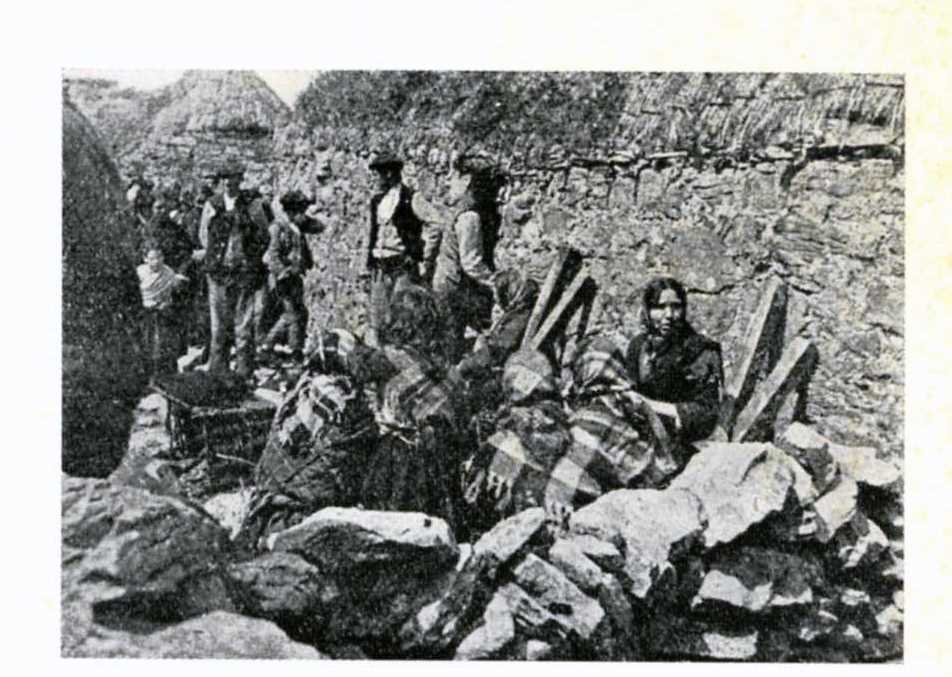

さてボートが波止場に來られなくなつた程汐が退いたので、場所を東南の細長い砂地に移し、其處で殘りの牛は寄波の中を船へ積み込まれた。漁船は岸から八十ヤードぐらゐの所に碇泊し、カラハが牛を引張つて漕ぎ去り漕ぎ戻つた。各々の牡牛は順順に捕へられ、革の吊帶を體に廻はされた。その吊帶で牛は船の上に引き揚げられるのである。今一つの綱が角に結ばれて、カラハの艫にゐる人に渡される。それから年は寄波の中へ無理に下ろされ、餘り長く苦しませないやうにして波の深みから出された。少し泳ぐやうになると、漁船の方へ牽いて行き、半ば溺れた狀態で船の中へ引き揚げられた。

砂地では自由がきくので、激しい反抗心を起すらしく、中には危險な取組を冒してやつと捕へられる牛もあつた。最初の一遍で成功するとは限らず、私は三歳の牛が角で二人の男をつり上げ、もう一人を角で五十ヤードも砂地を引きずつて、やつと鎭められたのを見た。

こんな仕事のなされてゐる間中、お内儀さんたちや子供たちの群は岸の緣に集まつて、ひやかしとも賞讃ともつかない事を叫び續ける。

家に歸つてみると、此處のお婆さんの娘も本土へ行つた女の一人で、その九ケ月位の赤ん坊はお婆さんに預けられてあつた。

はひつて行くと、お婆さんは晩飯の用意に忙しく、此の時間にいつもやつて來るパット・ディレイン爺さんが搖加藍を搖つてゐた。その搖藍はみすぼらしい柳細工で、下に

此の家にゐるもう一人の娘もまた市に行つたので、お婆さんが私と赤ん坊の兩人、おまけに爐邊の穴にゐる一群のひよこまでも世話をしなければならなくなつた。茶を賴んだ時や、お婆さんが水汲みに行つた時は、私が搖藍をゆすぶる番になつた。

*

No one who has not lived for weeks among these grey clouds and seas can realise the joy with which the eye rests on the red dresses of the women, especially when a number of them are to be found together, as happened early this morning.

I heard that the young cattle were to be shipped for a fair on the mainland, which is to take place in a few days, and I went down on the pier, a little after dawn, to watch them.

The bay was shrouded in the greys of coming rain, yet the thinness of the cloud threw a silvery light on the sea, and an unusual depth of blue to the mountains of Connemara.

As I was going across the sandhills one dun-sailed hooker glided slowly out to begin her voyage, and another beat up to the pier. Troops of red cattle, driven mostly by the women, were coming up from several directions, forming, with the green of the long tract of grass that separates the sea from the rocks, a new unity of colour.

The pier itself was crowded with bullocks and a great number of the people. I noticed one extraordinary girl in the throng who seemed to exert an authority on all who came near her. Her curiously-formed nostrils and narrow chin gave her a witch-like expression, yet the beauty of her hair and skin made her singularly attractive.

When the empty hooker was made fast its deck was still many feet below the level of the pier, so the animals were slung down by a rope from the mast-head, with much struggling and confusion. Some of them made wild efforts to escape, nearly carrying their owners with them into the sea, but they were handled with wonderful dexterity, and there was no mishap.

When the open hold was filled with young cattle, packed as tightly as they could stand, the owners with their wives or sisters, who go with them to prevent extravagance in Galway, jumped down on the deck, and the voyage was begun. Immediately afterwards a rickety old hooker beat up with turf from Connemara, and while she was unlading all the men sat along the edge of the pier and made remarks upon the rottenness of her timber till the owners grew wild with rage.

The tide was now too low for more boats to come to the pier, so a move was made to a strip of sand towards the south-east, where the rest of the cattle were shipped through the surf. Here the hooker was anchored about eighty yards from the shore, and a curagh was rowed round to tow out the animals. Each bullock was caught in its turn and girded with a sling of rope by which it could be hoisted on board. Another rope was fastened to the horns and passed out to a man in the stem of the curagh. Then the animal was forced down through the surf and out of its depth before it had much time to struggle. Once fairly swimming, it was towed out to the hooker and dragged on board in a half-drowned condition.

The freedom of the sand seemed to give a stronger spirit of revolt, and some of the animals were only caught after a dangerous struggle. The first attempt was not always successful, and I saw one three-year-old lift two men with his horns, and drag another fifty yards along the sand by his tail before he was subdued.

While this work was going on a crowd of girls and women collected on the edge of the cliff and kept shouting down a confused babble of satire and praise.

When I came back to the cottage I found that among the women who had gone to the mainland was a daughter of the old woman's, and that her baby of about nine months had been left in the care of its grandmother.

As I came in she was busy getting ready my dinner, and old Pat Dirane, who usually comes at this hour, was rocking the cradle. It is made of clumsy wicker-work, with two pieces of rough wood fastened underneath to serve as rockers, and all the time I am in my room I can hear it bumping on the floor with extraordinary violence. When the baby is awake it sprawls on the floor, and the old woman sings it a variety of inarticulate lullabies that have much musical charm.

Another daughter, who lives at home, has gone to the fair also, so the old woman has both the baby and myself to take care of as well as a crowd of chickens that live in a hole beside the fire, Often when I want tea, or when the old woman goes for water, I have to take my own turn at rocking the cradle.

此の島の

幸ひなことには天氣がよいので、日向で日を暮す事が出來る。此の石垣の頂から見渡すと、殆んど四方の海が見え、北と南の方は遙かに延びて遠い山脈へ續く。私の足下、東の方には島の人家のある一つの區域が見え、其處には赤い色の人影が小屋の邊をうろついてゐて、時時、きれぎれに話聲や古い島の歌が聞こえて來る。

*

One of the largest Duns, or pagan forts, on the islands, is within a stone's throw of my cottage, and I often stroll up there after a dinner of eggs or salt pork, to smoke drowsily on the stones. The neighbours know my habit, and not infrequently some one wanders up to ask what news there is in the last paper I have received, or to make inquiries about the American war. If no one comes I prop my book open with stones touched by the Fir-bolgs, and sleep for hours in the delicious warmth of the sun. The last few days I have almost lived on the round walls, for, by some miscalculation, our turf has come to an end, and the fires are kept up with dried cow-dung--a common fuel on the island--the smoke from which filters through into my room and lies in blue layers above my table and bed.

Fortunately the weather is fine, and I can spend my days in the sunshine. When I look round from the top of these walls I can see the sea on nearly every side, stretching away to distant ranges of mountains on the north and south. Underneath me to the east there is the one inhabited district of the island, where I can see red figures moving about the cottages, sending up an occasional fragment of conversation or of old island melodies.

[やぶちゃん注:「

赤ん坊は齒が生えつつあるので、此の數日間、泣いてゐる。母が市に行つたので牛乳で養はれ、時時それが酸つぱかつたり、餘計に飲まされたりするらしい。

併し今朝は大へん機嫌が惡かつたので、家の人たちは村に乳母を探しにやり、間もなく東の方へ少し行つた處に住んでゐる若い女が來て、赤ん坊に天然の食物をまたやるやうになつた。

それから數時間たつて、私はパット爺さんと話さうと思つて茶の間にはひつて行くと、また違つた女が同じやうな親切な役を務めてゐたが、今度は妙にむづかしい顏をした女であつた。

パット爺さんは一人の不貞な妻の話をした。それはこれから述べるが、その後でその女と道德上の口論を初めた。話を聞きにやつて來た若者たちはそれを面白がつて聞いてゐたが、生憎ゲール語で早口に言はれたので、私にはその要點の大略さへつかめなかつた。

此の老人はいつも妙に滅入つた口調で自分の病氣の事や自分で近づきつつあるものと感じてゐる死の事などを語るが、北の島のムールティーン爺さんを思ひ出すやうな諧謔を時時弄する。今日、怪奇な二錢人形がお婆さんのゐる近くの床に落ちてゐた。それを爺さんは拾ひ上げ、お婆さんの顏と見較べるやうに眺めた。それからそれをさし上げて、「お内儀さん、こんなものを持ち出したのはお前さんかね?」と云つた。

これからが彼の物語である。――

*

The baby is teething, and has been crying for several days. Since his mother went to the fair they have been feeding him with cow's milk, often slightly sour, and giving him, I think, more than he requires.

This morning, however, he seemed so unwell they sent out to look for a foster-mother in the village, and before long a young woman, who lives a little way to the east, came in and restored him to his natural food.

A few hours later, when I came into the kitchen to talk to old Pat, another woman performed the same kindly office, this time a person with a curiously whimsical expression.

Pat told me a story of an unfaithful wife, which I will give further down, and then broke into a moral dispute with the visitor, which caused immense delight to some young men who had come down to listen to the story. Unfortunately it was carried on so rapidly in Gaelic that I lost most of the points.

This old man talks usually in a mournful tone about his ill-health, and his death, which he feels to be approaching, yet he has occasional touches of humor that remind me of old Mourteen on the north island. To-day a grotesque twopenny doll was lying on the floor near the old woman. He picked it up and examined it as if comparing it with her. Then he held it up: 'Is it you is after bringing that thing into the world,' he said, 'woman of the house?'

Here is the story:--

[やぶちゃん注:「今度は妙にむづかしい顏をした女であつた」原文は“this time a person with a curiously whimsical expression.”。“whimsical”というのは「気まぐれな。むら気のある。酔狂な」が原義で、そこから「変な。妙な。滑稽な。」の意を派生する。この後の不貞な女の話とそこからパット爺さんとこの女が道徳的な議論を展開することを考えると、この女性の印象が「気難しい」感じの顔で、「頑なで保守的な」女性であったとは、私には思われない。寧ろ、普通の若い母親の印象とは違った「気まぐれでむらっ気のある」、「一種独特な雰囲気を持った」顔つきの女であったのではなかったか? 次の話で不貞な女とされる色気のあるタイプに寧ろ属する女性であったからこそ、議論になったとするべきであろう。栩木氏はこの部分を『この女がへんに色っぽい表情をしているのが目についた』と訳されており、私にはこちらの方が如何にも腑に落ちたのであるが、如何?

「怪奇な二錢人形」原文は“grotesque twopenny doll”であるが、後で「お内儀さん、こんなものを持ち出したのはお前さんかね?」という台詞があるからといって、何か意味ありげな宗教的な依代なわけでは毛頭あるまい。赤ん坊のために買ったものであるが、表情や造作が、奇妙で笑いをさそうような、いい加減にデフォルメされたように見える、如何にもな安物の人形であることを言うのであろう。すると、後の「お内儀さん、こんなものを持ち出したのはお前さんかね?」という台詞も、違ったニュアンスで読める。原文は“'Is it you is after bringing that thing into the world,' he said, 'woman of the house?'”である。パット爺さんは「諧謔を時時弄する」のであるから、『「今になって、この世にこんな奴をもたらしちまったのは、あんた」彼は言った、「女将さんかい?」』、即ち、『女将さん、この子は、お前さんが産んじまった哀れな子かね?』という意味であろう。栩木氏も『おや、奥さん、この子はあんたが産んだ子かいな。』と訳しておられる。]

或る日、私はゴルウェーからダブリンへ歩いてゐた。途中で日が暮れて、まだ町まで十哩もあるので、何處か夜を過す處を探してゐた。するとひどく雨が降り出し、私は歩き疲れたので、道の向う側に屋根のない家らしいものが見えたので、壁が雨除けになるだらうと思つて中にはひつた。

一人の死人がテーブルの上に寢てゐて、蠟燭が

「今晩は、お内儀さん」と私は云ふ。

「今晩は、旅の衆。」と女は云ふ。「雨の中にゐないで、おはひりなさい。」

そこでその女は私を中に入れ、亭主に死なれてお通夜をしてゐるところだと云つた。

「だが、お前さん、喉が乾いてゐるでせう。」彼女は云ふ。「客間にいらつしやい。」

そこで私を客間につれて行き――ちよつと立派な家だつた――そしてコップをソーサーに載せ、甘さうな砂糖とパンを添へて、テーブルの上に出した。

お茶がすんだので、私は、死人のゐる茶の間に戻つて來た。彼女はテーブルから立派な新しいパイプにアルコールを一滴垂らして、私にくれた。

「お前さん、」彼女は云ふ。「この人と二人きりになつたら怖かありませんか?」

「ちつとも怖かありませんよ、お内儀さん。」私は云ふ。「死人は何もしやしません。」

すると彼女は亭主の亡くなつた事を近所の人に知らせに行きたいと云つて、出て行き、外から鍵をかけた。

私は煙草を一服吸つて椅子にもたれ、もう一服テーブルから取つて、――さうさう、今あなたがしてゐるやうに――椅子の

「お前さん、怖がらなくてもいいよ。」その死人が云ふ。「私は決して死んでるのぢやないのだ。此處へ來て助け起してくれ、譯を話して上げるから。」

よしとばかり、私は立つて行き、敷布を取つてやつた。すると彼は綺麗なシャツを着て、立派なフランネルのズボンをはいてゐた。

彼は起き上つて、云ふには――

「私は惡い女房を持つたんでね、お前さん。彼奴の振舞を見とどけてくれようと、死んだ眞似をしてるところだ。」

それから女をやつつける爲の二本の手頃な棒切れを取つて來て、それを両脇において、また死んだやうに長長と横になつた。

半時間もたつと彼の妻は歸つて來たが、若い男が一緒に來た。さうしてその男に茶を出し、疲れてゐるだらうから寢室に行つて寢たらよいと云つた。

若者ははひて行き、女は死人の傍に腰掛て見守つてゐた。少したつと彼女は立ち上つて、云ふには、「お前さん、私はちよつと寢室に行つて

すると死人は起ち上つて二本の棒を押つ取り、今一本を私に渡した。私たちがはひつて行くと、女の頭は男の腕にかかへられて寢てゐるのを見た。

死人は棒切れで男に一撃を喰はした。血は迸つて、廊下まではねた。

それでおしまひ。

*

One day I was travelling on foot from Galway to Dublin, and the darkness came on me and I ten miles from the town I was wanting to pass the night in. Then a hard rain began to fall and I was tired walking, so when I saw a sort of a house with no roof on it up against the road, I got in the way the walls would give me shelter.

As I was looking round I saw a light in some trees two perches off, and thinking any sort of a house would be better than where I was, I got over a wall and went up to the house to look in at the window.

I saw a dead man laid on a table, and candles lighted, and a woman watching him. I was frightened when I saw him, but it was raining hard, and I said to myself, if he was dead he couldn't hurt me. Then I knocked on the door and the woman came and opened it.

'Good evening, ma'am,' says I.